Last week, the U.S. used the threat of its veto power and generalized clout to weaken a United Nations Security Council resolution against rape in war zones. The watered-down version, which passed on April 23, excludes all references to sexual and reproductive health.

The issue, apparently, was that the resolution mentioned family planning clinics. For anti-abortion extremists in the Donald Trump administration, such as Vice-President Mike Pence, the worry was that a woman from a war zone might choose to terminate a pregnancy rather than have her rapist’s child.

We should expect as much from America’s religious right. Since emerging as a major force in the Republican Party in the 1980s, conservative evangelicals have opposed everything that the civil rights and women’s rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s achieved. At home and abroad, they oppose LGBTQ rights, sex education and birth control along with abortion.

Their leaders claim to be men of faith, but they seem 100 per cent certain that God is on their side, which is why they wouldn’t flinch at telling a traumatized woman to have that baby.

The puzzle is why these views have wider purchase in Trump’s America, even from those — like Trump himself — who aren’t pious. Why do men like Trump and Pence understand each other so well? Contemporary politics aside, the answer has to do with a particular kind of religious nationalism with deep roots in American history.

International law and American vengeance

By and large, the revolutionary leaders of the 1770s and 1780s weren’t religious nationalists, if only because they wanted recognition as a neutral country that honoured treaties and respected international law. But the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars quickly taught Americans that stronger nations like Great Britain made their own rules.

The Founders’ respect for the international community thus fed a sense of betrayal and victimization. “Never before has there been an instance of a nation’s bearing so much as we have borne,” wrote Thomas Jefferson on the eve of the War of 1812.

For many, the United States now seemed like the only lawful nation — a suffering Christ, surrounded by cruel foes and corrupt onlookers. From there it was an easy step to see America as an angry God, slow to wrath but terrible in vengeance.

In 1819, one congressman called Andrew Jackson, the hero of the war, the one man “appointed by Heaven to tread the wine press of Almighty wrath.” Another argued that America had always shown “extraordinary forbearance” until, at length, “the nation rose in the majesty of its strength, and hurled destruction upon the foe!” The dream of American omnipotence was born.

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, that dream had to compete with older traditions that were more respectful of international law. Most Americans still balked at the idea of their country as an empire, even if it acted that way with Indigenous peoples and weaker countries. Along with the simple fact that the U.S. had to share the world’s stage with the European powers, these factors held religious nationalism in check.

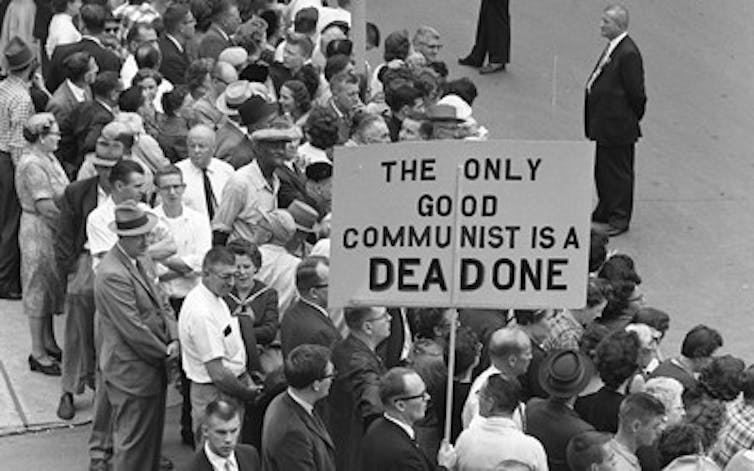

Good versus evil

Much as the long struggle against Great Britain had shaped the first generation of Americans, however, the great battle against the Soviet Union bred a special sense of divine mandate in the post-Second World War decades. Once again, a wide range of Americans saw their country as God’s lieutenant, with the right and duty to judge and punish other countries.

Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs, CC BY

The United States was leading an epic battle “between right and wrong and good and evil,” Ronald Reagan told the National Association of Evangelicals in 1983. Its power came directly from the Almighty, and “must terrify and ultimately triumph” over its foes..

Reagan wasn’t especially religious, but that didn’t matter — his conviction that America alone could destroy evil resonated with the emerging evangelical right, with its absolute views of the saved versus the damned. By contrast, international law seemed not only weak but also corrupt, a degrading spectacle of diplomacy, compromise and co-existence.

Much the same can be said of Trump, a vulgar libertine with overwhelming support from evangelicals. Their alliance isn’t just a marriage of convenience, but a shared belief in America’s dominion over a fallen world, an insatiable need to inflict their notions of right and wrong on all Creation.

In the case at hand, evangelicals push for a total ban on any U.S. support for abortion providers, anywhere in the world, and the administration obliges because it disdains international rule-making of any kind. (Earlier this year, the U.S. joined Russia and China in opposing the creation of a monitoring agency on sexual atrocities.)

And so a UN resolution that should be a no-brainer becomes a non-starter.

To combat this way of thinking, Americans like me need to remind ourselves of some simple truths: The United States is one nation-state among many others. It is a political and legal entity, not a transcendent truth. And it has no monopoly on God’s purposes, which, however mysterious, would surely seek to help rape victims.

J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History and Chair, History and Classical Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares