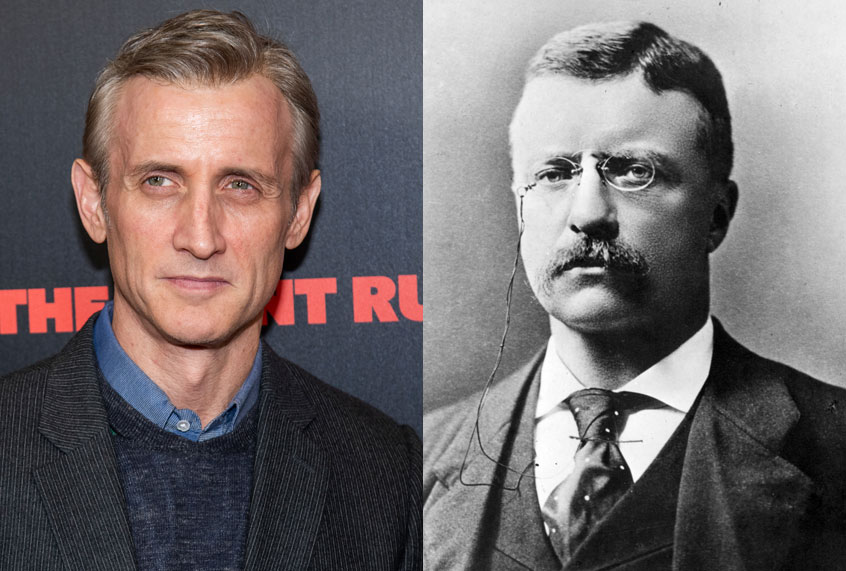

If you’re a fan of presidential history — and, in particular, the kind of arcane presidential trivia that makes for great dinner-table conversation — then the work of Dan Abrams, the chief legal affairs anchor for ABC News, is a good match for you. Last year he released “Lincoln’s Last Trial: The Murder Case That Propelled Him to the Presidency,” which told the fascinating story of a murder trial that Lincoln handled as an attorney before he became one of America’s most esteemed presidents. He visited Salon Talks last year to discuss that one.

Now Abrams has a new book, “Theodore Roosevelt for the Defense: The Courtroom Battle to Save His Legacy,” which like his work on Lincoln also covers a mostly-forgotten presidential trial. Whereas Abrams’ book on Lincoln discussed a trial that occurred before a president took office, however, his Roosevelt book covers a trial that took place after his administration ended. The impetus was a civil suit against Roosevelt by William Barnes, a New York political boss who claimed libel when the former president accused him of being corrupt. Even as Roosevelt fought to preserve his reputation, he also found himself compelled to address one of the most important political issues of his day — namely, the brewing conflict in Europe which would later be known as World War I.

Salon spoke with Abrams about his new book, his impressions of Teddy Roosevelt and why he believes the latter is both similar to and different from our current president.

What made you take an interest in writing about famous trials involving future or former presidents Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt?

I think with the Lincoln book it really stunned me that there was this transcript out there of the only case that Abraham Lincoln had argued. I couldn’t believe it when my co-author actually came to me and said, “There’s this transcript out there, it’s the only one that exists on the Lincoln trial, only discovered in 1989, almost no one has written about it.” I said, “Come on. You’ve got to be kidding me.” That’s what initially spurred the interest, and that partnership between David Fisher and myself, and as a result of that we decided, “Let’s see if there are any other interesting somewhat forgotten transcripts out there of great trials.” That led us to the Roosevelt one.

Setting aside questions about the merits of that case itself and looking solely at the power dynamic between Teddy Roosevelt and William Barnes, who would you say was at an advantage?

Well, I mean look. I will say this. They had to change the venue out of Albany, New York, because Barnes would’ve been at an advantage in Albany, where he was the king. So the trial was actually moved to Syracuse because there was a concern that you wouldn’t be able to get a fair jury for Roosevelt in Albany. When looking at it in a more macro picture, I think that Roosevelt was still one of the most famous people in the world, one of the most influential. He was still regularly called to weigh in on events leading up to World War I. His words mattered. In that context, I think it’s only fair to say that Roosevelt was more influential than was Barnes. But to be clear, Barnes was a major power broker in the Republican Party. While Roosevelt was a post-president, Barnes was still in the middle of his reign as this trial went forward.

In a way you’re looking at, a hundred years ago, a situation in which celebrity is an actual form of currency in terms of wielding power. To what extent does it have limits?

No question, and when Roosevelt made his comments about Barnes — calling him corrupt, calling the party corrupt, etc. — he knew his words would resonate because he was the former president of the United States, and people knew who Theodore Roosevelt was. I think that he was well aware — he was I would say one of the first presidents to truly appreciate the power of the media and the power of his celebrity.

With celebrity there are also questions of honor, and that is an area that distinguishes Roosevelt from, you could argue, contemporary politicians — the premium that he placed on honor. Yet even though he was worried this whole trial would destroy his reputation it’s become a footnote today. Do you think that says something about how we view the concept of honor 104 years later?

I think it’s more how we view controversy. When we’re in the heat of a controversy, it feels like everything, and that exists today. There’s some political fight or some legal story or whatever it is and the country’s following it. Everyone thinks this is the biggest story, but the truth is that the controversies weren’t necessarily what resonated years later. I think this was a great example of it. This was a story and a case that was on the front pages of papers around the country every day for weeks. It was the talk of the country, certainly the talk of New York, but well beyond New York as well. As I say in the introduction, I think anyone in the courtroom would’ve felt like they were sitting through the trial of the century. Yet the fact is that it became quickly forgotten — even Edmund Morris, the great Roosevelt biographer, relegates it to a little chapter in one of his books and almost pooh-poohs it — except for Roosevelt, it was very important.

He updated his summary on “Who’s Who” to include this one other trial as a significant moment in defining who he was. He devoted more space to this than to the Panama Canal in his “Who’s Who” summary. It’s a long way of saying I think that it takes on less significance historically, but to Roosevelt and to people who are in it at the time it really matters.

I’d like to segue from your comment just now to the issue of foreign policy, because that’s another parallel between the era in which this trial took place and the era we’re in now, where we’re discussing issues of America’s role on the world’s stage as an international power. Roosevelt at this time promoted the idea of America becoming involved in World War I, did he not?

He did, he did. What’s interesting is it actually intersected with the trial, meaning when the Lusitania was sunk in the middle of the trial, the immediate thing was to call Roosevelt and get quotes from him. His concern was that there were German Americans on the jury who would not view favorably to Roosevelt talking about how this was further evidence of the need to get involved in the war. Yet he still went out there and made public comments echoing his view that we needed to be much more aggressive with the Germans.

Would you say that the foreign policy vision of Theodore Roosevelt in that era also foreshadowed the role that America plays in world affairs today? Because this wasn’t a one-time thing in terms of Roosevelt advocating a more aggressive role for the United States. He was arguably the first president to push what would now be considered a blatantly imperialistic agenda. Personally, I would place it one president before him, at William McKinley, but he was very much an advocate of that. Do you think he would have been happy with how events turned out over the next century?

Well, look, I think they’re separate questions, and I don’t view it as imperialistic that Roosevelt turned out to be right about the Germans. I think that’s a separate question from talking about the Philippines and Spain, etc. I think that when it comes to World War I, the legacy of Theodore Roosevelt is he was right and that [President Woodrow] Wilson was too soft based on what was to come. I’m sorry, I’m not really answering. Your question was —

No, I appreciate that these are very complicated issues, because Roosevelt in other respects was absolutely an imperialist. Where do you draw the line between someone being an imperialist and someone being perceptive?

And again, your word is “imperialist,” and I appreciate it and I understand why you used that. There’s no question he had an aggressive view of foreign policy and the United States’ role in it. I think that in terms of your question, what do I think he would think of where we are now? Look I think there are a lot of comparisons people make between Trump and Roosevelt, and I think some of them are spot-on and others are completely false.

I think that on something like the Iran deal, Roosevelt would have taken a lot of time to figure out the costs and benefits of any kind of deal. I don’t think that he simply sought to make decisions on foreign policy based on how it would seem or sound and on how his base would view it. He took, as you said, his honor and his reputation incredibly seriously, and his legacy. I think all of that weighs into how he made decisions on foreign policy.

Do you think that honor, reputation and legacy influence Trump in the way that they influenced Roosevelt?

No. I don’t think that President Trump thinks about those issues anything like the way Roosevelt thought. Rectitude was incredibly important to Roosevelt, and I think that that’s one of the reasons that this case happened. He was so furious because he felt like they were cheating on the other side. He felt like people weren’t getting to decide for themselves who their elected officials should be. He felt that it was just an insiders’ club and he wanted more representation for the people. It wasn’t for his advantage, he wasn’t doing it to benefit himself. He was doing it because he truly believed that it was in the best interests of the country.

Earlier you said that some parallels between Roosevelt and Trump are spot-on. I’m seeing “New York Republican celebrities.” Are there other parallels in your opinion?

Sure. Theodore Roosevelt prosecuted the media. He had a love-hate relationship with the media. He actually used the Department of Justice to prosecute media organizations that he didn’t like because they said things about him that he felt were wrong. You had him insulting opponents, mocking them, calling them eunuchs at times when he talked about his political opponents. He was known as autocratic. I think Morris once described it as, “convinced of the rightness in his own decisions.” I think there are definitely comparisons there and, look, when you see a sitting president being sued — Donald Trump is involved in a number of lawsuits now that may not conclude by the time his presidency is over.

Do you think Trump will have been as transformative a president as Roosevelt? Because most students of history would agree that whether you like or dislike Theodore Roosevelt, he was a transformative president.

I think that’s true. I think he was transformative. It’s hard to know. I am not a true historian. I am an appreciator of history, who has come to become an expert on particular moments in history, and so I don’t know what the Trump legacy will be in terms of [being] transformative. I think that there is no question that there are aspects of what he is doing that will be looked upon unfavorably. I think the way that he treats the law, and some of the other issues that I care about enormously, are concerning. And that’s not policy, that’s based on really words that he’s used in undermining institutions that I care about. But we’ll see.

To play devil’s advocate, many of Theodore Roosevelt’s critics when he was president accused him of being, as you put it, autocratic. How do we distinguish between a genuine autocrat and partisan hyperbole?

Yep, that’s a good question. There are gradations there, and look, I think you can make an argument that when it comes to executive power, that [Trump and Roosevelt] share that — that they both believe enormously in executive power and that they both have somewhat autocratic tendencies. There’s no question. I think that’s a very fair comparison. But that does not mean therefore Trump and Roosevelt are similar. I think that there are certain aspects of Roosevelt that Trump would admire in his unwillingness to give in to opponents —his seeming disregard for what the other side had to say on a variety of issues, his use of insulting words to demean those on the other side. With that said, I think that Theodore Roosevelt would have had some very serious concerns about what Donald Trump has been doing and saying.