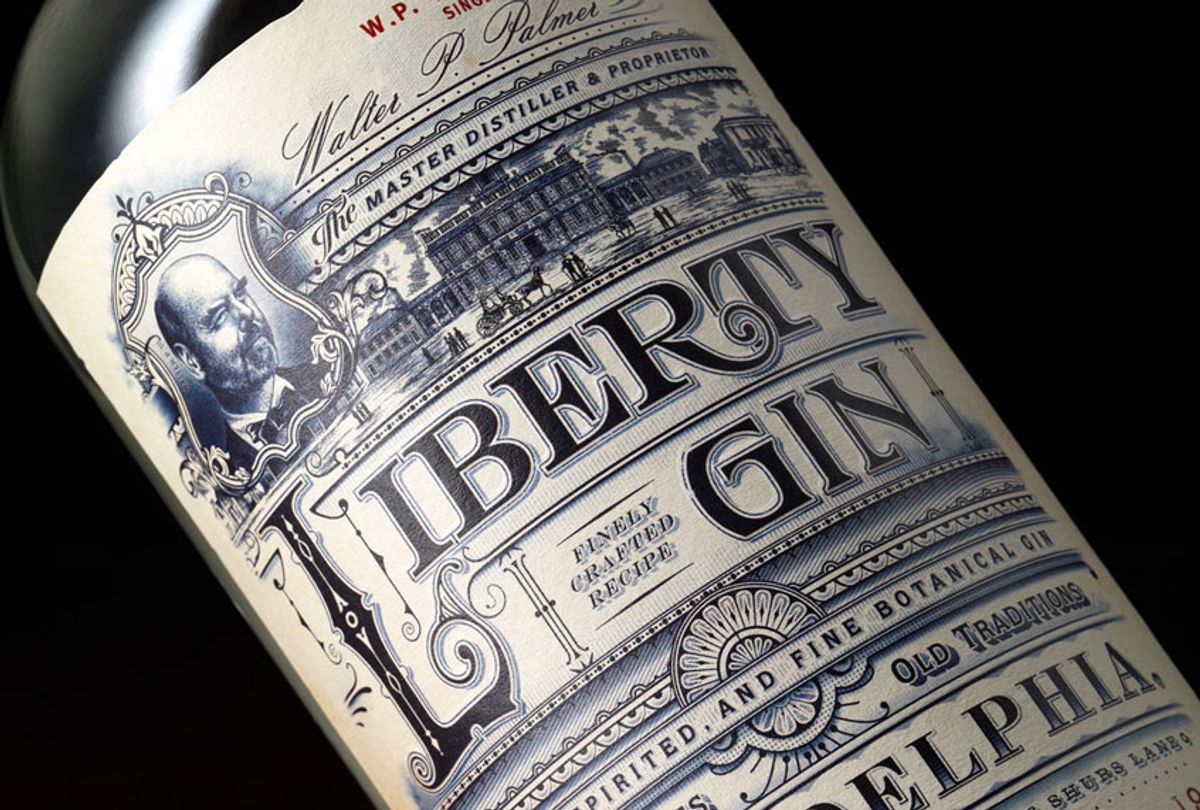

It's a unique experience to pour a drink from a bottle that has your friend's face on it. But my friend Walter Palmer has that kind of face. Gazing out from every bottle of his Liberty Gin, he looks like he could be a founding father, confidently gracing a piece of currency.

Walter doesn't fit my stereotyped image of a modern day maker. He doesn't have tattoos; he doesn't wear woolen hats indoors. We met back in college in Philadelphia. He was just a few years older than me, but already seemed to be the actual grownup I'm still waiting to become. He was definitely the only 22 year-old I knew who drove a Volvo and played Souza marches on his stereo. Straight from school, he went into the business world and worked there for decades, where he led a typical C-suite family man's life. "I had a job, I had a company car, I had a platinum American Express card and I did a lot of traveling," he recalls. "I made six figures. Everything was really great." Until it wasn't.

As he tells it, few years ago, "The board of directors changed, and I lost my job. My friends didn't talk to me. We didn't get invited to parties. We were literally ostracized. I was looking for a job, and bald white guys were not getting paid what they were getting paid before."

At this point, you might understand why a man would turn to alcohol, in a big way. But Walter didn't want to drown his sorrows in the stuff. He wanted to sell it. Reaching back to his art school background and drawing on his love of American history, he decided to get creative and reinvent himself — as a distiller. I remember having barbecue with him and his wife Katy when they came through town, learning the business by touring New York state distilleries. I had always known Walter as a gregarious host who could make a great cocktail. I'd had no idea he ever once entertained the idea of actually making the prime ingredients.

"When you have 30 years on a resume that basically is worthless," he recalls thinking, "you have to look yourself in the mirror and you have to say, 'What are my assets? What can I sell? How can I generate income?' I had to look at my core values, and that's honesty and history. I know this town. I grew up right outside of Washington's Crossing. I skate there. It's always been a part of me, that history. Nobody was actually in that space, and I thought I could be successful in there."

A good business requires a good story, so Walter set out to find one. "I would love to tell you I went to Amsterdam and searched through all these old libraries and read 18th century manuscripts," he tells me, "but I couldn't afford all that." Instead, he did what all of us do when we need obscure information. "I literally Googled it," he says. "Google Docs translated all these 18th century manuscripts. And the Dutch actually were very good at keeping the manuscripts for all these ships, because they were the ones that had the first global spice trade. So I took the ingredient list of what they used to call genever, which is basically the first gin, from 1780. We started to assign values to the ingredients, and to distill them. We did that well over 50 times with about nine tasters, using the same ingredients but in different values. We took about a year to kind of come up with that recipe. We settled on the same ingredient list, but in different proportions to the 18th century Dutch recipe." I am not in any way an expert on gin, but the final product is pretty damn marvelous.

Walter makes a convincing case for his beverage having revolutionary roots, even if negronis weren't part of any Declaration of Independence signing happy hour. "The Dutch spice ships had genever on them, and the Dutch were the major financiers of the American Revolution," he explains. "I know Washington had stuff in his boat to drink. My guess is somewhere, there was some genever, because the Dutch traded to Philadelphia. A lot of people would tell you that they drank beer and brandy. I'm sure they did, but gin is an old spirit and gin was here. We tell people that this is a flavor profile that our founding fathers would recognize." But, he adds, "We modernized it to what people today would actually recognize as gin, because if we drank 18th century genever, you probably wouldn't care for it. We dialed down the cardamon and we dialed up the citrus, which makes it more modern. They weren't making cocktails in 1770. They were just opening a bottle, because the water basically gave you dysentery." And once you're aiming a little higher than "dysentery-averse" in your beverages, you can appreciate the subtlety of a well crafted sprit.

The second part of Walter's story had to be a more 21st century American tale. "That was not my idea to put my face on the bottle," he says. "The designers said, 'We need to put some face on it.' People relate to that. They think, 'I met that guy.' Just about every person will ask the same exact question: 'How did you get into this? How did you start this?' At first I was ashamed of it, but now I just tell the truth. I can generally tell in a few seconds whether or not they want to hear the story of how I lost my job and I couldn't figure out what to do." And then, he says, "People want to be a part of somebody who has been roadkill and is actually making something. They like that. A lot of what we see in the media or in marketing in spirits, the story is not real. It's an ad agency creation of some fantasy of what a story is."

But Walter's story, like his cocktails, has a different twist. "It's okay that a bottle of gin I make this week is slightly different than the bottle of gin I made last year," he says. "We're not making Coca-Cola and we're not making Maker's Mark. We're making something that's really unique. These things are handmade. They have some level of honesty." And the secret ingredient is that element of mystery.

"What I figured out in my mind is that the power of a cocktail or a drink or a spirit is actually not what's in the glass," he says. "It's what is in the glass lets you do and become. It's a given that it's good. If it's not good, you wouldn't own it. But the real power of it is what it lets you do. It convenes you with friends. It rests you at the end of the day. It clears your mind. It relaxes you. It gives you the ability to join with other people in a good moment or join with other people in a difficult moment. That's the power of it. And that moment, in my mind, is the most important. The story reinforces that. This is made by that guy who's really gone through difficult times and it's important, and this moment is important. It's a very connected thing. To me, what's in the glass is kind of secondary. It's what the glass lets you do that is the most powerful. And teeing people up for that is my job."

And for a Philadelphian, the single word to attach to that experience was practically a no-brainer. "Frankly, everybody on the planet knows what liberty is and they have some idea of what they think liberty is," Walter says. "And the weird thing is, it's a thought, but it literally is a spirit. I sign bottles, 'Enjoy your Liberty.' I meet people and generally when I say goodbye to them, I say, 'Enjoy your Liberty.' And they stop and they're like, 'Wow, I'm really going to. Even if I don't have any gin, I can enjoy my liberty.'"

Even if you're not a big gin drinker, like me, Walter recommends a classic gimlet as a sophisticated spring cocktail.

1 part Rose's Lime

3 parts Liberty

Shaken over ice

Shares