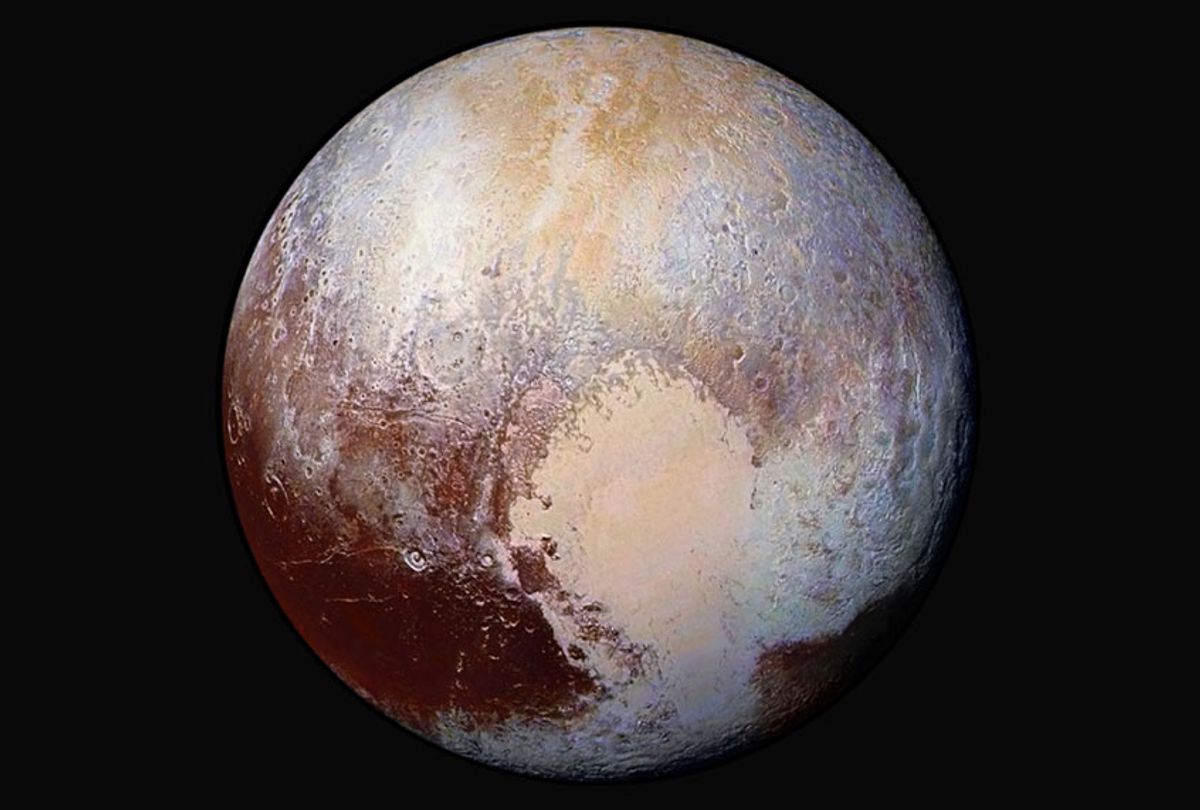

Prior to 2015, scientists knew little about Pluto — mainly because it is quite dim and small from Earth's perspective, not to mention 4.67 billion miles distant.

However, when NASA's New Horizons space probe flew by the far-away dwarf planet, imaging it in unprecedented detail, the historic mission raised more questions than answers. For one, the probe's findings raised suspicions that some of Pluto's mountains were formed on a bedrock of water ice.

According to a new study published on Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience, computer simulations provide compelling evidence that an insulating layer near the surface is keeping a subsurface ocean from freezing beneath Pluto’s ice. In other words, there could be a liquid ocean on the planet.

A team of Japanese scientists published the study, proposing that such an otherworldly idea is possible because a thin layer of ice containing trapped gas molecules, known as gas hydrates, at the bottom of the ice shell could be insulating the ocean. By calculating Pluto’s temperature and the thickness of the ice shell, scientists concluded the gas hydrates would be enough to maintain a subsurface ocean.

“We show that the presence of a thin layer of gas hydrates at the base of the ice shell can explain both the long-term survival of the ocean and the maintenance of shell thickness contrasts,” the authors wrote in the study. “[Gas] hydrates act as a thermal insulator, preventing the ocean from completely freezing while keeping the ice shell cold and immobile.”

In the paper, researchers suggest that the gas hydrate layer is likely methane, which means it could have evolved from the material that created Pluto in a specific chemical reaction.

“The formation of a thin [gas] hydrate layer cap to a subsurface ocean may be an important generic mechanism to maintain long-lived subsurface oceans in relatively large but minimally heated icy satellites and Kuiper belt objects," the authors wrote.

Understanding how a subsurface ocean can exist on Pluto will provide scientists with invaluable information to better understand how similar bodies of water can exist on other planets, too.

"Liquid water oceans are thought to exist inside icy satellites of gas giants such as Europa and Enceladus and the icy dwarf planet Pluto," they said. "Understanding the survival of subsurface oceans is of fundamental importance not only to planetary science but also to astrobiology."

Scientists have been repeatedly surprised and bewildered by the data New Horizons has collected and processed from its flyby in 2015. New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute said in a statement last winter that the diversity of Pluto’s landforms “rival anything we’ve seen in the solar system.”

“If an artist had painted this Pluto before our flyby, I probably would have called it over the top — but that’s what is actually there,” Stern said.

The initial photos showed unexpected complexity of the dwarf planet.

“The surface of Pluto is every bit as complex as that of Mars,” said Jeff Moore, leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging (GGI) team at NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field in California. “The randomly jumbled mountains might be huge blocks of hard water ice floating within a vast, denser, softer deposit of frozen nitrogen within the region informally named Sputnik Planum.”

And now we might know why.

Shares