Hanna-Barbera's first cartoon debuted in 1957. In the 60-odd years since that moment, Hanna-Barbera's characters and series, including the Flintstones, the Jetsons, Scooby-Doo, and so many others are now beloved across generations and by people all over the world.

On the surface these are "just" children's cartoons, but many of Hanna-Barbera's cartoons are rife with double-entendres that only become more obvious and clear when viewed through adult eyes of an adult or other more sophisticated viewers. The enduring popularity and widespread love felt for the Hanna-Barbera cartoons has created an opportunity to subvert expectations by using those characters and settings to tell more challenging stories about such topics as human nature, family, love, sex, religion, capitalism, greed, war, and politics.

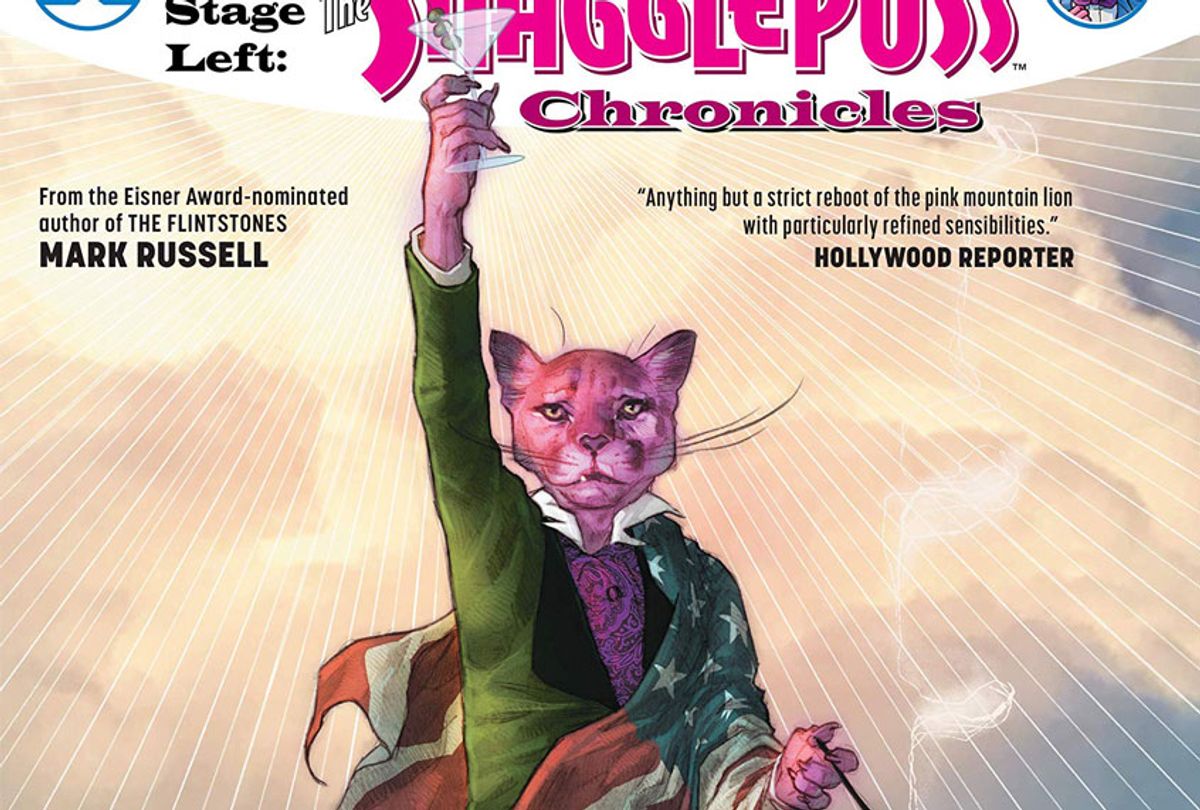

Mark Russell has taken on this challenge to great effect and creative success in his DC Comics graphic novel series "Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles," which features the titular Hanna-Barbera character as a gay icon and playwright in 1950s New York. Along with other characters such as Quick Draw McGraw and Huckleberry Hound, Snagglepuss navigates life and love as a member of the gay community during the reign of terror that was the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Red Scare.

"Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles" won the 2019 GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Comic Book. "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" has also been nominated for best limited series at this year's prestigious Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards.

In this conversation Russell reflects on how he managed to write such a humane story about vulnerable people and their struggle for equality, as well as the ways in which "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" is a rebuttal to the Age of Trump and the rising global tide of fascism. Russell also shares the principles that motivate his writing and character-development, avoiding stereotypes and gay tropes in fiction, and the challenges and rewards that come with living a life of principle.

Mark Russell is also the writer of DC Comics' reimagined versions of "The Flintstones" and the ongoing series "Wonder Twins." Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

"The Snagglepuss Chronicles" is very sincere and humane. It is very personal. Were you writing to someone? Who is this for?

I don't think I'm just writing for one person. But I do think that in a lot of ways you always write for a small audience. You write for yourself and you write for maybe one other person who's experienced something with you. So, yes, you do tend to write for a specific audience, whether one understands that is what we are doing or not. For me, writing is inherently an act of sincerity. Every advance I've made as a writer has been a rebellion against insincerity. With "Snagglepuss" and "The Flintstones" before it, what I really tried to do was be as blunt as possible with myself and in my writing.

How do you manage that vulnerability? And why are so many writers and others afraid to be that vulnerable in their art and lives?

It takes a toll on you. I mean there's only so much you can do before you feel completely exhausted. "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" was the hardest thing I've ever had to write, not because the task itself was that difficult but just because it was so emotionally devastating to build connections with these characters, and then having to do horrible things to them, to expose their own truth.

How did you make that decision to do it? Was there a moment where you said to yourself, "I can't do this. I won't do this."

No. I think that once you commit to that path as a writer, you have to see it through to the end. Story ultimately needs to emanate from the characters in a way. That the characters you create — you understand their backstory, you think about what it would be like for them. It's really an act of empathy, of understanding what it would be like to live in a world that they lived in, in ways we do not normally see in popular media. What would it be like to live in a world behind the scenes from the cartoons and the other ways in which we've gotten to know these characters through popular culture? You build the story from there.

For "The Snagglepuss Chronicles," the two pillars that I built that story around were, first, I know that he is a gay icon. Second, Snagglepuss has a background in theater, because all of his catchphrases such as "Exit stage left," "Heavens to Murgatroyd," they're all theater references.

That got me thinking about why Snagglepuss would have left theater in the first place and also what it would have been like living as a gay man in New York during the 1950s, before he got into the cartoon. The whole story just builds itself upon those two basic assumptions.

With Snagglepuss and the other gay characters such as Quick Draw McGraw and Huckleberry Hound, how did you avoid the tropes which are all too often used to write about gays and lesbians in fiction?

I try not to think in tropes at all. I try to think about how this is the character as I see them and this is the other character that they are going to be interacting with. What would be a natural way for these two characters to relate to one another? And what would the results of their story be? I might actually end up being close to a trope in the story. You mentioned the tragic gay figure who kills himself. That doesn't feel trite or lazy to me, if it emanates naturally from those characters' motivations and their interactions with the other characters. Ultimately, I don't think too much, either in terms of trying to follow a trope or avoiding one. I just try to write what feels natural to the moment and creating this character's journey.

Given how humane and authentic "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" is — like your previous work in "The Flintstones" — what are the principles that guide your work?

The principle I operate from is that everyone deserves to be taken seriously. I think that once you take a character seriously, once you try to see them as they see themselves, then even if they're despicable, they will come across as nuanced and human.

How does having cartoon characters exist in the "real world" — without having the human characters even make note of that fact as something odd — create storytelling possibilities?

On one level it is abstract because I am writing a universe that the reader does not belong to. So there is that distance but at the same time the characters are human beings in their souls that the reader can relate to.

Online and elsewhere you are very clear about your politics. How is "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" speaking to the age of Trump?

In a lot of ways "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" is about our global flight into fascism. The book is about when people are afraid and they feel like they're in peril then the natural instinct — and what is an incorrect one — is to ostracize outsiders. We begin to engage in the "othering" of people who aren't like us, because we're afraid that someone is coming to get us. We always have to be vigilant against the people who use that fear for their own purposes. And I think that's ultimately what my "Snagglepuss" graphic novel is about. I think that is also what is happening in this country right now with Donald Trump and what he represents.

"The Snagglepuss Chronicles" is a very literate book. Given the setting of the Cold War and the 1950s Red Scare, were you signaling to the blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, or others like him?

Not Trumbo specifically, although Snagglepuss does break the blacklist the way Trumbo did. More specifically, Snagglepuss was based on Tennessee Williams, both in terms of his back story being a Southern gothic playwright and also living as a gay man in New York.

There is a line of dialogue in the graphic novel where Snagglepuss says that the difference between being a star and an actor is that audiences want to be a star — the star is aspirational — whereas the actor, especially on the stage, is a mirror, a lens, for looking into yourself. Where did that wisdom come from?

In many ways "Snagglepuss" acts as my manifesto on art, my own critic looking inward at myself and my feelings about past projects. Where I felt I failed in my journey as a writer was usually when I was trying to sound like someone, to be something else, rather than just learning to sound like myself, to say what I actually think. I'm aspiring to create art that is better than I am. That is where I've failed in the past. It is only once I've given into my own thoughts and fears and began to write about them that I feel like I've really matured as an artist. In "Snagglepuss" I wanted to put that in stage language, for theater actors, and the difference between being a star, someone to whom others may aspire, and an actor who is more like an accurate reflection of who they are.

Is there any specific moment when you knew that you had to improve as a writer?

Well, luckily, most of my really, truly epic failures happened before I was getting published. Luckily the reading public has been spared. I go back and read a lot of this old work now, and I'm just embarrassed that I ever wrote it. I am also glad at the same time. The only way you grow as a writer is living like you are close enough to the sun that you see potential in yourself but not so far away that you get discouraged. You can't be in love with your work to the point where you feel like everything that drops from your pen is gold. But you can't be so discouraged by your inadequacy as to give up. The writers I know who ultimately create good art fall somewhere between those two extremes.

Many writers and other artists have to confront and overcome impostor syndrome. Has this been your experience?

I confront it on a daily basis. My biggest advance as a writer was giving in to that, realizing that, "Yes, I am an impostor, and it's OK." I'm writing through the eyes of an impostor and as long as I'm true to what I'm feeling and thinking then it's okay. To borrow a phrase from Cheryl Strayed, "I've embraced my own mediocrity," where I write about the failings and inadequacies of myself. I've given up on trying to be like Charles Dickens or some other writer that I would have aspired to be at one point. I now just allow myself to tell the stories that make sense to me.

Is Snagglepuss a hero?

Snagglepuss is a hero because he did the most daring thing that a man in his position could do back then. And that was simply to live. He chose to live his life in a way that made sense for him, and that felt authentic to him. I think ultimately that's what every act of heroism is. It is an act of authenticity. It's an act of stepping out of the roles and expectations that other people have for you and doing something that feels right to the voice within, that inner voice.

I think that too much of our lives is spent acting on incentives — and the incentives are usually for us to shut up and do as we're told and to go along with things that we don't necessarily believe in. That benefits us in the short term.

Snagglepuss is a hero because he chooses authenticity. He steps out of the incentives that have been laid out for him and chooses something that makes no sense on a purely instrumental immediate level. But his decision allows him to be true to the core of who he is.

A vast majority of people do not make such choices. It is easier to be "normal." Most people are desperate to be "normal," because in their mind that is an easy life. They avoid living a principled life or making difficult choices.

Most people live a life of perpetual inauthenticity, and as such, they die as a stranger to themselves. I believe I wrote this in "Snagglepuss": "The greatest tragedy there is, is to die a stranger unto yourself."

Has anything been lost with how comic books and graphic novels are often considered "art," as something "serious" to be put on college syllabi and discussed at academic conferences — as "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" most certainly will be?

I don't know if anything's been lost. I feel that comics are just another medium, and any medium is as profound or as weak as the creator, the writer and others make it. There will always be people doing incredibly insightful work in pretty much any artistic medium you can think of, including comics. Yet there are people who act perpetually surprised when something comes along in the comics medium and does something that is amazing — what could be described in certain language as being "artistically valid." I've never understood why people make an exception for comic books when we acknowledge greatness in pretty much every other form of art there is.

How should readers feel when they finish "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" or your other work?

I want people to feel a sense of wonder about the world around them, and I want them to feel like there is hope. And I know that I write a lot of dark stories. I write a lot of jeremiads against the flaws of civilization, but I don't want to leave the readers there. I want readers to feel at the end of "The Snagglepuss Chronicles" and my other work that there is hope for humanity and that there's hope for us all if we are willing to be brave enough to step off the trail that's been set out for us and create our own path, to act authentically.

Shares