One of the functions of poetry is to give form to experiences that, in the moment of poetic creation, cannot be grasped philosophically or through concepts. Take the mid-nineteenth century poet Charles Baudelaire, who first registered the shock and disorientation of the modern city, long before philosophers and social scientists had begun to think about the urban experience. Or Ezra Pound, whose epic poem “The Cantos” enacted the pre-World War II crisis of spirit that would later form the topic of countless dissertations.

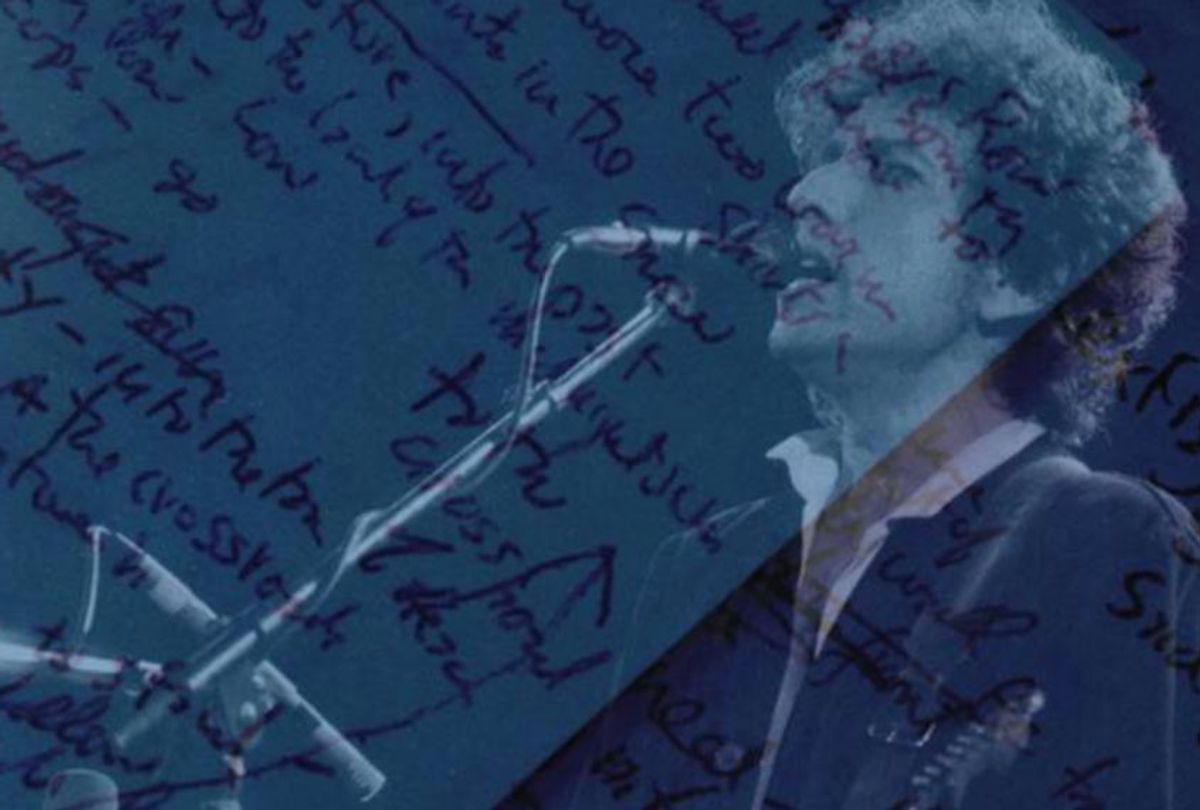

As our own moment struggles to come to terms with the undermining of objective facts and the delegitimization of expertise, and the rage of the now much-noticed “white working-class voter,” we might do well to return to Bob Dylan’s 2006 album, “Modern Times.”

Borrowing its name from Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 film, which examines the indignities of labor in the new world of industrial capitalism, Dylan updates the title by presenting a suite of songs about the experience of the modern worker in a post-industrial, globalized economy. He sings of a world in which the traditional virtues of hard work, craftsmanship, and devotion to community have been rendered economically irrelevant. Dylan’s characters belong to a group that Donald Trump has claimed as his own, the non-college-educated working classes. Through poetry and song, he gives us something that scholars and philosophers cannot. Dylan digs into the very fabric of alienation, showing us how it works from the inside out. He represents the interiority and emotional ecology of the citizens who became stereotypical Trump voters. By exposing the psychic toll of dispossession, his songs suggest why art in our own moment — if it is to matter at all — needs to account for the suffering found there.

To grasp Dylan’s achievement and its continued relevance, we need to dig in. One of the most moving songs on “Modern Times” is a stately lament called “Workingman’s Blues #2.” The title targets Merle Haggard’s 1969 hit about working men stopping off in the tavern on the way home from work to celebrate their solidarity and the dignity of honest labor. “I’ve never been on welfare,” sings Haggard proudly. By contrast, Dylan depicts a bleak world in which the work ethic means nothing, since work has simply gone bad. You can work, but you can’t afford to live:

There’s an evening haze settling over town

Starlight at the edge of the creek

The buying power of the Proletariat’s gone down

Money’s getting shallow and weak

Now the place I love best is just a sweet memory

It’s a new path that we trod

They say low wages are reality

If we want to compete abroad

After this account, not much remains of Haggard’s smug claim that a strong work ethic is all you need to be successful. This workingman looks out on his mill town and sees only a version of Desolation Row.

The important thing about these lyrics is the language used by the narrator to describe his situation, for it is all overheard. “Proletariat” would be a word the protagonist has heard bandied about somewhere, say, at the union hall. The same holds for the second-hand thought offered a moment later, “They say low wages are reality.” Who is “they?” It’s a rumor; no one actually knows why the work has gone bad.

What consoles the narrator of “Workingman’s Blues #2” is his beloved: “Come sit down on my knee,” he sings a moment later. “You are dearer to me than myself/as you yourself can see.” We shouldn’t be surprised, given the song’s interest in reported speech and what “they say,” to find that this phrase is a citation. It comes from the “Tristia,” or “Book of Sorrows” by the exiled Roman poet Ovid, sent by Caesar Augustus to the Black Sea in the first century C.E. Ovid’s poem, the last in his book, praises his wife for her devotion to him through hard times and vows that his own fame will leave her with a good name, in spite of everything. It is appropriate that it should be the “Tristia” that Dylan cites, since Ovid’s book stresses his suffering in exile; he wants to get back to Rome. The entire point of Dylan’s song, however, is that, in the world of globalized capital, everyone is an exile. Even if you are at home, you are not at home. Home is just a memory, even when you are in it. The Ovid reference both locates the workingman in a long history of exiles and singles him out as special. Not even Ovid had it this bad.

Dylan’s lyrics move swiftly between fantasy and brutal reality. The slippage from image to image enacts — performs — the impossible situation of the protagonist:

I’m listening to the steel rails hum

Got both eyes tight shut

Sittin’ here trying to keep the hunger from

Creepin’ its way into my gut

In the dark I hear the night birds call

I can feel the lover’s breath

I sleep in the kitchen with my feet in the hall

Sleep is like a temporary death

The “hum” of the steel rails evokes the now defunct world of the railroad and the possibility of escape from a small town — something like the “mail train” that Dylan pretended to hop in his great 1965 song, “It Takes a lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” But no sooner is it evoked than the fantasy is destroyed by hunger. A second later, the imaginative leap that remembers love and erotic passion gives way to the jokey phrase, “I sleep in the kitchen with my feet in the hall.” This is from an old Robert Johnson “hokum” song called “They’re Red Hot” (“I got a woman, she’s long and tall, she sleeps in the kitchen with her feet in the hall”). Here it destroys erotic fantasy. Sleeping in the kitchen is OK when it is the measure of how tall your good woman is. When you have to do it yourself, it is a humiliation. And the bleakness of the situation is sealed with the concluding line to the verse: “sleep is like a temporary death.” It’s another “overheard” phrase, to be sure, but here it brings heartbreaking sadness.

The complexity of the situation is reflected in the modulations between different types of information that are presented as each verse unfolds, often with disarming quickness:

I’m a-tryin’ to feed my soul with thought

Gonna sleep off the rest of the day

Sometimes no one wants what you got

Sometimes you can’t give it away

These four lines bring out three moments in the consciousness of the narrator and convey three completely different, though related, bits of information. The resolution to “feed” the soul with thought is the speaker’s self-consolation. For the worker who has been laid off the first thing on the agenda is to “do some thinking,” or to “get my priorities straightened out.” However, this immediately gives way to a description of what the unemployed really do, which is to sleep a lot. But then comes the bitter expression of what thought and sleep have brought up: that what you have to offer is no longer needed in this economy.

By setting the songs on “Modern Times” in desolate mill towns and rural landscapes Dylan explores a feature of small-town life that overlaps with the larger culture in the age of Trump, Fox News, and Breitbart. This is the predominance of rumor, of fragmentary knowledge, of bits of information that no one can master. The small-town world of gossip and whisper, in which reliable information cedes to hint and conspiracy, is now generalized, as lives are destroyed by seemingly impersonal “market trends” or “innovation” happening out of sight, somewhere just over the horizon. All we know about our imperiled lifestyle is what “they say” or, what “I heard.” Dylan registers the impact of this chaos on the individual. Through the movement of his very language Dylan enacts the confusion of the worker who is dispossessed and cannot quite grasp why. Moments of dream or comfort disintegrate, a second later, into humiliating self-descriptions. The crisis of the post-industrial worker takes form, not only in the thematic descriptions of despair, but in the very movement of images, as the most intimate experiences are destroyed by the brutal facts of dispossession.

Dylan’s songs capture the struggle to mobilize the remaining traces of stability and intimacy — the memory of “the place I love best,” the fantasy of a lover’s touch — to shore up the self in an economy that thrives on psychic disorientation. The crisis of our moment leaves its mark on the self in the form of a slippage between dimly remembered tradition and community, on the one hand, and acknowledgment of humiliation, on the other.

Perhaps it is not by coincidence that Chaplin’s film “Modern Times” is the first moment when Chaplin’s own voice was ever heard on film, speaking out, we might say, from the mute world of silent cinema. At last, the worker speaks. And in “Ain’t Talkin’,” the final song on Dylan’s “Modern Times,” the message that the worker offers is not a happy one. “Ain’t talkin’, just walkin’,” says the narrator, “Heart burnin’, still yearnin’.” But the “yearnin” is not for love. It is for justice and vengeance. “If I catch my opponents ever sleeping/I’ll just slaughter ’em where they lie,” runs one of the verses. Here is the voice of the workingman who at last has had enough. Here is the barely contained rage of the rural laborer, who has had his fill of fancy talk and excuses from “the ladies in Washington,” as Dylan calls them elsewhere on the album. The link between the confusion of the workingman and this concentrated violence, as the Trump era has taught us, is not coincidental.

Bob Dylan came to prominence in the early 1960s, on the basis of a series of “protest” songs written to expose injustice, racism, and war. In the more recent work of “Modern Times,” he reinvents his moral voice. The crisis of America is seen, not as a problem of false consciousness (“The Times They Are a-Changin’”) or misplaced priorities (“Blowin’ in the Wind”), but as a breakdown of knowledge, of language, of the self, which cannot grasp or understand its own alienation. Dylan’s songs on the album feel like fieldwork, a deep dive into the very language of the dispossessed, an imaginative excavation of the ruins of the self in confusion, lost in a ruined landscape, devastated by greed and polluted by rumor. These songs stand a good way from the revolutionary fervor of the songs that made Dylan famous. In these more recent songs Dylan chronicles the struggle of life, of “modern times,” as the everyday grappling, not only for dignity and a living wage, but for a language that would give voice to suffering. In the age of fake news his heroes speak through the remnants of the language of the Other, through clichés and rumors, conspiracy theories and dimly remembered phrases. He offers a less romantic account of political struggle than the vision generated in his great work in the 1960s. But it is the struggle of this moment, our moment, absolutely modern.

Shares