After the 2016 Democratic National Convention, it’s hard to imagine anyone forgetting the dangers of a hostile and fractious primary. Over the course of that convention, delegates for Sen. Bernie Sanders whipped themselves into an angry frenzy, hyped by conspiracy theories that had been disseminated by Russian intelligence alleging that Hillary Clinton had cheated or the result had been rigged. The result included some Sanders delegates booing everyone on stage — including Sanders himself — who dared suggest that it was important to vote for Hillary Clinton in November.

At the time, Sanders himself seemed shaken by the realization that the ugliness of the primary had gotten so out of control that it might lead to Donald Trump winning the election.

“I caught a glimpse of the fear on [Sanders] face when it became clear his attempt to get everyone ‘Ready for Hillary’ had failed,” Robert Evans of Cracked wrote during the convention, arguing that Sanders was just realizing that his own supporters “seemed willing to elect a human grease fire because their favorite guy lost.”

Most of Sanders’ primary voters, to be clear, voted for Clinton in the general election. Just enough were willing to throw the election to Trump that they arguably played a role in the outcome. About 12 percent of Sanders voters switched to Trump in November, apparently more focused on sticking it to Clinton than on saving the nation. Another group of embittered Sanders supporters, egged on by celebrities like Susan Sarandon and Rosario Dawson, voted for Green Party grifter Jill Stein by wide enough margins to let Trump eke out narrow wins in states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

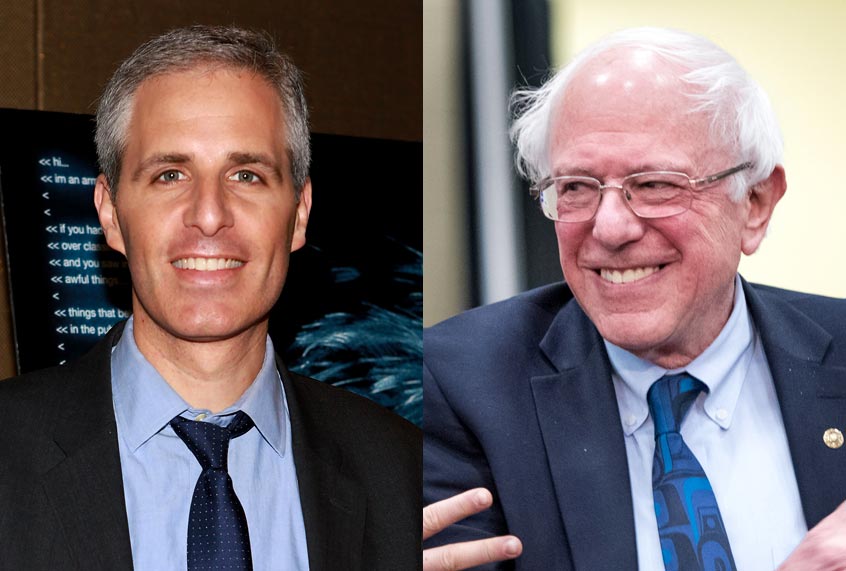

This is why it’s genuinely surprising and troubling to see that the Sanders campaign announced this week the hiring of journalist David Sirota, an inflammatory presence on Twitter (as well as a onetime Salon columnist), as a speechwriter and senior advisor.

The online backlash to this choice quickly devolved into a rules-lawyering debate over whether or not Sirota maintained appropriate ethical boundaries during his transition from his role as a journalist to his role as a campaign official. But the possibility that Sirota was double-dealing as a journalist and a Sanders surrogate is in some ways the least troubling aspect of this hire. What is more concerning are the larger issues this hire raises about the forthcoming primary campaign, and whether it will really be, as Sanders has professed, “about the issues we are fighting for, not about personalities or past grievances.”

The problem is that David Sirota lives for grievance-oriented fights. As Edward Isaac-Dovere of the Atlantic laid out in a piece examining his recent history, Sirota has an almost single-minded obsession with crapping on any Democratic politician perceived as competition for Bernie Sanders. In doing so, Sirota has sometimes argued in bad faith, such as when he framed individual donations from employees of oil and gas companies to Beto O’Rourke’s Senate campaign as “oil/gas industry campaign cash,” a move that Charles Pierce of Esquire characterized as “the laziest form of campaign gotcha.”

Sirota’s strategy as a pro-Sanders columnist was simple enough: He aggressively used any weapon he could find, focused on disqualifying the other candidates in the race as insufficiently progressive, churning out an endless stream of often half-baked accusations to scare votes away from them.

If Sirota plans to use this strategy to help Sanders win the 2020 primary campaign, it will be exceedingly unpleasant and, while it might win the primary, it will hurt Sanders in the general. It won’t make Sanders more popular, but it might drive down support for other Democratic candidates enough that Sanders can be dragged across the finish line in July 2020 with only the 27 percent support or thereabouts that he currently enjoys.

That’s exactly how Trump won the 2016 Republican nomination, after all. He systematically humiliated and disqualified his competitors until he was the last man standing, winning the bulk of delegates despite getting fewer than half of the overall GOP primary votes.

But after winning a bitter primary, Trump had a general election advantage that a Democrat in a similar position almost certainly wouldn’t have: Republicans fall in line.

Most of the voters who backed candidates like Ted Cruz or Marco Rubio or John Kasich overcame their anger and swiftly rallied to Trump’s side. GOP politicians like Sen. Lindsey Graham went from calling Trump a “kook” who was “unfit for office” to being among his fiercest defenders. Conservative politics rewards conformity and obedience to authority, and once Trump was the party’s anointed leader, he could count on conservatives supporting him until the end.

Trying to get Democrats to come together, on the other hand, is traditionally compared to herding cats, for good reason. The very things that make liberalism attractive, such as the emphasis on individuality and personal choice, also make liberals really bad at politics, which requires discipline and a willingness to put the interests of the group ahead of one’s personal wishes. The more negative the coming primary season is — the more it’s focused on personal or ideological attacks rather than positive arguments — the more likely it is that voters who support a losing candidate will become bitter and inclined to sit out the general election.

Sanders saw this himself in 2016, when a modest slice of his supporters, disproportionately enraged with Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party in general, helped throw the election to Trump. If Sanders really wants to be the nominee this time around, he might want to consider the danger of that happening in reverse: He could alienate people who didn’t vote for him in the primaries badly enough that they choose to sit out the general election.

Maybe the hiring of David Sirota isn’t a sign that things are about to get really ugly. Maybe Sirota will become an entirely different person in this new role. Maybe he won’t be empowered to indulge his instincts to go negative early and often. Maybe he plans to embrace a strategy of argue for Bernie Sanders instead of belittling and attacking the other guys. But it would be a lot easier to believe that if Sanders had hired someone more upbeat and forward-facing, rather than someone who makes enemies so easily and drives off potential supporters.

To be clear, I’m not trying to single out Sanders for criticism here, nor am I covertly arguing on behalf of some other candidate. All the Democrats in the 2020 field need to remember the dangers of fighting so hard for the primary that they forget the real task: Winning the presidential election and ending the reign of Donald Trump. Sanders is the first to make a major move that signals a willingness to go negative. I doubt he will be the last. Unfortunately, once someone breaks that seal, other candidates often feel they have to go negative in order to compete. Things could get really nasty, really fast.

Democrats must keep their eyes on the prize. Most of the factors that led to Trump’s flukish 2016 win are still in place: Voter suppression, Russian trolls, irresponsible social media, Fox News blanketing middle America with pro-Trump propaganda. The only thing Democrats can directly control, right now, is the level of rancor during the primary campaign. Trump could still win in 2020. Anyone who denies that in order to justify indulging in ugly internecine warfare is fooling himself. If that happens, we all pay the price.