General Wei Fenghe, China’s defence minister, surprised the world over the weekend.

In a speech at Singapore’s Shangri-La Dialogue — an annual Asian security defence summit — he said the Chinese government made the “correct” decision ordering a military crackdown on the student-led, pro-democracy protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989:

That incident was a political turbulence and the central government took measures to stop the turbulence.

Then, on Monday, the English-language Global Times newspaper, a mouthpiece of the communist government, ran an editorial further defending the June 4 Tiananmen massacre:

As a vaccination for the Chinese society, the Tiananmen incident will greatly increase China’s immunity against any major political turmoil in the future.

The June 4 crackdown has been one of the most sensitive and taboo subjects in China over the past three decades. So why is the government now justifying the brutal military violence against unarmed citizens in such an open fashion?

A harsh crackdown and immediate denial

The Chinese government has good reason to worry about open discussions about the Tiananmen crackdown. The 1989 pro-democracy protests were one of the largest and most peaceful social movements in modern world history. The students and other participants did not take violent actions or put forward radical demands. They simply appealed for the government to reform itself.

The protests involved over a million students and other citizens in Beijing (as well as other cities), but were so peaceful and well-organised that the protesters did not smash a single window along the capital’s streets during seven weeks of demonstrations.

The moderate wing of the CCP at the time, led by General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, accepted the movement as “patriotic” and the demands for reforms as legitimate.

The moderates supported the principle of “resolving the issues on the track of democracy and rule of law” and conducted conciliatory discussions with the protesters. They were also prepared to allow greater press freedom and independence in China, loosen the constraints on civil society organisations, and tackle corruption in the government.

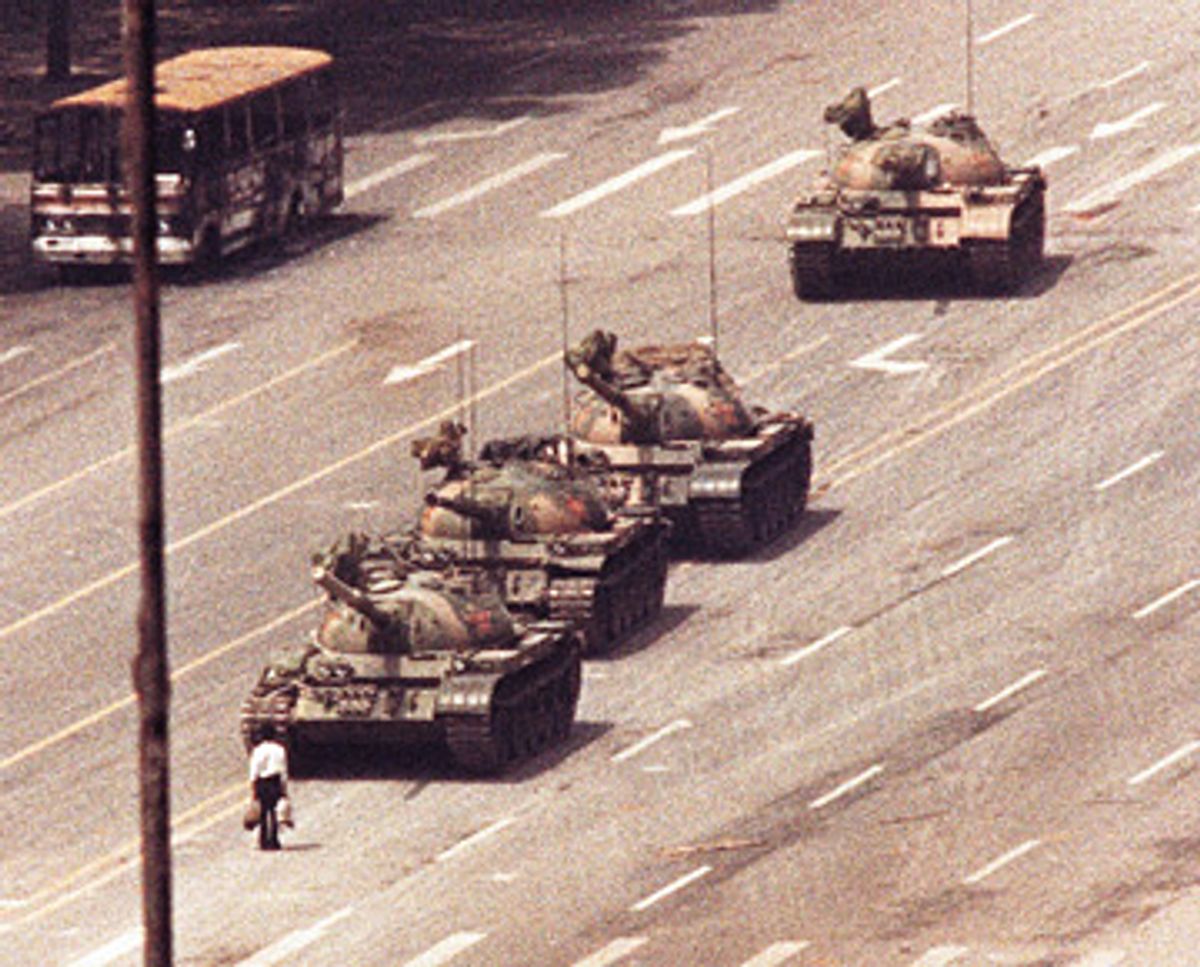

It is a shame the hardliners, led by Army Chief Deng Xiaoping, dismissed Zhao and his followers and sent over 200,000 soldiers equipped with machine guns, tanks, cannons and helicopters to take lethal action against the protesters, resulting in the death of hundreds of innocent citizens, if not more.

The order to shoot civilian citizens was so shameful that most soldiers defied it to reduce casualties. And despite two to three months of propaganda attempts to praise the soldiers as heroes, the CCP and Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) later altered its description of the event from the “pacification of a counter-revolutionary riot” to the “Tiananmen disturbance” or the “Tiananmen incident”.

The Chinese government has also banned any discussions of the subject in classrooms, in print and online. This attempt to erase history prompted one author to call China the “People’s Republic of Amnesia.”

Whitewashing of history

Wei’s comments in Singapore and the Global Times editorial reflect the party’s longstanding line on the crackdown.

During and right after the military response, the CCP regime constructed a narrative that portrayed the peaceful protests as a conspiracy of hostile forces backed by Western powers to create turmoil and divide China. The government justified its crackdown as necessary for maintaining stability, paving the way for China’s rise and eliminating “the thought trend of bourgeois liberalisation”.

It also launched a comprehensive and sustained “campaign of patriotic education” to indoctrinate students from kindergartens to universities with this party-approved narrative, omitting any inconvenient facts.

Today, students are either taught nothing about the Tiananmen massacre or told the protesters were criminals. Some Chinese students in my university classes in Australia have even refused to consider readily available information about the event after several years of studying abroad.

Worse still, many Chinese immigrants coming to Australia after 1989 share the same wilful ignorance.

In the modern world, repressive authoritarian rule is not a necessary condition for economic development and prosperity, and never should be. All stable and well-developed economies around the world are liberal democracies, including Australia.

The rapid economic growth in China over the last four decades did not result from the communist dictatorship, which condemned China to utter poverty for 30 years during the Mao Zedong era. The primary factor contributing to China’s rise was the evolution of the country from a totalitarian society to a more open one. This allowed for more personal autonomy and greater exposure to globalisation, including the transfer of capital, technologies, skills and new ideas.

Indeed, when the Tiananmen massacre took place, few could imagine the CCP regime would last another three decades, let alone become a superpower second only to the United States in economic and military might.

However, as a “fragile superpower”, China is mired in a host of problems. These include systematic corruption, environmental degeneration, loss of public trust in government, enormous wealth inequality, burgeoning debt, and growing tensions between “stability maintenance” and the defence of human rights. Despite the government’s soft power moves abroad, the world also remains suspicious of its actions in the South China Sea and initiatives like One Belt, One Road.

The government’s defence of the 1989 crackdown demonstrates a paranoia that a “colour revolution”, or another popular uprising, will someday come to challenge the regime.

One can only hope this insecurity becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy and the zeitgeist of the June 4 generation is one day breathed back to life.

Chongyi Feng, Associate Professor in China Studies, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shares