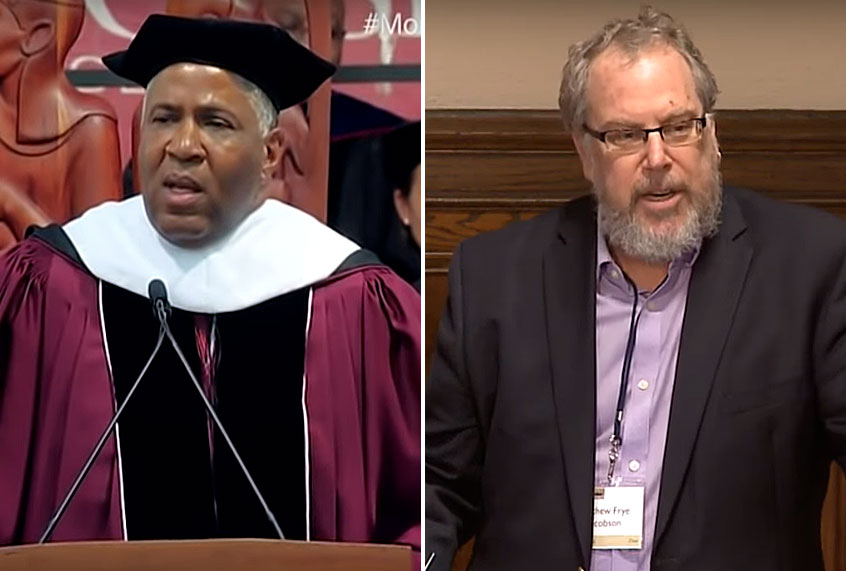

Nobody needed to wait for billionaire Robert Smith to relieve the student debt of this year’s graduates of historically and proudly black Morehouse College to know how heavily higher education has indebted millions of students for years now. It wasn’t always this way, and we can’t rely on a few rich people to relieve it. To understand what’s at stake for democracy as well as for individual students, the Yale historian Matthew Frye Jacobson conducted this conversation with me just before the 2015 upheavals on some American college campuses were spotlighted and condemned, as part of the long conservative crusade to rescue liberal education from liberals.

I’ve assessed that crusade often in Salon, but here I offer a critically supportive understanding of colleges riding political and economic currents that are transforming their institutions and their students.

The interview was conducted for the Historian’s Eye Project. Here’s the interview, on audio and in transcript.

What follows is a transcript that’s been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Matthew Frye Jacobson: We don’t have to go very far to find someone talking about the crisis in higher education. Are you one of the people who feels a sense of crisis, and if so, what is the nature of the crisis?

Jim Sleeper: “Crisis” is a slightly more dramatic word than the one I would use. I would call it an unsettling sea change. And the two sea changes I understand are, No. 1, the precipitous underfunding of higher education by the public is shifting its costs onto students as individual consumers. So instead of having liberal education develop citizens or humanists, it becomes a careerist, consumerist transaction: I pay and take on debt, so I’d better get a “good” job. And higher education becomes reduced to that. That to me is a sea change.

The other sea change is precipitated by the larger, structural and cultural shift that creates a shift from citizen to consumer. That’s going on in the larger society so much that students are coming to college already with that consumerist, careerist mentality.

How would you track these changes across time, in terms of your own observations?

I think they’ve been going on for a longer time than people are now asserting. When I taught at Queens College from 1977 through ’79, these kids were working from job to home to school. They were exhausted, and they had a very instrumental attitude toward their education. And the number who I would describe as idealist — there’s a bit of that in every kid, and that’s what you’re reaching for, the humanist, the citizen — have always been driven by tremendous pressure. What I sense has changed is that the people running the institutions have changed their metrics, their measures, of what’s good.

First of all, the faculty are more and more “free agents,” in terms of a casualization of the academy [meaning the increasing use of part-time adjuncts instead of full-time professors]. That leads to people thinking less in “communitarian” or humanist terms and more like rats-in-a-maze, consumer-market terms. You can call it “free agent,” but there’s no more collegium — a college as a self-governing body of scholars that’s maintaining certain traditions, partly against or in response to the outside world. That’s been replaced by not just the casualization, but the atomization of faculty. I think that has intensified. People come in with ideological agendas that may not be consumerist, but they’re narrower agendas. I’m a civic republican, and I think the old colleges should nourish that.

Have they in your lifetime?

When I was an undergraduate at Yale in the late 1960s, that spirit was still there in Kingman Brewster, in the university chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, a well-known activist, and in old guys on the faculty who felt themselves as the keepers of the flame of the collegium, the “company of scholars” in a non-bureaucratic, non-commercial sense. Whatever you thought of their views, they felt themselves to be keepers of the conscience of the collegium. They believed in this collegium, in arguing with opponents in a constructive way, not just scoring points or polarizing.

It is true that we get a little rosy in our nostalgic memories, but there has been a sea change. It’s like a tide that begins running out and is rushing out. It’s not even perceived as a crisis, because people are so much immersed in it. They’re being carried along by it. There’s a lot of sleepwalking going on.

You’re pointing to some really complicated and dynamic relationships between the university on the one hand and the wider culture on the other. How would you narrate this, in terms of causes and the way these changes roll out over time: Is the university merely reflecting broader changes in the culture, or is there something specific to the university itself that’s feeding back out into the culture — some of these careerist or instrumental attitudes?

In the undergraduate colleges, I think it’s reflection rather than proaction. But at the research universities, some of the research scholars come in already evangelizing for a more corporate business market-oriented approach to everything.

You see that coming from the scholars.

I think the economists, from Milton Friedman and before, were progenitors of this national cultural ethos, homo economicus uber alles — to mix languages and metaphors. That came from the university, not that there wasn’t a lot of receptiveness to it everywhere, as in, What’s good for General Motors is good for America.”

Certain sections of the universities have been progenitors of that cultural shift. They are now so lavishly funded by outside, non-academic interests that it becomes hard to tell the chicken from the egg. We have centers, institutes, virtual think tanks, that are cranking out this stuff under the imprimatur of universities. It’s funded by people who are eager to harness “scholarship,” in quotes, to produce what they want. And certainly in scientific research, there’s a big scandal going on. I’m not saying that that’s true at Yale, but the research is predetermined or overdetermined, paid for by the pharmaceutical companies and others.

However, at the undergraduate level, I think colleges are the victims and not the generators of this cultural sea change. Their attempt to uphold the humanist ideal may have been hypocritical and weak, but it was not so devoted to the markets. A combination of conservative free-marketeering and neoliberal, “world is flat” global economics is transforming collegiate liberal arts education, not the other way around.

“Victimization” is a really interesting formulation. Victimized by who or what? Is it state legislatures?

Was Adam victimized when Eve gave him the apple, or was Eve victimized by the serpent? Somebody was the tempter, the proactive initiator, and it wasn’t the colleges. Of course, there was always rightly a sense of their indebtedness to, and being of service to, the workings of the larger society.

I’m asking who’s on the other side of that knife. Is it state legislatures? Is it the kids coming through the door into the institution, having been primed by their schools and college counselors to insist on a certain kind of a product, not even education?

It’s the equation of consumerism with a BA. “What’ll the degree get you?” Every kid at 18 comes in after 5,000 hours on the internet and 5,000 hours in the shopping mall, I don’t literally mean those numbers, but unless they went to very unusual schools, they’ve already been inundated by a consumerist society.

Every college teacher knows what it is to encounter kids who have to be sort-of awakened — and I don’t mean “woke” in the simpleminded sense. You have to blow on a little spark that is still there, ignite it, get it to come to life. And I feel that college teachers have always faced that challenge. [Former Harper’s editor] Lewis Lapham once wrote that in the 1950s the average Yale instructor had an indulgent smile on his face because he knew that his job was to put a veneer of Western civilization on “the expensive furniture that was on loan to him from Westchester and Long Island: ‘Here’s where you’ll be spending a lot of money. Here is London. Here is Paris. Here are the Medicis …’”

There was always that feeling that the kids were coming to us already overdetermined. But you always reach for more in every class, you spot the three or four who haven’t been foreclosed by a careerist endgame. And their minds are opening.

One critique has always been that scholars are given the wrong set of incentives as teachers. They become “narrow specialists” who lose sight of the fact that the kids they’re teaching are not about to become apprentices to their methodology. You’re trying to open their minds to the world. And it is true that the way ladder faculty work, there are some disincentives to good teaching: If you’re going to be a real scholar, you’re not going to spend as much time teaching undergraduates. But I think that scholarship has been co-opted toward narrower market ends or “scientistic” ends, as in the game-theorization of political science, which used to be more about the grand and tragic questions of politics …

So I see the two sea changes. On the level of the culture of the kids, I think it’s worse than it was 30 or 40 years ago. The 18-year-olds that came in then were more literate and a little more open to non-market things, but it depended on the time and the group. At the teaching level, I think the incentives have gotten more perverse.

Can you talk about the governance of the university? You’ve not been shy in some of your critiques of the university in general. Can you talk about some of the issues that have mattered to you?

I do insist that the model of a university faculty as the collegium — again, a “company of scholars, not in the sense of a corporate, shareholder company but of a group of people who keep alive the light of humanism and scholarly pursuit — thrives best in a republic, a civic republic, but it is not subservient to it. It serves it by being itself, by being slightly independent. And it is the independence of collegiums that has given universities their dignity and capacity to contribute something original to markets and states. So if it’s a private university, the job of the trustees should be to keep the lights on — a metaphor for providing good facilities and raising money — and leave the collegium to determine the rest in the model of the university as standing slightly apart.

So you have to find these weird creatures called trustees who, on one hand, are usually creatures of the market, because they have the wealth and know how to raise it and manipulate it to keep the endowment up. You have the tension that they are supposed, at the same time, to have such fond memories of what liberal education was in their youth, and so much concern for the republic, which is not just a consumer paradise, that they’re willing to give some of their time and wealth to the capital campaigns and the endowment in order to keep the rest of us free. And we give them our gratitude and our respect if they do that.

Lately, trustees and university presidents have tried to take the collegium on these rides into market riptides, as I showed here in Dissent in 2012.

Yale did that in founding a new liberal arts college in a joint venture with Singapore that has Yale’s name on it. There’s a burgeoning new market of rising young Asian middle classes, and Singapore wants to stem its brain drain. Some Yale trustees were private investors in Singapore’s sovereign wealth funds for 20 years before Yale went there. So I think they have taken the collegium on a ride.

And at the same time, the financing that kept public universities somewhat apart from markets has been decimated. The University of Wisconsin at Madison used to be 45% funded by the state legislature of Wisconsin. Now it’s funded 15%. So they’re all out there with their tin cups.

At the University of Virginia, the Board of Visitors — the trustees — wanted the university to get big into MOOCs and into things that they believe in, because algorithmically-driven, market-driven metric models was the way to go. They hadn’t thought through the pedagogical or curricular implications. They tried to fire a president who was resistant to it. And there was a revolution from the collegium. The students, God bless them, rose up, and they said, no, we’re not here just to surf these market riptides. We’re here to stand slightly apart.

People call that ivory tower elitism, but it’s not. It’s something that Thomas Jefferson recognized was essential. That’s why he founded the University of Virginia, to cull an aristocracy not of blood and wealth but of talent and virtue. That’s what these colleges are supposed to be doing, nurturing civic-republican citizen leaders, in my view. And the governance structures don’t exactly crush that, but they are seduced by the siren songs of markets.

George Pierson, the former historian of Yale, said to Lewis Lapham that universities are like little boats in a current. Some of them are trying to tack this way, and some of them are trying to tack that way, but they’re all being carried toward the waterfall of market fundamentalism. Pierson was a conservative saying, we’ve got to watch this consumerization. It’s in a great, long essay by Lapham, called “Quarrels with Providence.” It ran in the Yale alumni magazine just before 9/11. He had interviewed him in the 1990s.

So can the mission of the university withstand these market pressures? Is there more to say about a tug of war between educators and non-educators for the soul of the institution?

Well, that goes back to our governance question, too. I think that’s what the faculty was trying to do when it passed a resolution expressing grave concern about Yale’s Singapore venture. The faculty, if it chose to, could still assert itself enough to resist some of these pressures. It gives a rubber stamp or pro forma approval to heavily-funded centers that are eviscerating the scholarly structures in favor of more market-oriented or national security-oriented programs.

I’m not a big defender of the old disciplinary departmental “silos,” as they’re called. I don’t doubt that there should be a reformation of liberal education outside of narrow disciplinary fiefdoms. I would like to see a reassertion of faculty power in senates and collegium-type modes that would reform what’s rigid in the old departmental structures but also stand up to and rebuff this proliferation of semi-scholarly, think tank-like centers and institutes — so that at Yale we’ve had kids studying with Prof. David Petraeus or Prof. Stanley McChrystal or Prof. Tony Blair. Come on!

I believe that if the faculty could rise up and resist that, it would still be felt. It was felt at the University of Virginia. The trustees backed off. Even here, after the faculty passed that resolution opposing a lot of the Singapore venture, it didn’t stop the venture, but three months later, [Yale president Richard] Levin announced his resignation. There may have been other factors, but clearly, that was something. Faculties still have that residual power. The question is, do they still understand themselves as the bearers of that responsibility and power?

Which then gets back to the question: Do you see the mission of the university surviving this moment?

It’s partly dependent not only on the possibility of re-stoking faculty will, but on exogenous things. If, for example, there was another market collapse, or some huge foreign policy crisis, this could reformulate people’s assessments of the neoliberal paradigms, metrics and parameters within which the bad changes are now taking place. I think we’re sleepwalking into this stuff because those paradigms and practices are so dominant. Liberal education says that the world isn’t flat; it has abysses that open suddenly, and you have to have a language and ability to cope with that. I hate to say this, but it would probably take the opening of a new abyss beneath the floor of neoliberal conventional wisdom for the university to recover its ability to stand apart.

People who care about universities should be on the lookout to help reframe people’s understandings. I don’t think that the conventional wisdom that has been so dominant in our students’ and colleagues’ minds is going to last. But whether it will be replaced by something even more Orwellian, I can’t say. I don’t think it’s within the power of universities as governing polities or as institutions to singlehandedly change that. I don’t see that. But there could be moments of resistance or reconstitution of universities in reaction to these changes that might give them new leverage.

I’m interested in the relationship you see between the mission of the university and the state of the republic, and you’ve talked about that in a lot of different ways.

If you follow Allan Bloom [the University of Chicago intellectual historian who wrote “The Closing of the American Mind“], there’s a tension between the university and the republic. Liberal education’s job is to question, not just facilitate. But a republic needs loyal citizens, myth-makers, all the adhesives. I think that a balance can be struck between providing society with narratives and adhesives, and remaining skeptical and asking questions rather than just knee-jerk facilitating whatever is dominant.

Some people within the university will become mythopoeic creators of the new narrative of a national or political, coherent destiny. People need those things. We’re never going to get away from the need for that. But there will be others who will always try and break that down, and that, I think, is healthy, that tension between those two functions.

But in policy terms, if you could make a few tweaks and adjustments and implement new policies here and there, what might reverse, or at least change, the course that we seem to be on?

On the level of sustenance of funding, I would definitely reverse the proportions of public funding, get it back to 80% from the legislatures for the public universities. And in the private universities, if I could wave a magic wand, I would have more disinterested donors, the people who were so sentimental about the old college that they give millions without putting any strings on it. I would disappear the people who come sweeping in to fund institutes with agendas. So, more disinterested private philanthropy for the privates as well as the publics. And the publics, since they don’t have as many wealthy donors, they need the legislatures to rethink what they’ve been doing.

Can the public, as you see it, be retrained to think again about education as a public good? Or has the sun set on that?

Well, that goes back to our larger question of what’s happening to the general political culture. If you see the United States today as a republic in which only “consumer sovereignty” and shareholder value are the measures of what is good, and if people go on believing that the Invisible Hand of markets will work out all the rest, then there’s no way of getting people to rethink education as a public good, because they will continue to think of it only as, ‘How do I get my career? How I take on this debt and pay it off?’

And if that’s the weight of the logic of society today, so that we don’t have people thinking for the good of the country, how are they going to think of the good of education, the good of the republic? If we’ve gotten to the point where inequality deepens, and crises with the rest of the world deepen, it becomes everyone for himself, sauve qui peut. And that’s what I see happening. The number of people who, out of civic generosity, think that they can enlarge or ennoble their selves by giving their energies to a good larger than themselves? Well, there are still a lot of people like that in America. But I think they’re under increasing strain.

How do you account for that?

I think it’s the increasing, accelerating power of for-profit-driven, casino-like financing and the increasingly intrusive and intimate nature of consumer marketing. It’s practically groping us in our entertainments, our news programs which are run by for-profit corporations to bypass your brain and your heart and go right for your lower viscera, because that’s what gets to your wallet. That’s what glues your eyeball to the screen, gets you to watch the commercials. Some of us can remember assailing trashy commercialism in the ’60s, but the “counterculture” became the over-the-counter culture. It was capitalized upon and marketed, and market forces just absorbed everything in this protean way. They even began to market Black Power, you know, niche marketing. They’re perfectly comfortable with marketing anything and reducing it to a commodity.

And then changes in the structure of capitalist governance itself, in which this algorithmically-driven vision of shareholder value drives corporate managers. They lose their jobs instantly if they don’t go for the quarterly bottom line, which means they cannot make socially rational decisions, which means that their marketing is implicitly degrading of reflection, personal virtue, whatever.

I have to give people credit for being as good as they are these days. Lately, a number of my former students who have been 10 years out of college come circling back to have dinner. They say, “Well, I clerked for a federal judge. That was OK. Now I’m at a white-shoe law firm and, my God, it’s empty.” Or, “Now I’m at CNBC as a producer for Jim Cramer and it’s empty …”

And they come back to me as if I had an answer. So I think that’s a straw in the wind, that there’s a dissatisfaction. Who can focus and generate something from that? That was what we thought Obama was doing in his 2008 campaign — giving voice and direction, so we thought. Turns out he wasn’t enough of a counterweight.

Occupy Wall Street was a bottom-up reaction to that failure. It didn’t have enough leadership or paradigms. So I don’t know how you get people to think about the public again. What I do know is that it may seem implausible, politically, at any given moment, but it’s irrepressible. So, you get the Tahrir Squares, no matter how they turn out. Or you get what’s happening in Hong Kong. They’re going to lose — the Chinese government’s not going to give an inch. We’re waiting for a new myth, a new paradigm, new leadership, a new political philosophy or political strategy.

Is teaching, in some ways, an antidote to all of these things? When it’s you and your students in the classroom, do you feel that you’re able to address these kinds of things in a meaningful way?

Yes. I think the combination of the readings and discussions brings out this side of the kids. It gets them asking these questions, and it does breathe a little oxygen onto that spark. The evaluations that they write say that. But my experiences is that five and 10 and 15 years out of Yale, they’re unhappy. They have a divine discontent. Let’s put it that way.

The number that are really pioneering great solutions — well, there are some. But it’s hard to say. One of my students became the digital director of Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign, but now he’s out marketing his data mining techniques to corporate buyers. You know, he’s making a great living. He got Obama re-elected by doing stuff that we don’t approve of, all this data mining and surveillance and intrusive matching of people with “friends” to get them to recruit them to vote for Obama. You know? He believed in Obama. He used to get teary-eyed about Obama. But now look what he’s doing.

There are always the kids who are just headed for Goldman Sachs and they believe in it, and they think they just have to indulge me. But there’s a lot of kids in between, and I like sowing those seeds of divine discontent. That’s what liberal education has always been since Socrates. You hope you’re not going to be asked to drink the hemlock, but you’re going to go on sowing these seeds of divine discontent, because that’s what makes them citizens and not just consumers.