When Karolyn Schrage first heard about the “dominoes gang” in the health clinic she runs in Joplin, Mo., she assumed it had to do with pizza.

Turns out it was a group of men in their 60s and 70s who held a standing game night — which included sex with one another. They showed up at her clinic infected with syphilis.

That has become Schrage’s new normal. Pregnant women, young men and teens are all part of the rapidly growing number of syphilis patients coming to the Choices Medical Services clinic in the rural southwestern corner of the state. She can barely keep the antibiotic treatment for syphilis, penicillin G benzathine, stocked on her shelves.

Public health officials say rural counties across the Midwest and West are becoming the new battleground. While syphilis is still concentrated in cities such as San Francisco, Atlanta and Las Vegas, its continued spread into places like Missouri, Iowa, Kansas and Oklahoma creates a new set of challenges. Compared with urban hubs, rural populations tend to have less access to public health resources, less experience with syphilis and less willingness to address it because of socially conservative views toward homosexuality and nonmarital sex.

In Missouri, the total number of syphilis patients has more than quadrupled since 2012 — jumping from 425 to 1,896 cases last year — according to a Kaiser Health News analysis of new state health data. Almost half of those are outside the major population centers and typical STD hot spots of Kansas City, St. Louis and its adjacent county. Syphilis cases surged at least eightfold during that period in the rest of the state.

At Choices Medical Services, Schrage has watched the caseload grow from five cases to 32 in the first quarter of 2019 alone compared with the same period last year. “I’ve not seen anything like it in my history of doing sexual health care,” she said.

Back in 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had a plan to eradicate the sexually transmitted disease that totaled over 35,000 casesnationwide that year. While syphilis can cause permanent neurological damage, blindness or even death, it is both treatable and curable. By focusing on the epicenters clustered primarily throughout the South, California and in major urban areas, the plan seemed within reach.

Instead, U.S. cases topped 101,500 in 2017 and are continuing to rise along with other sexually transmitted diseases. Syphilis is back in part because of increasing drug use, but health officials are losing the fight because of a combination of cuts in national and state health funding and crumbling public health infrastructure.

“It really is astounding to me that in the modern Western world we are dealing with the epidemic that was almost eradicated,” said Schrage.

Grappling With The Jump

Craig Highfill, who directs Missouri’s field prevention efforts for the Bureau of HIV, STD and Hepatitis, has horror stories about how syphilis can be misunderstood.

“Oh, no, honey, only hookers get syphilis,” he said one rural doctor told a patient who asked if she had the STD after spotting a lesion.

In small towns, younger patients fear that their local doctor — who may also be their Sunday school teacher or basketball coach — may call their parents. Others don’t want to risk the receptionist at their doctor’s office gossiping about their diagnosis.

Some men haven’t told family members they’re having sex with other men. And still more have no idea their partner may have cheated on them — and their doctors don’t want to ask, according to Highfill.

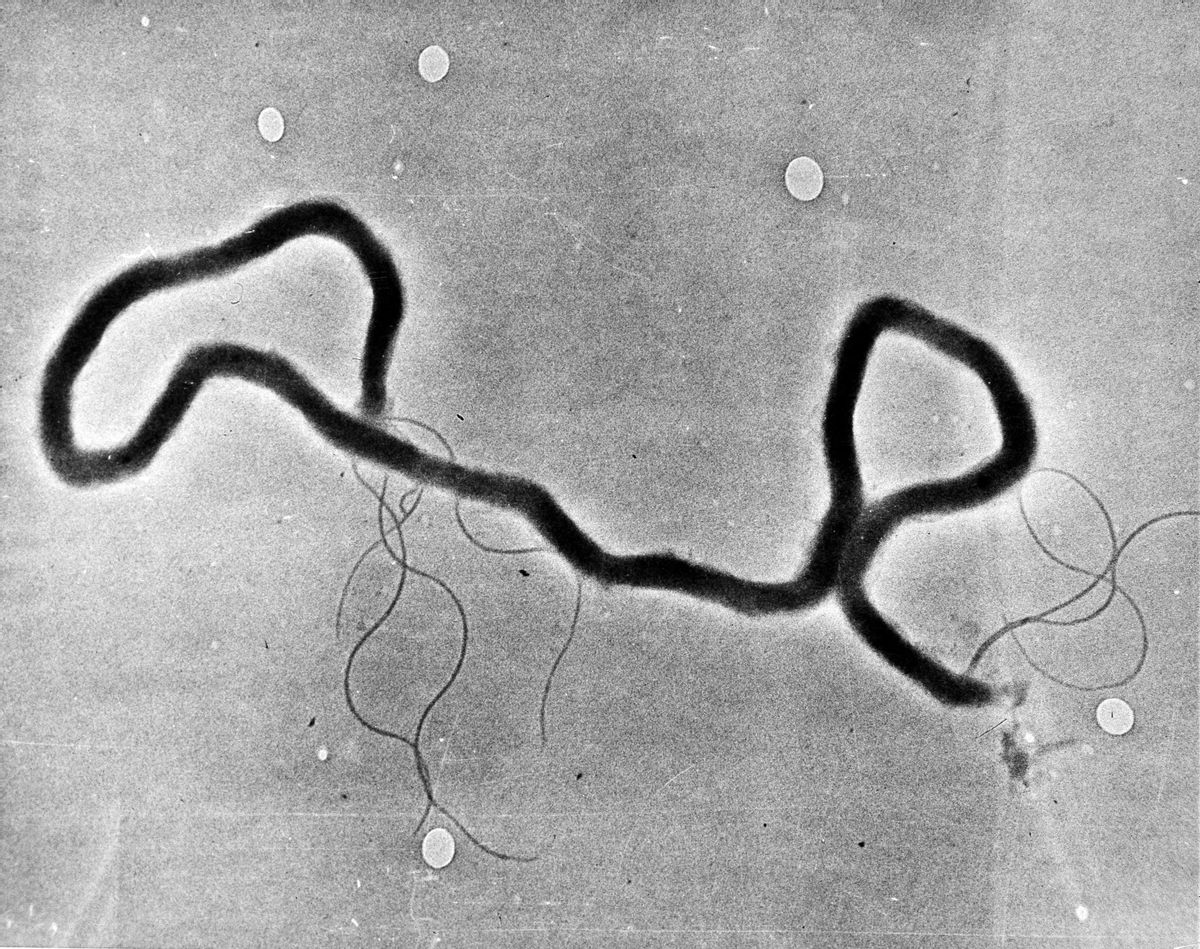

It’s even hard to expect providers who haven’t seen a case of syphilis in their lifetime to automatically recognize the hallmarks of what is often called the “great imitator,” Highfill said. Syphilis can manifest differently among patients, but frequently shows up for a few weeks as lesions or rashes — often dismissed by doctors who aren’t expecting to see the disease.

Since 2000, the current syphilis epidemic was most prevalent among men having sex with men. Starting in 2013, public health officials began seeing an alarming jump in the number of women contracting syphilis, which is particularly disturbing considering the deadly effects of congenital syphilis — when the disease is passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus. That can cause miscarriage, stillbirth or birth deformities.

Among those rising numbers of women contracting syphilis and the men who were their partners, self-reported use of methamphetamines, heroin or other intravenous drugs continues to grow, according to the CDC. Public health officials suggest that increased drug use — which can result in a pattern of risky sex or trading sex for drugs — worsens the outbreaks.

That perilous trend is playing out particularly in rural Missouri, argues Dr. Hilary Reno, an assistant professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis who is researching syphilis transmission and drug use in the state. Tracking cases from 2015 through June 2018, she found that more than half of patients outside of the major metropolitan areas of Kansas City and St. Louis reported using drugs.

Less Money, More Problems

Federal funding for STD prevention has stayed relatively flat since 2003, with $157.3 million allocated for fiscal year 2018. But that amounts to a nearly 40% decrease in purchasing power over that time, according to the National Coalition of STD Directors.

In Missouri, CDC annual funding has been cut by over $354,000 from 2012 to 2018 — a 17% decrease even as the number of cases quadrupled, Highfill said.

Iowa, too, has seen its STD funding cut by $82,000 over the past decade, according to Iowa Department of Health’s STD program manager George Walton.

“It is very difficult to get ahead of an epidemic when case counts are steadily — sometimes rapidly — increasing and your resources are at best stagnant,” Walton said. “It just becomes overwhelming.”

Highfill bemoaned that legislatures in Texas, Oregon and New York have all allocated state money to raise awareness or provide transportation to local clinics. Missouri has not allocated anything.

A New Playing Field

In the digital age, fighting syphilis is much harder for public health responders, said Rebekah Horowitz, a senior program analyst on HIV, STDs and viral hepatitis at the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

The increased use of anonymous apps gives people greater access to more sexual partners, she said. Tracking down those partners is now much harder than camping out at the local bar in town.

“We can’t get inside of Grindr and do our traditional public health efforts,” she said.

That’s not to say Highfill’s department hasn’t tried. It has engineered a series of educational ads on Instagram, Grindr and Facebook displaying messages such as “Knowledge looks good on you.”

Highfill would love to do more — if Missouri had the money.

Public health clinics nationwide have also had to limit hours, reduce screening and increase fees that can reach $400. And some run by health departments across the country have been forced to close — at least 21 in 2012 alone, according to CDC data.

In Missouri, restrictions on Planned Parenthood’s Medicaid reimbursements that were passed last year in the legislature, and are again under debate, mean the nonprofit organization cannot be reimbursed for STD treatment for some patients.

That is another crack in the already failing public health infrastructure, said Reno, the Washington University professor who also serves as the medical director of the St. Louis County Sexual Health Clinic.

“We have a system that’s not even treading water,” she said. “We are the ship that is listing to the side.”

Shares