On April 15, people around the world watched in horror as a voracious fire consumed the medieval wooden roof of Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral and felled its spire.

The following day brought some measure of relief: Despite the building’s wrenching losses, its masonry structure was largely intact, and many of its precious relics had been swiftly and lovingly removed by a human chain of church officials and firefighters. The building had steadfastly endured the destructive flames.

Since then, Notre Dame has been hailed as a stable and enduring symbol of French identity.

But it would be more accurate to say that the cathedral’s importance comes from the very instability of its meaning.

Originally completed in 1345, by the early 19th century Notre Dame stood in a state of dire disrepair. It took an idiosyncratic young architect, moved by Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” to fashion a new meaning for the building — one that, ironically, looked nostalgically to the past for inspiration.

"The book will destroy the edifice"

In 1831, when Victor Hugo published his famous novel “Notre Dame de Paris” — known in English as “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” — the country was experiencing rapid social, political and industrial change.

The cathedral, meanwhile, had fallen by the wayside. Years of neglect, blinkered renovation efforts and the anti-Catholic zeal of the French Revolution had left the once-regal building in ruins.

Set in the 15th century, the novel alluringly evoked a different period in French history. In the novel, Hugo lamented that the printing press had supplanted architecture as the primary communicator of civilization’s cherished values. In one of the book’s most famous moments, the archdeacon Frollo points sadly to a printed book on his table.

“Alas! This will kill that,” he laments, directing his finger to the cathedral looming magisterially outside his window. He continues, “The book will destroy the edifice.”

Like other Romanticist writers and artists, Hugo imagined the Middle Ages as a simpler time, an era when society was governed by pure faith. He believed that back then, the cathedral was able to inspire the masses and guide them toward a life of devotion and morality. Hugo hoped that his novel might spur the building’s rebirth, allowing it to renew France’s ethical core during the Industrial Revolution.

One architect, attracted to the picturesque history on view in Hugo’s novel, would ultimately heed his call.

An architect reaches longingly for the past

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc was a teenager when Hugo’s novel was published. The book affirmed Viollet-le-Duc’s suspicion that his own age’s riot of styles and tastes reflected the unwieldy chaos of modern life.

Like Hugo, he sought to capture France’s “authentic” past and, like Hugo, was drawn to the Middle Ages.

For this reason, he refused to enroll in the École des Beaux-Arts, the main training ground for France’s architects, because of the school’s dogmatic focus on classical architecture. He opted instead to learn on the job, working for architects around Paris while studying the city’s medieval architecture in his spare time.

In 1842, the government announced a competition for Notre Dame’s restoration and the 28-year-old Viollet-le-Duc threw his hat into the ring. By then, he had already established his reputation as an expert in the restoration of medieval buildings.

But for him, restoration was about more than touching up an existing form. It meant breathing life into a building by transforming it.

As he later wrote, “To restore a building is not to preserve it, to repair or rebuild it; it is to reinstate it in a condition of completeness which could never have existed at any given time.” Viollet-le-Duc knew that the very act of restoring old buildings was, itself, a modern notion.

A symbol of stability in uncertain times?

Thus, Viollet-le-Duc’s winning entry would not simply aim to preserve the cathedral as it then stood. Instead, he sought to revive the building’s mythical past.

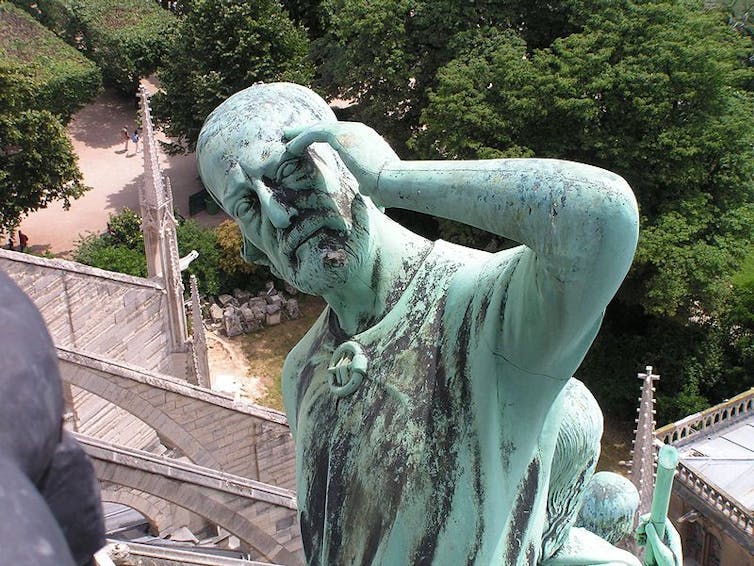

During the restoration, Viollet-le-Duc redesigned and rebuilt the medieval spire, which had been removed in the 1780s due to its vulnerability in high winds (an absence that had appalled Hugo). He also sprinkled the building with its now-famous gargoyles in accord with Hugo’s atmospheric depiction of a building adorned with “grinning monsters.”

Viollet-le-Duc’s renovated cathedral — the version that we know today — is a product both of the French Middle Ages and of its architectural revival in the 19th century. Like Hugo, Viollet-le-Duc romantically conceived medieval architecture as a stable bulwark against his own uncertain times. He wanted to intensify what he saw as the building’s mystical power — its ability to speak to France’s past at a time when the forces of modernity were threatening to sweep its traces away.

Viollet-le-Duc also ensured his own role in the rehabilitation would forever be preserved: His likeness appears in the face of a copper statue of St. Thomas at the base of the spire.

By good fortune, this statue was removed for the renovation just last week and was spared from the conflagration.

Harmonia Amanda/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Since the fire, many writers have correctly pointed out that the catastrophe is also only one episode in a much longer story of architectural survival.

Notre Dame will certainly live on in some new form; France has been offered astronomical donations for the purpose. In fact, a competition to redesign the spire has already been announced.

Much like Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration, this newest version of Notre Dame will look to the past — selectively — to ensure the building’s future.![]()

Julia Walker, Assistant Professor of Art History, Binghamton University, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares