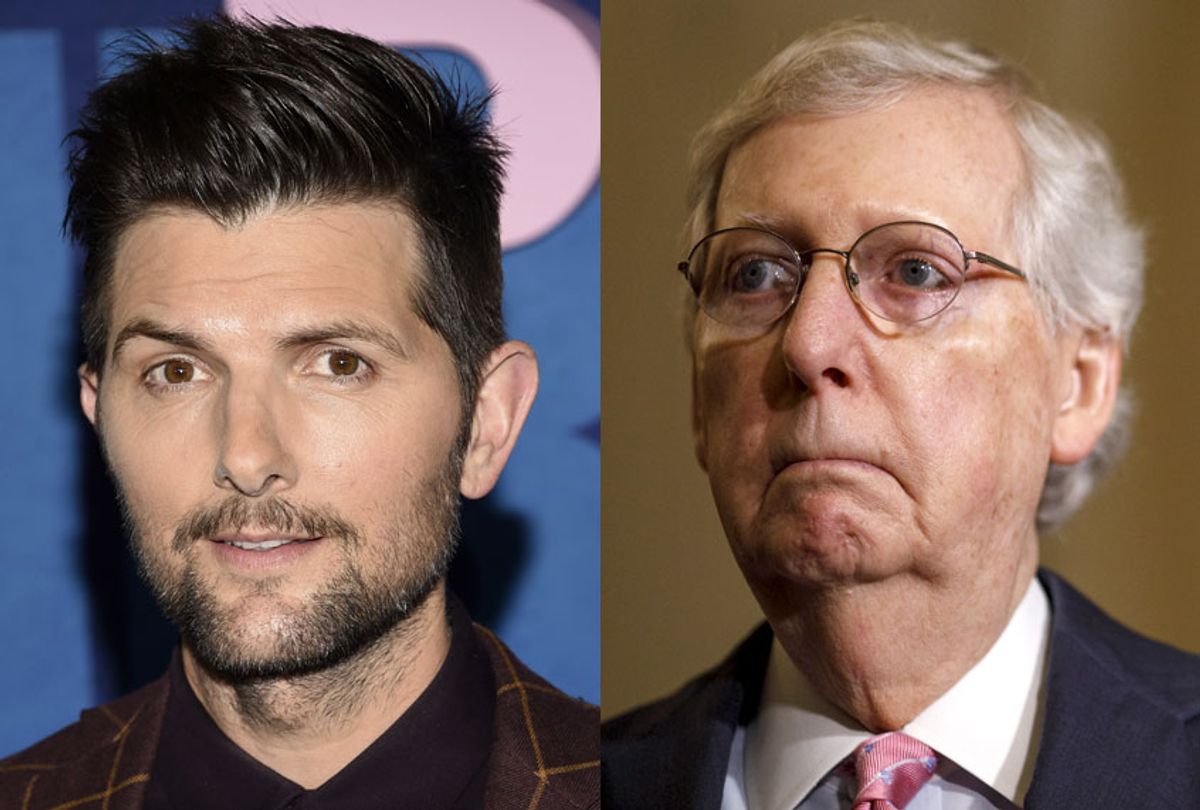

On Wednesday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s social media team responded to a tweet using a GIF of Ben Wyatt, actor Adam Scott’s character from the television series “Parks and Recreation.”

It’s one of the GIFs that’s readily available on the platform — you can find it by searching “Ben Wyatt winking” — and McConnell’s team used the image as commentary, seemingly in celebration of the news that President Donald Trump said he would fill a Supreme Court vacancy, if one arose, before the 2020 elections (despite Republicans, under McConnell's leadership, blocking Merrick Garland when the same situation arose a few years ago).

But Scott promptly issued a virtual cease-and-desist, if such a thing exists for unauthorized GIFing.

“Dear Mitch McConnell & all those representing him, please refrain from using my image in support of anything but your own stunning [and] humiliating defeat. Thanks! Adam," he tweeted.

In the past, we’ve seen musicians bristle at candidates using their songs during election season. When then-Rep. Michele Bachmann played “American Girl” at her presidential campaign events in 2011, Tom Petty reportedly sent a cease and desist; former President George W. Bush received a similar note from Petty for using “I Won’t Back Down” during the 2000 campaign.

The list of musicians who pushed back against Trump using their music during his 2016 campaign, from Steven Tyler to Rihanna, is enormous.

And recently, representatives for Dolly Parton expressed some discomfort when Sen. Elizabeth Warren made the song “Nine to Five” a signature sound of her presidential campaign without permission.

With music, there's some legal framework for artists who want to deny politicians the ability to put a song to work in service of their own image, thanks to a formalized licensing structure. But what about GIFs? Arguably, a well-placed GIF can communicate an idea just as well as a song chorus, especially as we more frequently become introduced to candidates and their ideas through their online presence. But though they are free and ubiquitous on social media, there don't seem to be agreed-upon norms yet about how they should be used in official communications and by whom.

Obviously, McConnell’s team wouldn’t be able to use Scott’s likeness in official campaign or promotional materials without his consent. But what are tweets? Is it an overreach to police an animation that's readily available to everyone who uses social media, or is this the next frontier of licensing and permissions?

It’s not the first time the “Parks and Rec” team has responded with criticism to an image of one of their characters being used in a political context with which they disagreed.

In February 2018, the NRA tweeted a GIF of Amy Poehler’s character Leslie Knope giving a thumbs-up in response to their spokesperson Dana Loesch debating gun control following the Marjory Stoneman Douglas school shooting.

“Parks and Rec” creator Michael Schur demanded the NRA remove the GIF.

“Hi, please take this down,” Schur tweeted. “I would prefer you not use a GIF from a show I worked on to promote your pro-slaughter agenda."

He continued: “Also, Amy isn't on twitter, but she texted me a message: ‘Can you tweet the NRA for me and tell them I said f**k off?’”

Nick Offerman, who played Ron Swanson on the series, chimed in: “Our good-hearted show and especially our Leslie Knope represent the opposite of your pro-slaughter agenda - take it down and also please eat s**t.”

To some, it may seem like an oversized reaction — does the average Twitter scroller really believe fictional Leslie Knope supports the NRA? But in this polarized political climate, the desire to vigilantly monitor who uses your likeness does make sense. A benign fictional character can easily become associated with wildly unrelated political messaging without its creator's consent — just look at Pepe the Frog.

Created by illustrator Matt Furie, the cartoon frog was adopted by the alt-right as an unofficial mascot of sorts during the 2016 election and became so closely associated with trollish right wing politics that, as Salon’s Matt Rozsa reported, Furie has had to fight to reclaim the image. Earlier this month, Alex Jones' conspiracy theory-promoting website Infowars settled a lawsuit filed by Furie after it sold a poster of Pepe the Frog standing with Trump and Jones.

Furie also crowdfunded $20,000 to create a new zine that features Pepe in a reclaimed light.

“According to his Kickstarter page, Furie wants to take Pepe back to the days when he was a 'blissfully stoned frog' who 'enjoyed a simple life of snacks, soda and pulling his pants all the way down to go pee,’” Rozsa wrote.

He continued: “[Furie] also wants to decouple the character's image from the meme who ‘stuck around the internet long enough to become an institutionally recognized hate mascot,’ an experience that Furie describes as ‘a nightmare.’”

Reasonable people are not likely to conflate a politician's use of a GIF with a celebrity endorsement. But celebrity is nothing if not an exercise in crafting an image, which becomes even more layered when the meme in question is a celebrity performing an iconic role. In this case, it’s not just Adam Scott's image in play, it's the beloved Ben Wyatt's too. With campaign season ramping up, it will be interesting to see how celebrities maintain their images when presidential hopefuls use literal looping animations of their faces to try to score political points.

Shares