It has become in vogue among millennials to mock the Baby Boomer generation as out-of-touch, reactionary, and complicit in destroying the planet. The media loves sensationalizing this purported generational divide. Business Insider recently published interviews with 21 different millennials explaining “why Boomers are the problem,” while Salon was early to the Boomer-millennial rivalry train. An Axios-SurveyMonkey poll found that 51% of millennials agreed that Baby Boomers had made things worse for their generation. Meanwhile, there are multiple Facebook groups devoted to mocking the oft-inane or offensive images that Boomers share on social media.

Though the media may play it up for clicks, the antagonism between the two generations is real — and unsurprising. Boomers, many of whom are parents to millennials, are not known for being computer savvy; a recent study found that Boomers were 7 times more likely to share fake news through social media compared to adults under 30. Likewise, many Boomers struggle to understand the cultural mores of millennials and Gen-Z, belittling us as "entitled" and "lazy." Yet it is understandable that Boomers would struggle to understand the millennial disposition: Boomers never suffered through a historic recession, nor did they come of age in an era of increasing income inequality, home prices and debt that has foreclosed the possibility of a middle-class life.

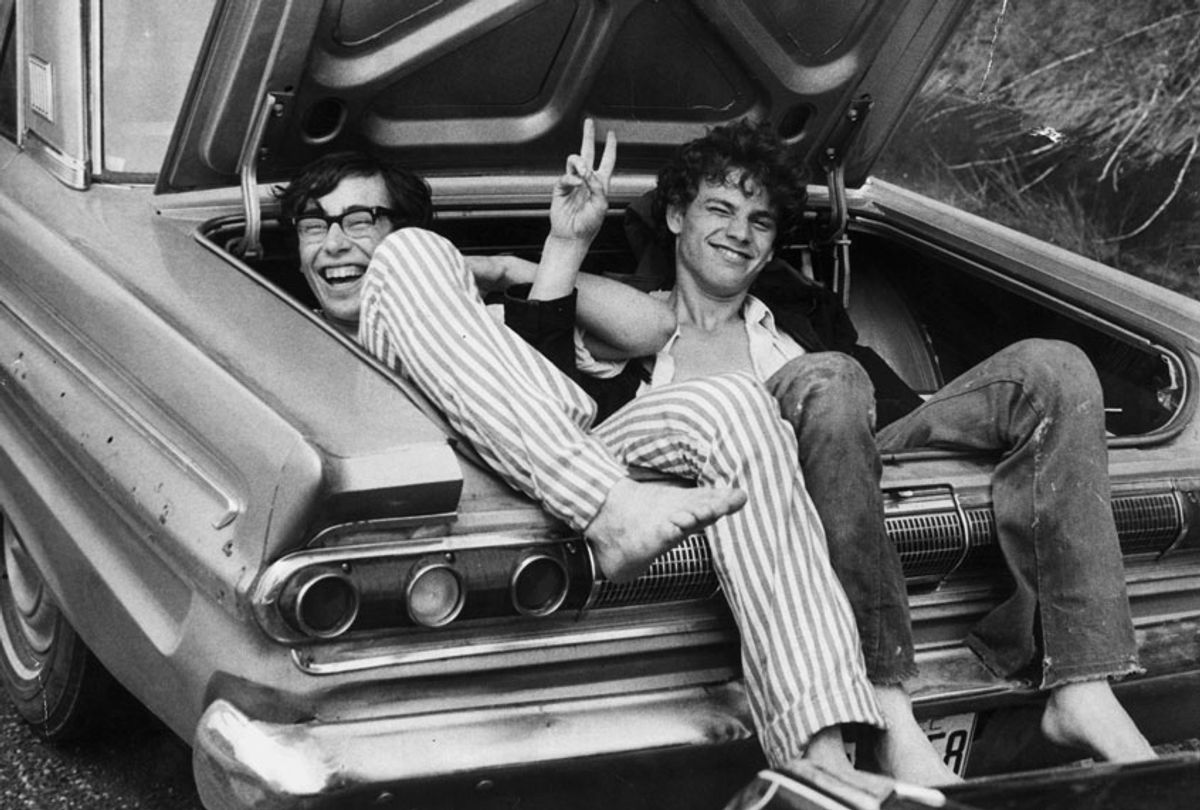

Yet there is a certain irony in the popular depiction of Boomers as out of touch, conservative, and entrenched in their economic interests. Boomers were, after all, originally the opposite: the counterculture generation — who lived through the Cold War, rejected the American imperialist experiment in Vietnam, stoked the civil rights movement, and spread liberal social ideals through music, art and culture — was largely comprised of Boomers. Arguably, the generation born between 1946 and 1964 were more radical than millennials or Generation Z: the Black Panthers, Young Lords, American Indian Movement, Students for a Democratic Society, and the Weathermen all were semi-militant Marxist groups who saw themselves as connected to a larger international socialist movement — and were, need I remind you, largely Boomer creations. The New York Times noted that there were 4,330 bombings in the United States between January 1969 and April 1970, more than one every day. Leftist millennials may have coined the term “woke,” but our politics are downright tame compared to our bomb-slinging parents’ generation.

Not all Boomers were, of course, hippies or leftists; a great deal hewed to their parents’ conservatism, and formed part of the “Silent Majority,” as President Nixon called his supporters. Still, the subset of activist Baby Boomers — the ones who self-identified as hippies and radicals, who rallied under anti-war banners and perhaps even participated in violent action against the government or corporations — are withering away and dying, while our generation reduces their existence to a punchline.

The millennial stereotype of Boomers, as computer-illiterate gullible reactionaries, is not only unfair but ignorant. It denies the radical political lessons that Boomers left for our generation, and which we and Zoomers have yet to learn. Specifically, there is a kind of anti-market, anti-capitalist mode of thought that hippies were particularly good at cultivating that could provide the key to a progressive future — and which my cynical generation has lost the ability to comprehend, largely because of the economic circumstances in which we were reared.

The Hippie Legacy

On my bookshelf, I have five volumes of course catalogs for the Mid-Peninsula Free University, dating from 1966 to 1972, which were passed down from my grandfather. Though only a few “Free Universities” or “Free Schools” still exist, the free school movement spread nationwide in the mid-1960s before slowly fading away in the 1970s.

The concept of a free school was simple: local community members could come together to organize to teach and take their own classes, generally for free (or a very small materials fee). Teachers were unpaid, and classes took place anywhere — houses, parks, community centers, sometimes at the beach. Anyone could apply to teach a class, and anyone could take a class. The goal was both to de-centralize the notion of school itself, and to challenge what the academy narrowly defined as knowledge.

The Mid-Peninsula Free University, situated in what is now called Silicon Valley, was one of the larger free schools in the country. And the course catalogs from that era provide a glimpse of what Boomers were thinking about, doing, learning and teaching at the time. Though some of the courses taught at the Free University were comparable to what you’d find in a community college catalog — photography or drawing classes, for instance — many of them are far more transgressive. The 1968 catalog lists courses on “Participatory Salad” (“A non-ideological approach to the preparation and consumption of salads, dressings, and related garnishments”), “Mind Unfucking” (“Religion--mysticism--music--nature--bacchanalian orgies--total recall with hypnosis + much more--timid souls welcome”), “Zen Beekeeping” (“We will discuss what beeing is”), “Experiment in Silence” ("Have you ever tried to communicate with your mouth closed? This course will be a weekend experiment in which all forms of communication except talking and note-writing are allowed”), “Yippie Liberation” (“With colorful clothes, bells, beads, incense and long hair we will flow through plastic stores, unfree universities, summer schools and other habitats of unliberated minds and bodies”), “Yelling at the Pond” (the course description is merely a poem about water), and — my favorite — “An Evening of B.S., Etc,” whose description goes:

An evening spent around the house BS’ing, drinking beer, wine, watching T.V., reading, relaxing, playing cards, etc. with whomever may be there. Intended to cure loneliness on Wed. evenings and to allow people to get to know each other under circumstances other than formal MFU course.

Even writing these out, I can feel my internal millennial scoffing and rolling its eyes. Growing up in an epoch of neoliberal economics and culture, millennials have been bred to feel that every moment of our lives must be monetized, or contribute towards future monetization, for our existences are so fraught and our economic circumstances so fragile. We lack the robust social safety nets, low tuitions and strong unions that undergirded the Boomer generation, and gave them the time to do things that weren’t relevant to their careers whatsoever: to sit around and “B.S.”, to yell at the pond, to experiment in silence, to ponder what bees are. These activities have no economic benefit whatsoever: they won’t make you a better worker, a more versatile employee. They’re just means of bettering oneself, waxing poetic, and pondering the world. There is a certain humanism at play here that millennials have forgotten — an empathy for other humans and animals, and the expectation of mutual goodwill. The hippies would probably have called it "love."

In a recent Buzzfeed News essay, “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” writer Anne Helen Petersen accurately describes why millennials have so much trouble “adulting,” to use a slur leveled at us by Boomers. Petersen traces millennials burnout to the way that we were raised:

As American business became more efficient, better at turning a profit, the next generation needed to be positioned to compete. We couldn’t just show up with a diploma and expect to get and keep a job that would allow us to retire at 55. In a marked shift from the generations before, millennials needed to optimize ourselves to be the very best workers possible.

Petersen explains how the millennial generation was the first that had been “trained, tailored, primed, and optimized for the workplace — first in school, then through secondary education — starting as very young children.” “Depending on your age, this idea applies to what our parents did or didn’t allow us to do (play on “dangerous” playground structures, go out without cellphones, drive without an adult in the car) and how they allowed us to do the things we did do (learn, explore, eat, play)," she writes.

The aftermath of this kind of childhood, one in which education and even leisure time were geared towards one’s future ability to be a laborer, had some detrimental psychological effects on us as kids. We millennials were taught that our ultimate purpose on Earth was to find what Petersen calls “The Job” — a dream job, the job that defines who you are as a person. “[Students] were convinced that their first job out of college would not only determine their career trajectory, but also their intrinsic value for the rest of their lives,” Petersen writes, observing how the culture of college campuses has changed:

Not until I returned to campus years later as a professor did I realize just how fundamentally different those students’ orientation to school was. There were still obnoxious frat boys and fancy sorority girls, but they were far more studious than my peers had been. They skipped fewer classes. They religiously attended office hours. They emailed at all hours. But they were also anxious grade grubbers, paralyzed at the thought of graduating, and regularly stymied by assignments that called for creativity. They’d been guided closely all their lives, and they wanted me to guide them as well. They were, in a word, scared.

I very much relate to this feeling, for I, too, am scared. And no matter how successful my career path is, I cannot stop feeling that way. I graduated from college in 2009, at the bottom of the trough of the recession, and applied to 60 jobs before getting the lowest-paid ($9/hr) and most distant one, a 50 mile commute from where I lived. I never made more than $20,000 in a year until I was 27, and never had a job I actually enjoyed until I was 29. In that time I had to defer and fend off $45,000 of student debt. I was almost always on food stamps. I kept a spreadsheet of every job I had ever applied to, now hundreds of entries long, to study how and why I was getting rejected. My twenties were largely miserable, so consumed was I with anxiety about school, work, debt, and networking: am I doing the right things to get my dream job? What if I’m not doing enough? What if this move, or this career choice, or this degree makes me less marketable or less attractive to employers?

The acquisition of a middle-class job — particularly one that I actually enjoyed, which I had been told, was the goal of life — was so searingly difficult that I felt constantly burned-out, even when I was unemployed. If someone had invited me to a course in Experiment in Silence, or to Zen Beekeeping, I would have chuckled. I had better things to do, things that might actually help me find a real career. That I can't connect to the hippie mindset is unsurprising in this regard.

The fact that millennials have trouble connecting with hippie culture also explains to some extent why the humanities are dying. The kind of philosophical reflection and humanistic thinking innate to the humanities aren’t applicable to the business world, at least not directly; they won’t get you a job unless your boss is a sympathetic former humanities academic. That our society has become increasingly supremacist about STEM skills, while mocking the humanities, seems to relate to our lack of free time, our obsession with work and with monetization.

As the Mid-Peninsula Free University attests, Baby Boomers were the last generation that was able to conceive of a world where capital didn’t govern all aspects of our lives. In-between Generation X found its rebellion in "slacker culture," rejecting the Reaganite yuppie work culture; millennials went the other direction, all-in on the workplace, as we were told since we were young that this was the purpose and function of our existence.

Hence, millennials often spend our leisure time on activities that will have the ancillary effect of making us money in some way, or making us more marketable as employees, or getting us closer to that dream career, or helping us stave off poverty. Consider social media, a near-universal hobby of my generation. Twitter may be “fun,” but I also know if I get enough followers, it can serve as a safety net if I get in an accident and need to raise money for medical bills. Instagram and Snapchat and TikTok are similar — in that having a great number of followers can help you sell your art, music, wares, crafts, whatever.

The near-universal desire to go viral — an impulse that drives many millennial artists — means that monetizing all aspects of one's existence has become normalized. Millennial DIY and “maker” culture is all about innovation and thrift, means of making oneself more economically self-sufficient. Millennial wellness and fitness culture is frequently synecdoche for self-improvement and career success. So much of what is popular among my generation is also an economic calculation, designed to make us better workers, or have more economic opportunity, or to serve as a safety net in place of the one that conservatives destroyed over the past few decades.

Millennials haven’t forgotten how to live without monetizing our existence. Rather, we never knew how to in the first place. There has never been a social safety net for us, at least not one of much import; unions haven’t been widespread, college costs are so prohibitive as to put many of us in debt bondage, public housing is nonexistent and Obamacare is a flawed "free market" solution that fails many.

My greatest fear for my generation is that in the process of forgetting how the hippies thought, we will forget that love is crucial to any actual progressive-left movement. You can see the seeds of this in how online discourse around politics happens: those on the opposing side are castigated as irredeemable. Yet a truly progressive vision of the future has space to redeem those who are bigoted in some way, recognizing that they became so in part because the right has gotten to them first; worse, the left never showed them comparable compassion, nor sought to truly understand the material underpinnings of xenophobia and bigotry in a way that could connect to those who had been ensnared by hatred.

This is how politics may die if we forget the lesson of the Boomers. A lack of love and an inability to perceive the world except in marketable terms will doom any left-progressive movement. The hippies may have grown complacent and reactionary in their old age, but they were right, at least, about the need to cultivate a counter-culture that opposes the mainstream culture engendered by capitalism. We cannot envision a post-capitalist future if we do not first experience it among ourselves; if even our leisure activities are centered around monetizing our existence, there is no hope for an alternative.

Shares