One by one, Democratic presidential hopefuls stormed Wisconsin. They brought bravado, promising to win back the midwest after the party’s Blue Wall collapsed in 2016. Beto O’Rourke delivered flattery, telling voters that they’d not only play host to the party’s 2020 convention, but that “this state is fundamental to any prospect we have of electing a Democrat to the presidency in 2020 and being ready to start on Day One in 2021.”

Some even dropped shade. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, of neighboring Minnesota, obliquely referenced Hillary Clinton’s neglect in 2016 and suggested Democrats narrowly lost the state because they didn’t bother showing up. “We’re starting in Wisconsin,” she said, “because, as you remember, there wasn’t a lot of campaigning in Wisconsin in 2016.”

Twenty would-be presidents got an early start on 2020, many of them campaigning on hard-to-deliver democracy reforms such as an end to gerrymandering and the Electoral College, let alone adding justices to the U.S. Supreme Court, or Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico as states.

And in their haste to promote their own candidacies and longshot ideas to win back the White House, they overlooked a winnable race happening in Wisconsin in 2019.

So while Beto jumped atop the counters of hipster Madison coffee shops and Democrats argued whether a millennial mayor, a centrist former vice president nearing 80, or a female U.S. senator would make a stronger candidate against Donald Trump 19 months from now . . . Democrats lost an election that could doom the party’s chances in Wisconsin for the next decade.

When Brian Hagedorn defeated Lisa Neubauer earlier this month and captured a state Supreme Court judgeship by just over 6,000 votes, it cemented conservative control over Wisconsin’s highest court — and could reinforce the GOP’s gerrymandered advantages in the state legislature for many more years to come.

Why have leading Democrats learned nothing from this last decade? Ten years ago, a historic blue wave elected our first black president, sent a Democratic supermajority to the U.S. Senate, and returned a Democratic House. Overconfident Democrats, certain that changing American demographics would give them an advantage for a generation, then fell asleep on the all-important 2010 state legislative elections, down-ballot races crucial to determining which party would dominate redistricting — and create the truly decisive advantage.

Republicans turned those local races into consequential national battlegrounds. The Republican State Leadership Committee invested $30 million in flipping state legislative chambers with a plan called REDMAP, short for the Redistricting Majority Project. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, GOP strategist Karl Rove name-checked neighborhoods as tiny as Brushy Creek in Round Rock, Texas, and Murrysville Township in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, as being essential to a big-picture plan. “Republican strategists,” Rove revealed, “are focused on 107 seats in 16 states. Winning these seats would give them control of drawing district lines for nearly 190 congressional seats.”

It worked brilliantly. “The DNC, they just whistled past the graveyard,” Steve Israel, the former New York congressman who took over the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee after the party’s 2010 debacle, told me. Democrats vowed never to fall asleep on redistricting again. Barack Obama named fixing gerrymandering the top political priority of his post-presidency. Activists promised that they understood the importance of off-year elections and down-ballot races.

Then the 2018 wave swept Nancy Pelosi in as House Speaker, a cavalcade of Democrats announced for the White House, small donors scattered gifts to ensure their favorites earned a spot on the presidential debate stage — and once again, an overconfident party snored through a race it could not afford to lose.

Just how important was this Supreme Court race? Well, one of the most brutal and long-lasting GOP gerrymanders took place in Wisconsin. In 2018, Democrats swept every statewide office, and defeated the two-term Republican governor, Scott Walker. Tammy Baldwin won re-election to the U.S. Senate by 11 percentage points. Democratic assembly candidates captured more than 200,000 votes statewide than Republicans.

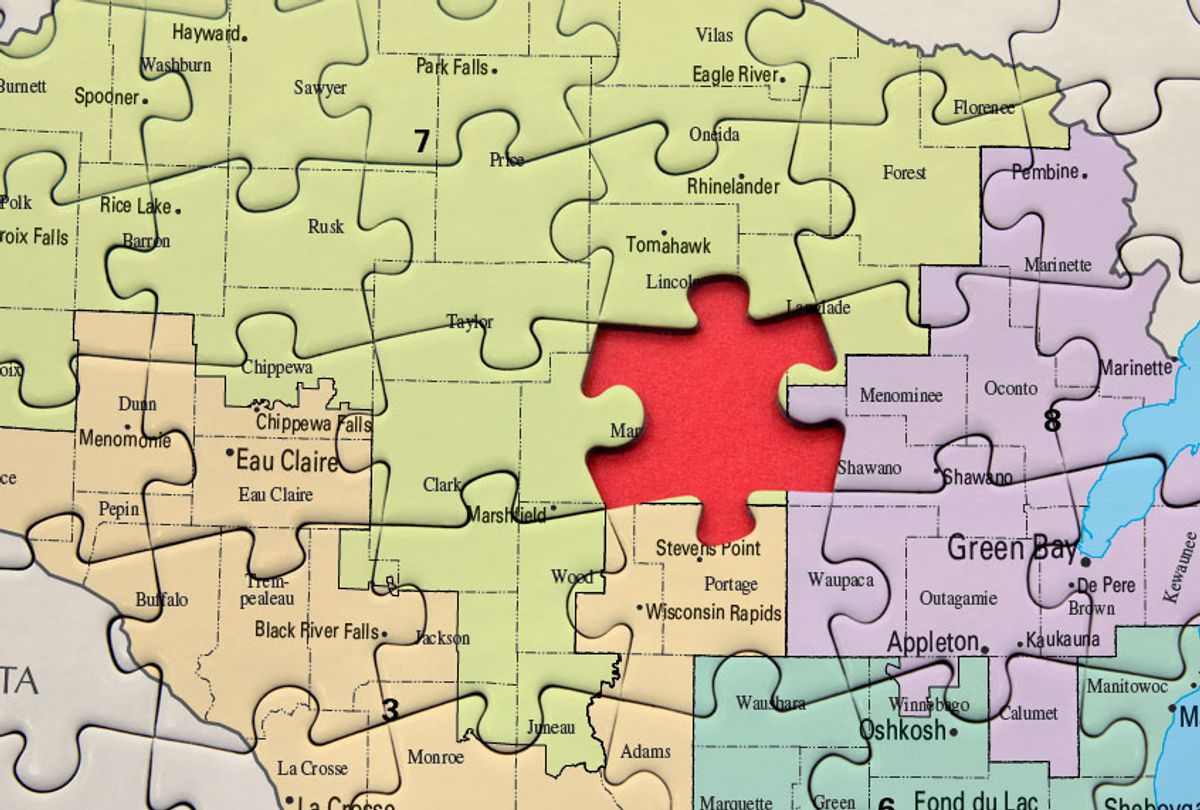

The Republican gerrymander, however, provided a red seawall against what was a ferocious blue wave. With dramatically fewer votes, Republicans nevertheless won a 63-36 majority. Democrats won 53 percent of the vote, but merely 36 percent of the seats. Wisconsin’s maps, surgically crafted by Republicans in 2011 to engineer just this result, even in a wave year, simply no longer respond to shifts in the electorate. (In 2012, a majority of Democratic votes also produced a supermajority of Republicans. By 2016, Wisconsin politicos surrendered hope of flipping any seats, and 49 percent of local legislative races lacked a major-party challenger.)

If voters couldn’t dismiss an entrenched legislature at the ballot box, they’d need help from the courts to restore democracy and self-rule. In 2017, a federal court declared this an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, resoundingly dismissed the argument that the state’s political geography created a natural GOP advantage, and ordered the map redrawn. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, stayed that order and then sent the case back to the lower courts on a technical issue.

The Hagedorn/Neubauer race mattered so much because, with this entire decade likely lost to a unconstitutional map, Wisconsinites had to begin looking ahead to the next district lines, which will be drawn by the Republican legislature after the 2020 census, subject to a likely veto by the new Democratic governor. That would push the hot potato straight to the state Supreme Court as the deciding voice. Democrats needed to win two statewide elections — this year and next — to flip a 5-4 Republican edge the other direction. Win this year, and next year’s contest would be easier, since the 2020 election would be held the same day as Wisconsin’s Democratic presidential primary. They couldn’t pull it off.

You need not be a partisan to find this situation dangerous. Wisconsin’s state assembly maps have locked in a nearly unbeatable Republican edge, even when hundreds of thousands more voters prefer Democrats. When maps are unresponsive to the public will and shifts in voter opinion, it calls into question the very notion of representative democracy. No political party should have that power. When district lines are warped by politicians, it distorts democracy, helps push government to the extreme, and makes all sides less accountable. REDMAP tilted democracy for all of us: Gerrymandering created the seat that Freedom Caucus chairman Mark Meadows now holds. It created the North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania congressional maps that sent a combined 35 Republicans and 12 Democrats to Washington for most of this decade, artificially inflating the GOP edge. And now those states, and other battlegrounds, produce legislation on voting and reproductive rights that are far from the mainstream, but voters have little ability to hold those lawmakers accountable.

But while both parties have taken advantage of this process over our history, the GOP’s REDMAP strategy allowed them to draw nearly all of today’s most gerrymandered maps. The courts appear reluctant to get involved. That means Democrats must win elections for us to find a way out of this frightening morass. Specifically, it means that Democrats must win statewide judicial races and local legislative contests. Like it or not, absent court action, the nature of our two party system means that a solution to toxic maps requires Democrats to win back seats at the table before 2021 redistricting, if only to ensure maps aren’t wildly rigged in one direction. If two dozen Democrats want to seek the White House, fine. They should also understand that they will accomplish nothing so long as the maps are tilted the other way -- and then they should join a nonpartisan fight for fairness. A thoughtful democracy platform is so terrific. But so is helping local candidates win local elections.

At least two Democrats understand this. Eric Holder, the former attorney general, decided not to run for president and has focused instead on running the National Democratic Redistricting Commission. Holder spent endless days campaigning in Wisconsin and helped raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for the race. Terry McAuliffe, as well, the former Virginia governor, decided not to seek the White House and has pushed hard to get the 2020 candidates to visit his state this year, not next, because legislative elections this fall will determine who draws Virginia’s maps in 2021. Likewise, many grassroots groups, including Future Now, Run For Something and Flippable, fully grasp the stakes.

In recent days, South Bend, Ind., mayor Pete Buttigeig and even O’Rourke have sounded committed to campaigning up and down the ballot. However, when O’Rourke stood atop that coffee shop counter last month, he sounded like he got it as well. "The only way to win is to show up. I have found that in every political race I’ve run, from city council to Congress to U.S. Senate. When we don’t show up, we get what we deserve, and that is to lose. So i’m going to show up everywhere for everyone," he said.

Trouble is, he meant that he’d show up everywhere to talk to everyone about . . . himself. That attitude changes, or our entire democracy pays the price.

Shares