Philanthropy has long been a way for wealthy families whose fortunes have been built on the suffering and exploitation of others to rebrand themselves. Hefty donations to museums or other public institutions can obscure or even outright cleanse the money's origins while perpetuating a family's legacy via a new wing or center named in the donor's honor. The institutions that benefit, the donors themselves, and even the people the funded organizations serve can feel good about these exchanges: no matter how the money was amassed, the act of handing profits over to a nonprofit transforms it automatically into goodwill, helping to preserve or make accessible art or cultural programs.

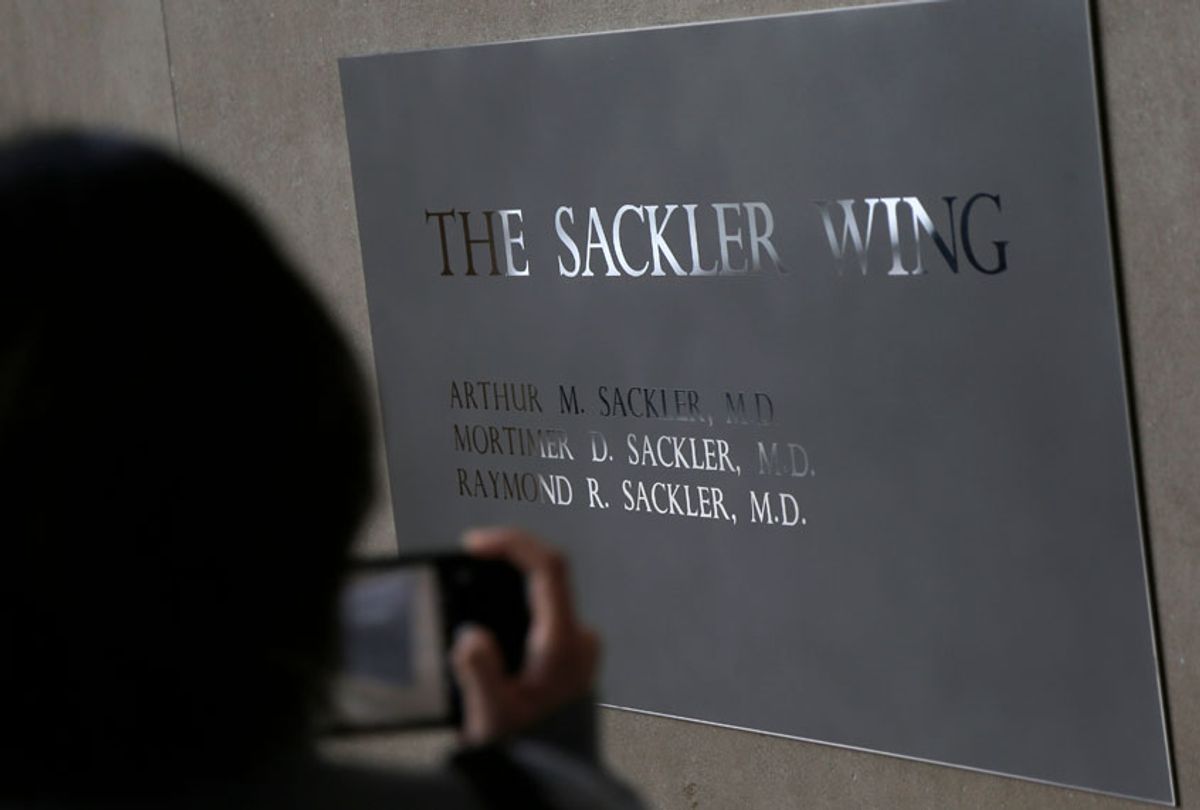

But the beginnings of a critical reckoning seem to be taking place, with some of the world's most prestigious museums and institutions questioning the ethics of turning a blind eye to dirty money, and in some cases, cutting ties with notoriously ruthless donors. At the center of this shift is the Sackler family, who for decades amply supported museums around the world, as well as universities and medical institutions. There's the Sackler Institute at Columbia University; at Oxford, the Sackler Library; Louvre visitors will find the Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities. There are many, many more examples of Sackler gifts turning into Sackler wings, courtyards, galleries, stairs, centers, educational labs and even escalators (at the Tate Modern in London) .

The Sackler family has amassed a multi-billion dollar fortune thanks in large part to OxyContin, the prescription painkiller that has been central to the opioid crisis. The Sacklers own Purdue Pharma, which introduced the drug in 1996. While many other prescription painkillers have contributed to the ongoing and deadly crisis, "Purdue Pharma was the first to achieve a dominant share of the market for long-acting opioids, accounting for more than half of prescriptions by 2001," according to Esquire.

Two bombshell articles — one from Esquire, titled "The Secretive Family Making Billions From the Opioid Crisis" and the other from the New Yorker, titled, "The Family that Built an Empire on Pain" — have spotlighted in recent years the Sackler family's acquisition of wealth and unique role in the opioid epidemic. As Patrick Radden Keefe wrote in the New Yorker, "The Sackler dynasty’s ruthless marketing of painkillers has generated billions of dollars—and millions of addicts."

In the past week, two museums subsequently have decided to distance themselves from the Sackler empire. The Tate museums in London and the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York announced that they would no longer accept Sackler donations. "Britain’s National Portrait Gallery announced it had jointly decided with the Sackler Trust to cancel a planned $1.3 million donation, and an article in The Art Newspaper disclosed that a museum in South London had returned a family donation last year," the New York Times reported.

Now, other Sackler beneficiaries are also following suit. The Metropolitan Museum and the New York Academy of Science are reportedly reviewing their donation policies in light of the legal and public scrutiny around Purdue Pharma.

While the Sacklers' immediate connection to OxyContin is far from new, the rise of the opioid crisis has raised many questions about who to blame and how it got so dire. Purdue Pharma and eight Sackler family individuals are currently being investigated and sued for potentially criminal and corrupt involvement. "Documents submitted in court this year in a lawsuit suggested that, far from being bystanders to the epidemic, family members directed company efforts to mislead the public and doctors about the dangers of abusing OxyContin," the Times reported. (The Sacklers deny the accusations and claim they are committed to addressing "this complex public health crisis.")

A Sackler trust and family foundation in Britain responded to the rebuke from museums, saying they would pause their philanthropy for the time being. "The current press attention that these legal cases in the United States is generating has created immense pressure on the scientific, medical, educational and arts institutions here in the U.K., large and small, that I am so proud to support," said Theresa Sackler, chair of the Sackler Trust, in a statement, obtained by the Times. "This attention is distracting them from the important work that they do."

In the art world, where cultural institutions often rely heavily on the generosity of donors, snubbing the Sackler family is no small thing. And yet, the rebuke of the Sackler money is only the beginning, as museums, artists and patrons confront the broader questions of institutional money trails.

In the U.K., there has been pushback against the sponsorship of exhibitions from an oil company, and in New York, one artist withdrew from an exhibition at the Whitney in protest because the museum's vice chairman is Warren Kanders, who runs a company that assembles body armor and tear gas for law enforcement and the military. Tear gas from Kanders' company was sprayed against Central American asylum seekers, many of whom were women and young children, at the U.S. - Mexico border last fall. Nearly 100 Whitney staff members also signed a letter charging the museum to develop and distribute a "clear policy around trustee participation," and that the institution "consider asking" for Kanders' resignation.

However, the Guggenheim's decision to sever ties with the Sackler family is perhaps the most stunning, as the museum has received millions from the Sackler dynasty, and one member of the Sackler family sat on the museum's board for almost two decades. The Guggenheim also became the first American institution to overtly distance itself from the Sackler family, according to the Times.

The Guggenheim was the site of a powerful protest last month, in which photographer Nan Goldin, who overcame an OxyContin addiction, joined other activists to drape banners and drop thousands of slips of white paper from the famed spiraling balconies in protest of donations from the Sackler family. The small white papers were "a reference to a court document that quoted Richard Sackler, who ran Purdue Pharma, heralding a 'blizzard of prescriptions that will bury the competition,'" the Times reported.

While this is only the beginning, and there are many institutions, most especially in the U.S., that have shown resistance to returning donations by the Sackler family or other ethically questionable sources, the momentum from the Guggenheim may propel other prestigious U.S. nonprofits to act.

"This is blood money and should be returned," David Callahan, author and the founder of the website Inside Philanthropy, told the Guardian. "It’s not easy to give back money or get rid of a name, but not taking any new money, that would seem to be an easier call for institutions and pretty obviously a smart decision at this point."

The philanthropy industry is deeply complicated, and it's long been used to burnish or even refurbish the reputations of the wealthy, at times undeservedly so. There's a credible argument to be made that any family that has been able to rack up billions and donate millions has been able to do so because of the exploitation of others. So figuring out where to draw the line regarding big donors, especially when it comes to often woefully underfunded cultural institutions, can be unclear. But for decades, many organizations have not even bothered to try.

"Historically, museum audiences have not shown evidence of being terribly concerned about sources of income for museums," Susie Wilkening, a museum consultant in Seattle, told the Times. Her words recall the issue of stolen Nazi art, as well the pervasiveness of cultural philanthropy from Andrew Carnegie and the Rockefellers, and more recently the Koch brothers — wealthy families whose empires thrived in part by being anti-union or destructive to the environment, among other harmful practices.

Therefore, attempting to devise some sort of ethical and transparent system should be a welcomed endeavor among cultural institutions. After all, what are museums teaching about human achievement and culture and artistry if they routinely look the other way when it comes to dirty money? Ultimately, a family that profits off of addiction, or funds opposition to climate change, should not be able to cleanse their legacies through our most beloved cultural institutions. The Sackler family, for their part, could consider paying damages to the victims of the opioid crisis instead.

Shares