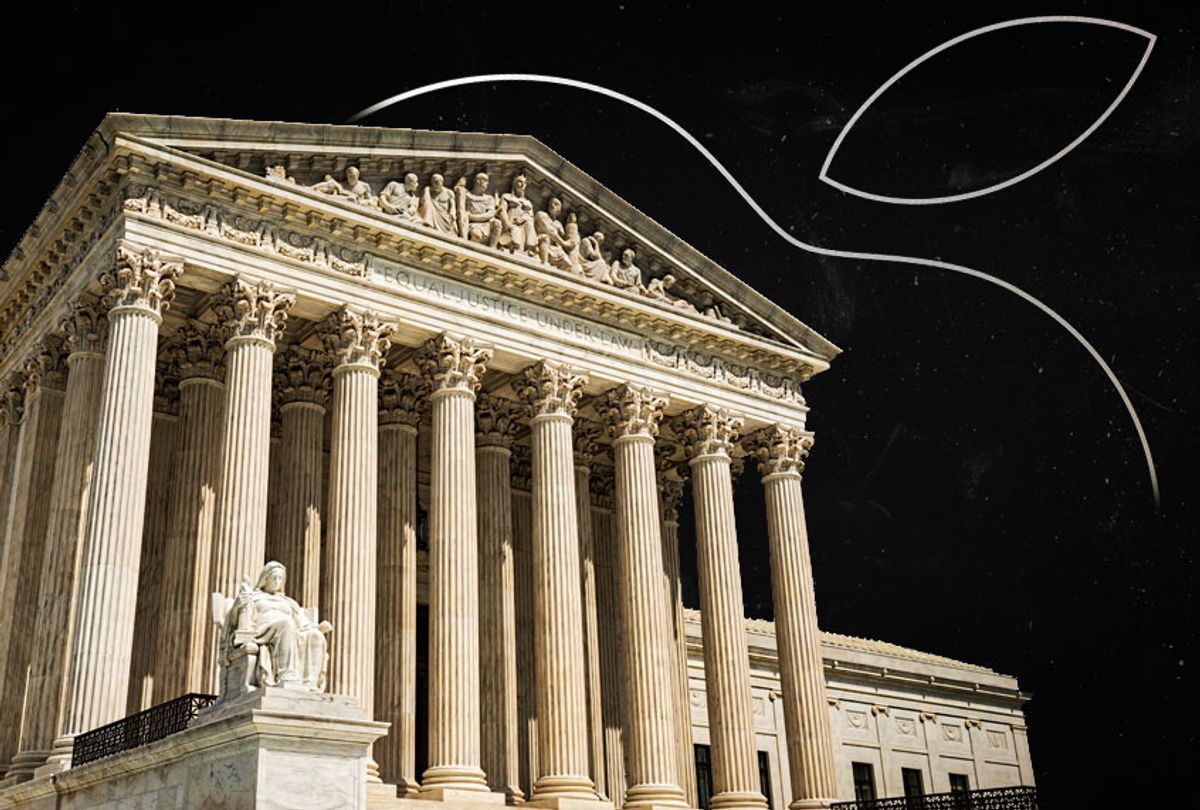

With Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh, an appointee of President Donald Trump, joining with his liberal colleagues, the Supreme Court ruled a group of iPhone owners engaged in a class-action lawsuit against Apple should be allowed to move forward with their case.

Alleging its App Store amounts to a monopoly, the plaintiffs claim Apple is violating antitrust rules, according to CNN. The origin of the lawsuit can be traced back to 2011, when iPhone owners launched a class-action claim on the grounds that app developers were raising their prices since Apple took a 30 percent cut in sales. Since Apple does not allow customers to download apps from anywhere other than its own iTunes App Store, the plaintiffs argue this violates their rights as consumers and runs afoul of antitrust legislation.

In a decision joined by the court's four liberal judges, Kavanaugh argued the lawsuit should be allowed to proceed, because "that is why we have antitrust law." He also argued that if "retailers engage in unlawful anticompetitive conduct that harms consumers," those consumers have a right to seek redress for their grievances.

The judges also dismissed Apple's attempt to toss out the lawsuit on the basis that iPhone owners have no grounds for suing, because Apple is an intermediary. "Apple's line-drawing does not make a lot of sense, other than as a way to gerrymander Apple out of this and similar lawsuits," Kavanaugh wrote.

"A claim that a monopolistic retailer (here, Apple) has used its monopoly to overcharge consumers is a classic antitrust claim," Kavanaugh continued in the decision. "But Apple asserts that the consumer plaintiffs in this case may not sue Apple because they supposedly were not 'direct purchasers' from Apple under our decision in Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U. S. 720, 745–746 (1977). We disagree. The plaintiffs purchased apps directly from Apple and therefore are direct purchasers under Illinois Brick."

He added, "At this early pleadings stage of the litigation, we do not assess the merits of the plaintiffs’ antitrust claims against Apple, nor do we consider any other defenses Apple might have. We merely hold that the Illinois Brick direct-purchaser rule does not bar these plaintiffs from suing Apple under the antitrust laws. We affirm the judgment of the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit."

It is important to note the court has not sided against Apple regarding the merits of the antitrust case; it has merely stated the case itself should be allowed to proceed. If Apple loses, however, it could have major ramifications for the technology industry.

"If a court rules that Apple has an unlawful monopoly, it could require Apple to pay out hundreds of millions of dollars or even change its App Store model," wrote Adi Robertson of The Verge in June. "If the Supreme Court upholds the Ninth Circuit’s decision, though, it will just send the case back to a lower court, where the fight will keep going."

Robertson added, "But the decision will also affect how much power consumers have over digital platforms. In 1998, a major appeals court ruling shot down concertgoers who sued Ticketmaster for driving up ticket prices, saying that Ticketmaster was actually selling distribution services to concert venues. The Ninth Circuit’s opinion explicitly says that decision was wrong. So a favorable Supreme Court ruling wouldn’t just keep this particular lawsuit alive. It could make other powerful online stores — or, in Reuters’ less-charitable estimation, 'toll-keepers' — more accountable toward their users."

Shares