Three bold numbers jumped out at me from the one-half page advertisement by the Stockholm Center for Freedom in the May 4 edition of The New York Times:

191 Turkish journalists are jailed, 167 are in exile and have arrest warrants out for them, and 34 foreign reporters are being targeted.

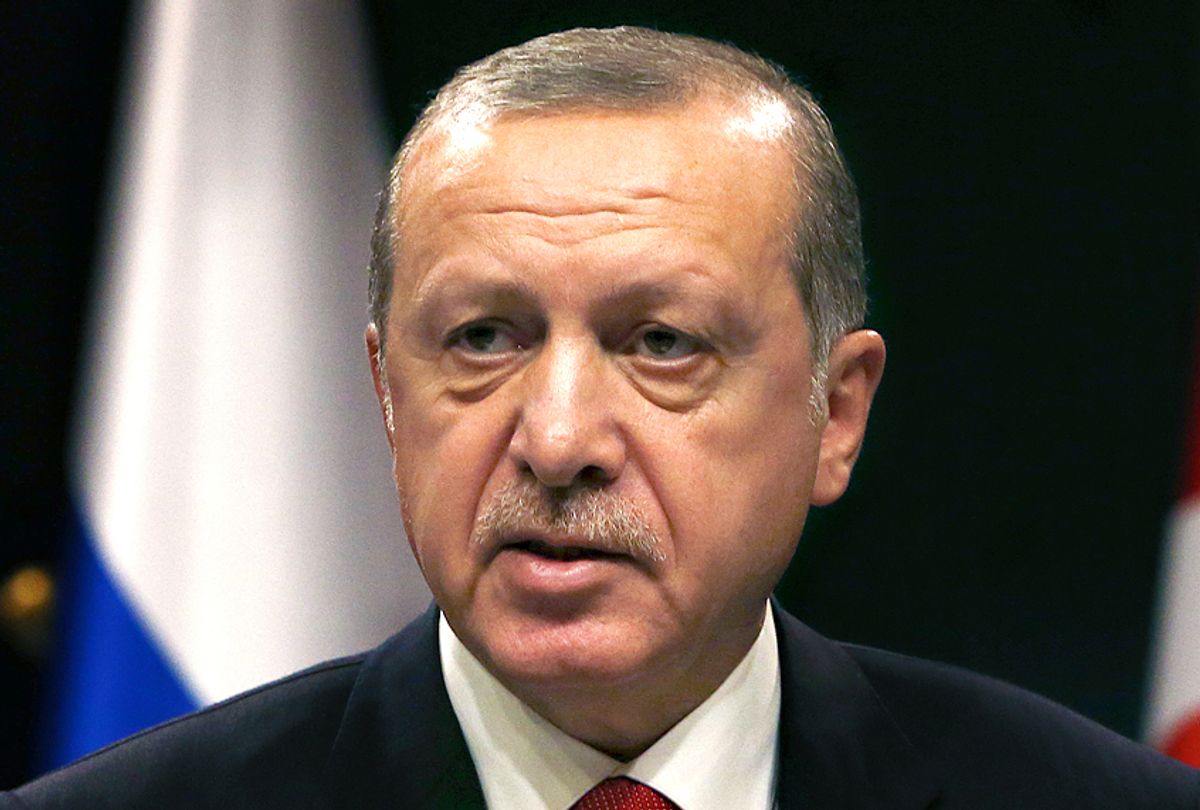

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has jailed more reporters than have all the other current dictators combined. No doubt, his friend in the White House, President Donald Trump, is applauding.

As Erdogan faces mounting political opposition in Turkey, so it is likely that he will go even further to muzzle the media. Just a few days ago, six journalists who had been freed on appeal were jailed again on so-called “counter-terrorism” charges.

Record press jailings

President Trump delights in calling journalists “enemies of the people.” His ceaseless war on mainstream journalism is encouraging dictators across the globe.

The number of jailed journalist globally now stands at about 250. The “World Freedom Map,” published annually by Reporters Without Borders (RWB) has been getting progressively darker – the number of violations in 2018 was 11% greater than five years earlier.

Many of the journalists imprisoned and intimidated today, from Azerbaijan to Egypt to Venezuela, have had the temerity to report the truth about the massive corruption in the governments of their countries.

Trump has just invited Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban to visit the White House. I do not think the issue of suppressing the media – Orban is a grand master – will be on the agenda.

Maybe I am wrong — Trump would like nothing better to hit the “fake news” press and ensure that Fox News, now his official propaganda organ, enjoys greater influence.

Where is the leadership?

For many decades, the United States was the active leader in its international diplomatic efforts to promote press freedom as a vital pillar of democracy.

Trump and his State Department are, by contrast, sharp and constant critics of the press. The result is an acute leadership vacuum.

European leadership ought to fill this space, but to a considerable degree it has been reluctant to go beyond cautious diplomatic comments.

Yes, German Chancellor Angela Merkel was swift in calling for a full investigation by Saudi Arabia for the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

To be sure, the Council of Europe is an important outspoken official voice of protest against the mounting harassment of reporters, but detailed reports have not had a major impact on the European Union’s Commission.

EU Commission’s role

Christophe Deloire, chief executive of RWB, looking at the forthcoming European Parliament elections, argues that the time has come to:

Make freedom of the press a core value of the EU, putting it at the heart of its treaties and institutions and at the forefront of today’s campaigns.

Tom Gibson of the Committee to Protect Journalists goes further in arguing that the issue of protecting journalists should be a priority for the leadership of the next EU Commission, which should develop:

a plan of action to build a favorable environment for independent and critical journalists.

The calls for EU leadership partly reflect concern that even dramatic events within the EU have not been able to secure effective and sustained Commission responses.

Murdered reporters

For example, there has still not been a meaningful investigation in Malta of the murder in October 2017 of journalist Daphne Galizia as she was investigating grand corruption in the Maltese government.

A report on Malta by the Council of Europe four weeks ago concluded:

Certain institutions, such as the Permanent Commission Against Corruption, have not produced concrete results after 30 years of existence.

Maybe Slovakia’s new President Zuzana Čaputová can influence the EU’s leaders. She surprisingly won election a few weeks ago on an anti-corruption/press freedom platform, which responded to the largest public protests seen in her country since the end of Communism.

Those demonstrations were sparked by the murder of Ján Kuciak, a 27-year-old investigative reporter and Martina Kušnírová, his fiancée. Kuciak was investigating alleged corrupt dealings involving some of the country’s wealthiest businessmen and the government.

European Green Party co-chairs Monica Frassoni and Reinhard Bütikofer have made protecting the press part of their European Parliament campaign, noting:

Press freedom is our greatest guarantee against corruption and abuse and must be defended at all costs to protect basic human and civic rights.

Daily news

Meanwhile, almost every day sees a report of yet another effort by a government to curb the press.

I hear quite frequently from Azerbaijani journalist Emin Huseynov who lives in exile in Switzerland. For a long time, he was striving to build public pressure to get his brother, Mehman Huseynow — also a journalist — out of prison in Baku.

Eventually, in March, after two years in jail, he was released, but the government has imposed a strict travel ban on him, as well as on other reporters. He could be arrested again at any time.

In Iran, Mohammad Reza Nassab Abdollahi, Editor-in-Chief of Iranian news websites Anar Press and Aban Press was jailed for six months in 2018 for allegedly “spreading false statements.”

Two week ago, he was arrested again and his websites were closed down. The government of Iran has given no explanation.

This article is republished from The Globalist: On a daily basis, we rethink globalization and how the world really hangs together. Thought-provoking cross-country comparisons and insights from contributors from all continents. Exploring what unites and what divides us in politics and culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. And sign up for our highlights email here.

Shares