Oil ministers gathered in Baku, Azerbaijan, the epicenter of an oil rush that took place a century ago. They came for the 13th meeting of the ministers of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) and non-OPEC.

Before the meeting, all eyes were on Saudi Arabia and Russia, the leading powers of the OPEC and non-OPEC countries respectively. Russia’s minister Alexander Novak and Saudi Arabia’s minister Khalid al-Falih had taken two different approaches to oil prices. Saudi Arabia, whose economy is in deep crisis, is eager to see oil prices rise to $95-$100 per barrel (the benchmark oil price is now at $67 per barrel). Russia, which has a more diversified economy, had planned on a price point at around $40 per barrel. The tension between them was to have stolen the spotlight for the meeting.

As it happened, all eyes went toward Venezuela and Iran, who now hope to be bailed out from their perilous situation by China and Russia.

Sanctions in the world of oil

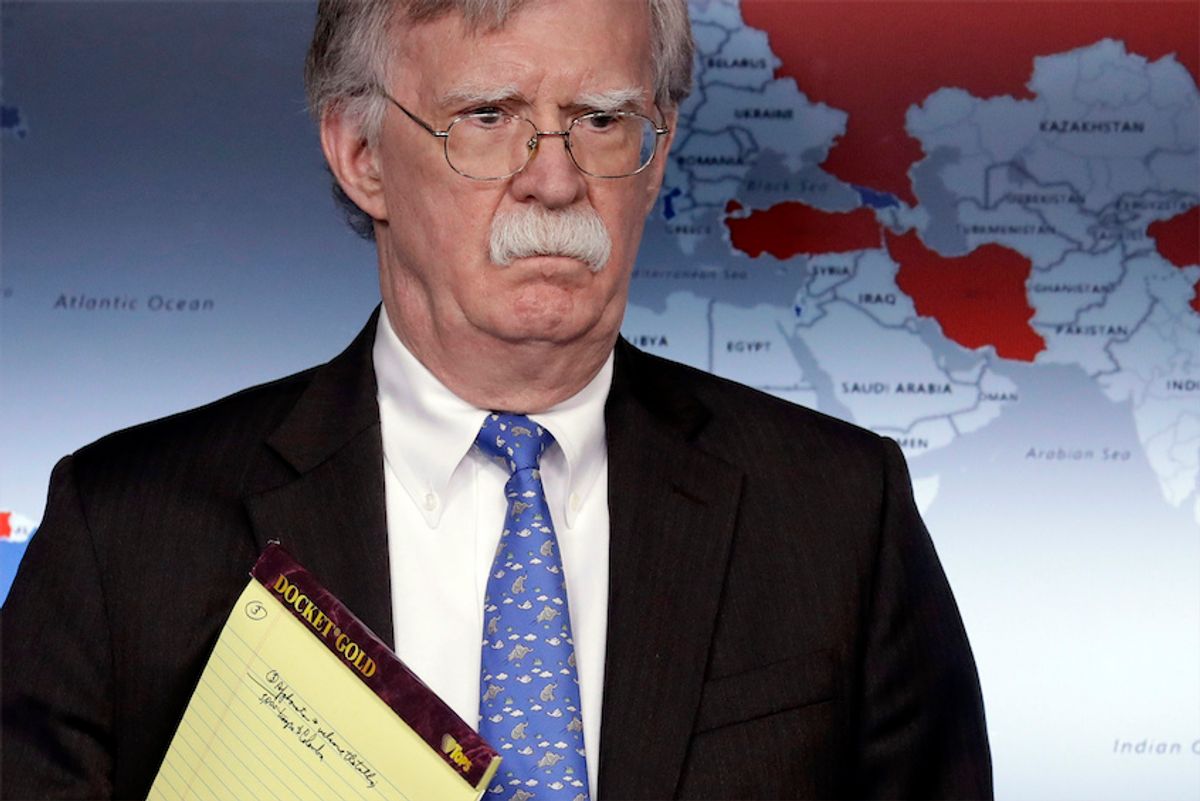

Both Venezuela and Iran are under very punitive U.S. sanctions. The U.S. government — led by National Security Adviser John Bolton — has been trying to urge all countries to cut oil production from both Iran and Venezuela. The pressure has had an impact. India, which was one of the main oil purchasers from both Iran and Venezuela, has cut its buying from Iran. At the Baku meeting, Venezuela’s oil minister Manuel Quevedo said that Venezuela would no longer be exporting oil to India. This is a major declaration. U.S. pressure on India, one of the world’s largest importers of oil, will turn the screws against both Iran and Venezuela.

Iran has been under U.S. sanctions for decades. A brief window of opportunity opened with the Iran nuclear deal. U.S. President Donald Trump has annulled that deal and has tightened U.S. sanctions on Iran. In November 2018, the United States gave waivers to eight countries (including India and China) to continue to buy Iranian oil for six months, namely until May. It wants Iran’s oil exports to be cut to under 1 million barrels per day (the current export total is 1.25 million barrels per day). Waivers will likely not be extended by the United States in May.

Venezuelan oil exports have been deeply impacted by the U.S. embargo. The United States was the largest purchaser of Venezuelan oil. That is no longer the case. U.S. sanctions against oil — and now against Venezuelan gold sales — have suffocated the finances of Venezuela. Venezuela is deeply vulnerable to these cuts given its reliance upon oil revenues to finance not only its government but its consumption.

India in the crosshairs

India’s right-wing government had long followed established Indian policy to buy oil from as many commercially viable sources as possible. Politics was not to enter the commercial deals made by India’s national oil company. This ended a decade and a half ago when India felt the pressure from the U.S. administration of George W. Bush to vote against Iran at the International Atomic Energy Agency in exchange for a promise of nuclear fuel for India’s nuclear reactors.

Nonetheless, over the years, India continued to buy Iranian and Venezuelan oil, regardless of the sanctions. Bolton has been putting considerable pressure on New Delhi to stop buying oil from Iran and from Venezuela.

Since last February, India has cut its oil imports from Iran by 60 percent. It now buys only 260,000 barrels per day (the U.S. waiver allows India to buy 300,000 barrels per day). Iran’s oil minister Bijan Zangeneh said last year that Iran would offer India free shipping and extended credit to increase Indian oil purchases. But this was to no avail. The cuts continued and will continue further before the May deadline.

In February, the Indian oil minister Dharmendra Pradhan met with Venezuela’s oil minister Manuel Quevedo in New Delhi to discuss increased oil purchases, including Indian investment in Venezuela’s oil fields. Just a few days ago, there was a serious conversation in New Delhi about India paying Venezuela in rupees for the oil. Bolton was furious. He called India’s National Security Adviser Ajit Doval to threaten him that if India continued to buy Venezuelan oil, this would “not be forgotten.” On March 12, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo told India’s Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale that India should not become an “economic lifeline” for Venezuela.

In February, one of the world’s largest commodity traders, Trafigura, said it would halt trading oil with Venezuela. India dealt with Trafigura and with Litasco SA to handle the oil deals. The pressure on India increased when freight charges increased, and insurance posed a serious problem.

India goes into its parliamentary election season, with the result to come in late May. There is uncertainty as to the result of the election, an uncertainty that shapes India’s further oil imports.

Turn to Eurasia

Hesitancy by India is perhaps the reason why Venezuela’s oil minister told the Baku conference that his country would not be exporting oil to India any longer. This is very significant news.

Quevedo said that Venezuela would now largely export oil to China and Russia. Both China and Russia, powers unwilling to fully buckle to U.S. pressure, have been consistent buyers of both Venezuelan and Iranian oil. They have also both invested heavily in these economies, buying debt and investing in infrastructural projects.

It is important that Venezuela’s president Nicolas Maduro moved the headquarters of Venezuela’s European oil subsidiary from Lisbon to Moscow. Quevedo will go to Moscow in April for the inauguration of the office. At Baku, Quevedo said he would meet with Russia’s energy minister Novak and the Rosneft head Igor Sechin.

It might be worth recalling that the United States has sanctions in place against Russia and is in the midst of a trade war against China. If the new bill in the U.S. Senate — Defending American Security from Kremlin Aggression Act (2019) — gets any traction, it will only increase tensions between Russia and the United States. There is little appetite in Moscow or Beijing to conform to U.S. policy, particularly if there are commercial advantages for Russia and China.

On March 11, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Evrofinance Mosnarbank—a Russian-Venezuelan commercial bank — for assisting the Venezuelan oil firm to go around U.S. financial sanctions. There’s no sign that this sort of activity will end. In fact, if Russia increases its oil buys from Venezuela, it is likely to develop new financial arrangements to allow the two countries — and China — to trade with each other.

One indicator that Russia will not give up on Venezuela is that Rosneft has sent shipments of heavy naphtha to Venezuela despite the U.S. embargo. This naphtha is necessary to extract heavy crude oil. Two Rosneft tankers — Serengeti and Abilani — will take 1 million barrels of naphtha from Europe to Venezuela, which had almost run out of this diluent. Rosneft has loaned Venezuela $6.5 billion since 2014, with the Venezuelan oil firm in debt to Rosneft to the tune of $2.3 billion. This investment is significant and only deepens the Russian stake in Venezuela.

Neither China nor Russia is willing to see the United States overthrow the government in Venezuela. Both have commercial interests in the country. Both also seek to deepen a more diversified global order, with the United States no longer seen as a viable policeman. The test for their commitment to multi-polarity will be in how China and Russia hold the line on the United States’ attempt to squeeze Iran and Venezuela. If China and Russia are able to withstand the U.S. pressure — and build alternative financial mechanisms — then a multi-polar order can come into being; if they fail, then the world remains under uni-polar dominance.

Shares