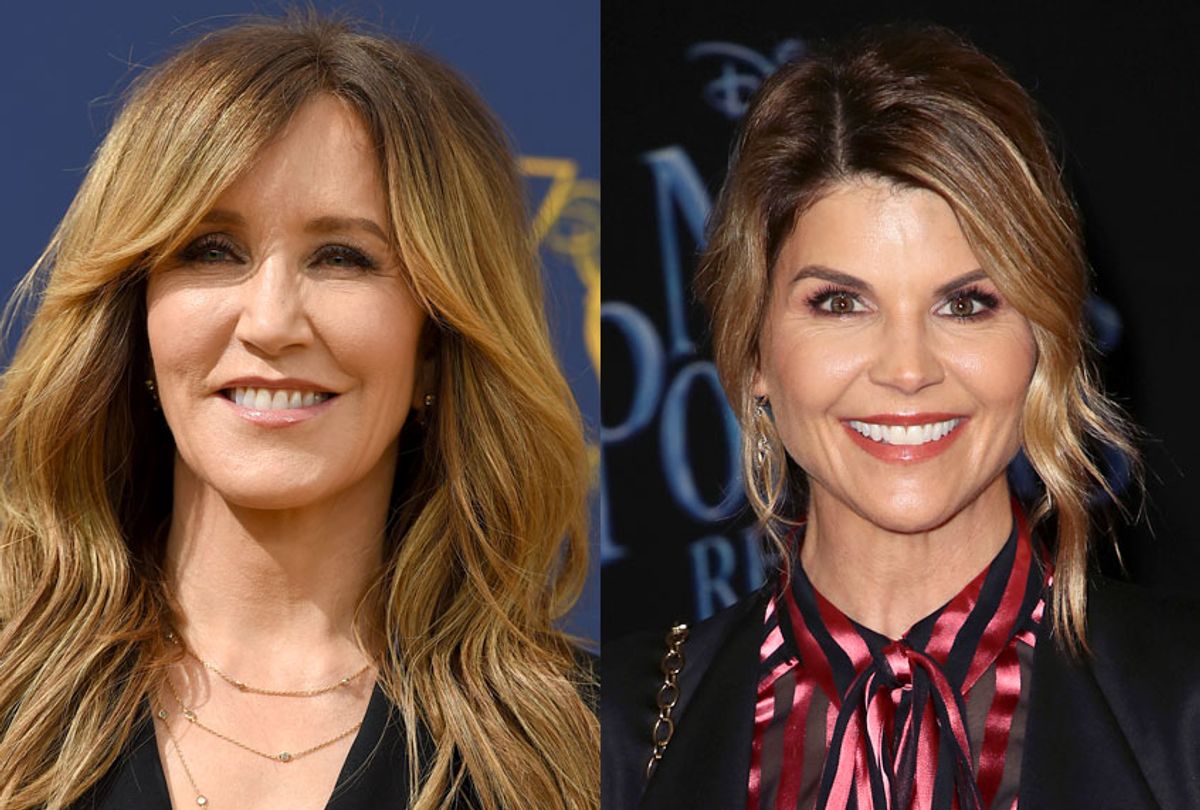

As part of the “Operation Varsity Blues” case that federal prosecutors announced March 12, dozens of people – including Hollywood actresses and wealthy businessmen – stand accused of having bought their children’s way into elite colleges and universities.

As a researcher who has studied how young athletes get admitted to college, I don’t see a major difference between this admission fraud case and how many wealthy families can buy their children’s way into elite colleges through “back” and “side” doors.

In my research, I show how most intercollegiate sports are fed by wildly expensive “pay to play” youth sports pipelines. These pipelines systematically exclude lower income families. It takes money to attend so-called “showcase tournaments” to get in front of recruiters.

In many ways, then, those ensnared in the current criminal case – which alleges that they paid for their children to get spots on the sports teams of big name schools – couldn’t have succeeded if the college admissions process wasn’t already biased toward wealthier families.

Bypassing the front door

Even if college sports is taken out of the equation, the college admissions process already favors wealthy families in a variety of ways.

It has long been known that higher family income usually correlates with higher standardized test scores. There are many test prep companies, including some that guarantee higher scores for approximately US$1,000. Taking advantage of test prep may not be “fraud.” But it certainly provides advantages to the wealthy that have little to do with academic merit.

In his book “The Price of Admission,” Daniel Golden highlights a number of other ways wealthy families can buy their way into elite universities. These include large donations, financing new buildings, creating endowments and playing on parents’ celebrity status. These also have little to do with an applicant’s academic merit, but would never be considered criminal.

Sociologist David Karen has documented how attendance at expensive boarding schools gives wealthy students an admissions advantage to Ivy League universities. That may not be fraudulent, but it certainly seems unfair.

Athletics and admission advantages

So how do the wealthy get an advantage when it comes to college athletics? Research has shown that recruited athletes receive the largest admissions advantages independent of academic merit.

The advantage varies by sport and athletic division, but is almost universal within higher education. Many sports – particularly squash, lacrosse, fencing and rowing – are pricey to play, so rich kids get opportunities that are out of reach for the poor. Even non-elite sports such as soccer and softball are subject to class-based restrictions.

The Mellon Foundation’s report “College and Beyond” found that recruited athletes with lower academic credentials get admitted at four times the rate of non-athletes with similar credentials.

Athlete screening

In the Varsity Blues case, some students’ parents essentially bought their children’s spot on a team. For instance, Stanford sailing coach John Vandemoer is charged with accepting contributions to the sailing program in exchange for recommending two prospective students. He pleaded guilty March 12.

How could a coach pull off this sleight of hand without drawing attention?

The answer, I believe, lies in the growing role of intercollegiate sports in adding some predictability to the very unpredictable enrollment process. Schools want to lock prospective students in as quickly as possible. College athletes are generally admitted through a school’s early decision process. As the proportion of admitted athletes increases, so does the proportion of locked-in applicants.

Colleges also benefit by admitting more students early since those people are not part of acceptance rate calculations. The result is a lower acceptance rate, which inflates the school’s perceived selectivity. This in turn spurs an increase in future applications, which further lowers the acceptance rate – and again increases perceived selectivity – without any objective changes in the actual quality of teaching and research.

College sports teams are an increasingly attractive venue for locking in these early admissions. It is not unusual to have 30 or 40 players on a college soccer or lacrosse team. Most will never play. Women’s crew teams often have more than 100 rowers. Most will never get into a boat. Many will quit the team after one season but remain students.

Of course, because a family can afford to have their child play a sport doesn’t mean the student is a good athlete. The pipeline system is far better at identifying the best payers rather than the best players. Since scholarships are quite rare, it costs colleges almost nothing to have some bad players on the roster. And there are benefits.

I’m certainly not defending the families and entrepreneurs at the heart of the Varsity Blues scandal for breaking the law to take advantage of a system already fraught with inequalities. The prosecutors in this case have insisted that “there can be no separate admissions system for the wealthy.” For that to be true, current practices that favor deep-pocketed families would have to be abandoned. That will require much more than prosecuting a few people who use their wealth to take advantage of an admissions process that already favors the rich.

Rick Eckstein, Professor of Sociology, Villanova University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shares