It’s spring, and in America’s state capitals legislatures are winding up their business and, too often, bringing out the padlocks.

All 50 states give the public the right to see government records and documents, but many state legislatures are weighing changes in their open-records laws.

These changes rarely end up making our government more transparent. Instead, lawmakers often try to conceal public records from the people who own them — that is, you and me.

Public records laws exist to allow us to see into the decision-making of our government. When bureaucrats make efforts to obscure our view into their actions, it serves only to undermine government officials’ accountability.

It also diminishes the public’s understanding of, and faith in, democracy.

Making what’s public a secret

In Massachusetts, lawmakers are making it harder for the public to see elected officials’ financial disclosure statements.

In California, the legislature has been considering the shuttering of records that could reveal misconduct or conflicts of interest in publicly funded research.

Last year, Washington state lawmakers rushed through a bill that allowed them to hide lawmakers’ calendars and email exchanges with lobbyists. Only after public outrage erupted over the move did the governor veto the measure.

Most efforts to hide public records aren’t as brazen.

Here in Oregon, our once-robust disclosure law, passed in 1973, is now pockmarked with more than 500 exemptions, many chiseled by bureaucrats wishing to avoid scrutiny or lobbyists seeking to protect their clients.

Oregon officials can conceal investigative evidence of wrongdoing by medical professionals — not just doctors but also dentists, veterinarians and undertakers. Basic information about birth, marriage and deaths is locked away. The pest-extermination industry won a special exemption to keep secret information about bedbug infestations. Oregon’s once-solid disclosure has become so flimsy that it once allowed state officials to declare it was a confidential trade secret to reveal the location of lightning strikes.

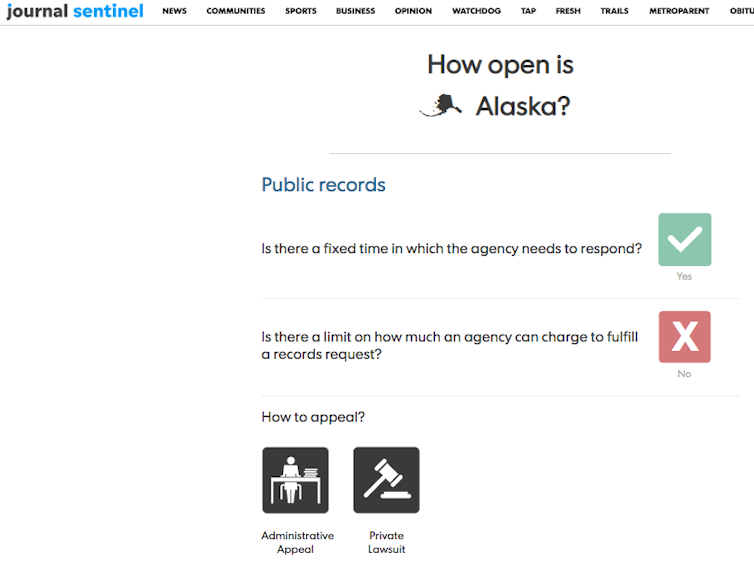

Journal Sentinel screenshot

The right to know

The fight over public access to government documents has often involved the mundane grist of government, such as studies and budgets and memos and emails.

This tension over what’s called the “right to know” debates back to the country’s founding.

“A popular government,” as James Madison wrote to a friend, “without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or perhaps both.”

I spent 30-plus years as a journalist and editor, focusing on investigative reporting on the state and federal levels. I’ve filed hundreds of requests for documents and now teach journalism students to do the same. And I believe the best way to protect these laws of transparency is to put them to use — and show the public why they matter.

In 1966, Congress passed the Freedom of Information Act, the first law that required all federal agencies to make documents public when asked. But in some ways, state public-access laws that were passed as post-Watergate, good-government reforms have a greater role in our everyday lives.

What the Defense Department has in its files may be of national import, but it can be just as powerful for a community to find out what the local zoning board — behind closed doors — is planning for a city’s neighborhoods.

Using your rights

Journalists do perhaps more than anyone to advertise the power of these laws.

A study looking at more than 30 years of news stories found that almost all investigative reporting relies on government documents, and nearly half of investigative reporters make a point of telling readers these disclosure laws played a role in prying records out of government’s grip.

ProPublica screenshot

Researchers, advocacy groups and businesses are among the most common users of these laws, but anyone can write out a request and hand it to a government agency. (In a pinch, I once scrawled a request on the back of a reporter’s notebook. It worked.) Today, in most states, public officials must work under a deadline to respond to the request.

And that’s when things can get difficult, because officials have three big ways to block your access to the public’s records.

One is fees. State laws allow government to make you pay for the records, although many have provisions to reduce or waive these costs. In most cases, government can charge only for the actual cost of retrieving, reviewing and copying documents. But those costs can still be high enough to thwart inquiry.

Another method is delay. Most states have deadlines under which agencies should hand over records, but the waits can range from fewer than 21 days in states such as Vermont and Rhode Island to more than 100 days in Arizona, Mississippi and the District of Columbia. The wait for federal records under the Freedom of Information Act can take much longer — sometimes years.

The third way is through more exemptions. Some debates are not easy.

The Florida legislature recently passed a bill that would prevent disclosure of photos, audio or video recordings of mass shootings, such as the 2018 shooting that killed 17 students and staff members at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland.

Supporters say that this exemption could prevent further trauma. But others argue hiding these images makes these tragedies sterile and makes them more likely to occur. The availability of these kinds of images later helped news organizations hold police and school officials accountable for failing to do more to stop the Parkland shooter. The South Florida Sun Sentinel won a Pulitzer this year for its reporting that held those officials accountable.

Records belong to you

In recent years, a rise of public-records watchdogs, such as Muckrock, has made filing public records requests easier while shining a light on government efforts to close off records. The Student Press Law Center offers a public records letter generator.

Journalists are writing about government efforts to hide documents — a move that properly puts the heat on government officials and increases their own transparency by showing readers how journalists go about doing their jobs.

News outlets in Atlanta banded together to expose the mayor’s secret effort to defy the Georgia public records law. The stories led to a criminal charge against the mayor’s press secretary for improperly withholding records embarrassing to her boss.

“Public records are public because they belong to you — you and other taxpayers paid to create them and, of course, you paid for all the work they record and represent,” Kevin Riley, editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, said during the unfolding scandal.

“So no one should be looking for ways to keep them secret from you.”

Brent Walth, Assistant Professor of Journalism and Communication, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares