It’s strange how two memories in your life, separated by decades, can touch, as if the years have curled into one another, forever locked in a fatal embrace, tethered together by a defining moment. I can’t see one now without the other. I’m a beaten-down middle-aged man driving a minivan by the village green on my way to the Walmart in a cold, New England town. I’m young and full of promise, driving a white pickup truck up a steep Rocky Mountain road as the summer sun rises.

Just before I met my wife Katherine, when I was nineteen years old, I lived with my aunt Sheila for the summer and worked as a tour guide at the Lost Gold Mine.

As we turned onto Main Street at the entrance of Black Hawk, the town still quiet in the hollow of the cool morning, I looked at Mike and asked, “What do you mean you don’t like the way men look at me?” knowing full well what he meant.

“Like you were a piece of meat, all of Allen and Stan’s friends,” he replied, emphasizing the word friends that gave it an illicit weight.

“Oh, well, I think they’re looking at you,” I said, trying to shift the attention.

We were both working as tour guides at the Lost Gold Mine, a tourist trap set at the top of Eureka Street up high in Central City. The mine was owned by an unlikely gay couple, Allen and Stan, who were friends with my aunt Sheila. They agreed to hire us sight unseen based on Sheila’s recommendation. “Bill’s adorable,” she told them, and within a month, Mike and I had driven cross-country, during summer break from our college in North Carolina to live with Sheila.

For five bucks a head, we would lead a group through a hundred-yard tunnel tucked away behind a metal door in the back of a gift shop. It was brimming with authentic Western memorabilia imported directly from China. The conclusion of the tour was a plea, “Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. I’d like to point out the tip bucket on your way out. I’m working my way through college, and that’s my little gold mine!”

My ingratiating request usually guaranteed a modest tip, but Mike’s halting, deadpan delivery would often net him a disgruntled reply, “Consider it lost.”

Mike and I shared a room in my aunt’s two-bedroom 1950s ranch in a tidy Denver suburb. I suppose the best way to describe Mike was beefy, with a head slightly too small for his body. Most of the time, we worked the same shifts, but occasionally he would wake up early, grumbling to himself, and slam the door shut, unhappy to be making the trip alone. On one of those days, Sheila skipped work and announced that the two of us would take a sightseeing day trip to Colorado Springs. She worked as a bartender at a golf course clubhouse, but she had bigger dreams and a bank account full of money to back it up from a sexual harassment lawsuit settlement. “My boss walked into the supply room with his pants down and told me to suck it. Look who’s sucking it now,” she said. She winked and exhaled a cigarette smoke ring.

Sheila was a tall woman with permed curly brown hair and big, round brown eyes framed with fake eyelashes. She had a sexy low voice and smoked long, skinny Virginia Slims cigarettes, held at the tips of her first and second fingers, like the 1940s film star Bette Davis. Blue jeans and T-shirts were the extent of her fashion choices. She could make anyone feel at ease, but could not do the same for herself.

I loved her intensely.

Before I left for Colorado that summer, my mother warned me about her sister. With all of our dead ancestors peering down from their oil portraits, my mother in her starched nursing whites sat erect in one of the wingback chairs and regarded me as if consulting a terminally ill patient. She gravely announced, “I want you to know that Sheila is”—she hesitated, then lowered her voice—“a lesbian.” Her face winced as if she had bitten into a lemon. I imagined the police breaking down our door and arresting my mother on the spot for uttering that word, her sensible orthopedic shoes dragging and her hair a frightful mess as she was carried away sobbing and screaming, “I won’t say that word again, I promise!”

A half smile crept onto my face.

“Don’t let her change you,” she commanded, and then asked, “Are you listening to me?”

“I’m sorry, Sheila is a what?”

I could not resist.

As we rode south in her white Mustang toward Colorado Springs, Sheila took a quick drag from her cigarette, hesitated, held it up and away from her face, and then glanced at me. “Have you ever had an experience with a boy?” She then blew smoke through her pursed lips to the side like a curling question mark.

“Sort of,” I said, hesitating.

“And was it delightful?”

“It was confusing,” I replied.

“You are who you are,” she said. “I’m going to buy a bar. One of those bars, although you can’t drink when you own one.”

I knew what kind of bar she was talking about but had never entered one. In the 1980s, they were nondescript buildings with blacked-out windows on the edge of town and were given fancy names like the Exit, which is exactly where we ended up that evening. Sheila parked the car in the bar parking lot, turned to me, and said, “I’m going to introduce you as my son, because calling you my nephew implies something else.” She looked me in the eyes, took my hand, and said, “Don’t be nervous, honey.”

But I was. Here in the middle of nowhere, I worried that someone might see me and label me.

When we walked into the bar, the contrast between light and dark was startling. As my pupils dilated, I felt the stare of hungry eyes zero in on me like lions focusing on a gazelle timidly approaching the watering hole. We sat down at the bar. The bartender wandered over, smiled at me, cocked his head, and asked how old I was.

“How old do I look?” I innocently asked.

“Old enough to go home with me tonight,” he replied.

I made a mental note to say twenty-one the next time anybody asked.

He pushed two drinks toward us and said, “From your admirer,” while glancing toward the end of the bar.

“Don!” Sheila shouted, throwing her hands over her head and jumping up from her barstool.

I watched Sheila run laughing toward the man she knew named Don. He looked to be in his early twenties. Sheila motioned for me. As I walked toward them, I could see that he had blue eyes. If there was a faster way to get the alcohol into my bloodstream, I could not find it and tipped the rim of the glass into my mouth, feeling the shock of the ice hit my teeth and a slight dribble run down my chin.

“Don, this is my son, Bill. What do you think of him?” Sheila asked, holding her hands out like a model presenting valuable merchandise on a TV game show.

“Cute,” Don replied, and offered his hand. I quickly wiped the drink off my chin with my hand, brushed it against my shirt, and then shook his hand.

“The hell he’s cute, he’s gorgeous.” Sheila winked at me as she put her arm around my shoulder.

Don turned to me and asked directly, “Why do gay men have lesbian friends?”

“I don’t know,” I replied, glancing at Sheila who was rolling her eyes.

“Someone has to mow the yard,” he replied, slapping my shoulder.

I laughed, without really knowing why. Don would continue to tell me jokes in rapid-fire succession until Sheila eventually said half jokingly, “Don, enough. You’re making him dizzy!” I don’t know if it was the jokes, the attention from Don, or the vodka tonics, but I was intoxicated. Time lost its meaning. And it was like for the first time in my life I had stopped dragging the stone in me up a mountain. I froze in both the relief and danger of being seen. It was the beginning of the evening, and suddenly it was late night. The bar buzzed with activity and the deep bass beat of the music. Laughter bubbled over the hum of voices.

“You’re good-looking, for a man,” I heard a woman who had joined us shout over the din. I turned my head to look at Don.

“She’s talking to you,” he said, and then rubbed his knee against mine.

Boys don’t touch each other like this. I heard my mother’s sharp voice.

“I have to go to the restroom,” I said, and stood up, attempting to find my balance, altered by alcohol and honeyed attention. That was when I felt Don’s hand holding mine, his hand dragging time to a halt.

We opened the bar door and stepped out into the night. There was a truth in the deafening silence that washed over a person at two in the morning under the starry Colorado sky. The beat and hum still pulsing through our veins, we walked to his car, Don’s arm around my shoulder, mine around his waist, and then his lips on mine. The air molecules became charged, and I felt as if I were at the basin of Phantom Canyon as a cold wind blows in, and a June snowfall glitters on the red canyon walls, and then at the top of Royal Gorge on a suspension bridge, staring dizzily a thousand feet below at the Arkansas River cutting through time. When time started up again, our foreheads were touching, and my arms rested on his shoulders as we breathed deeply, the distant beat of the bar behind us and the moonlit sky stretched over the silent Rockies. And then I heard the hum become Sheila’s words, like the recognition of an alarm in a dream. She was walking quickly toward us. “He’s not sure yet if he’s gay, Don!”

But there was no more confusion. I knew. All it took to confirm was a single kiss.

On the last night before I returned home to North Carolina, I woke up late at night, the remnants of a lurid dream lingering in the air, the pickup truck climbing a red mountain road so steep that it tipped back upon itself before tumbling into the dark abyss. As the dream vaporized, I walked into the kitchen, my heart still racing in my chest. Sheila was sitting at the kitchen table in the dark, an open bottle of vodka in front of her as she clutched a cigarette that mysteriously clung to an entire length of ash. Her gaze was fixed somewhere in the middle distance. Not wanting to startle her, I turned around and headed back to my bedroom. “Uncle Dan was like us,” she said without looking at me.

“What?” I asked.

“My uncle Dan moved to California where he could be himself. I told your grandmother that I was like Uncle Dan,” she said.

I walked into the kitchen and sat down across from her, the moonlight filtered through the blinds painting her face with horizontal shadows.

“‘Sheila Marie, when are you going to find a good man and settle down?’” she said without blinking, mimicking my grandmother’s voice. She returned from her memories, and her face gathered recognition of the present. She placed the burned-out cigarette in the ashtray, cupped my face with her hands, and said, “In a previous life, I was pregnant with you, but the ocean swept us away.” She believed in reincarnation and that the people who surrounded us now were the same ones who surrounded us in our past lives, but in each go-around, we assumed different roles. On some ancient shore, Sheila lost me before she could give birth, and in this one, she was terrified of losing me again. Looking back, I can see that Sheila was struggling, and so was I. We needed to cling to each other, so that if the world erased us, we might get another chance. She saw me for what I was, something unfinished.

She pushed herself up from the table, walked to the window, lifted a single slat to peer through it, and said, “God, I hate going to bed at night. I always feel so alone.” She pulled out another cigarette from the pack, lit it, inhaled a quick sip of smoke, and then released it while saying, “Now you’re leaving me too.”

In the morning, I got dressed in the clothes Sheila had bought for me, packed my bags, and tiptoed into her room. She was still sleeping, or she was passed out. When I nudged her, she mumbled some unintelligible words but did not budge. I tapped her on the shoulder repeatedly, each time pushing her more firmly. Finally, I said, “If I don’t go now, I’ll miss my flight.” She sat up with a start, like a corpse popping up after rigor mortis sets in.

When I walked off the plane in North Carolina, my mother cocked her head. She hugged me and then placed her hands on my shoulders, holding me at arm’s length. “You look different, more filled out,” she said. She looked down at my shoes and then slowly moved her gaze up, like she was analyzing an outfit on a mannequin, her lips pursed and their corners turned down.

“New clothes,” she said.

But it was what she did not say, her Southern way of saying something in place of saying what she thought, Those are homosexual clothes.

I slept in my childhood bed that night, my feet hanging over the edge, and stared up at the ceiling, thinking about the stars in Colorado. I touched my body the way Don had.

In the morning, my mother was sitting alone at the kitchen table, her back to me, and I looked at the nape of her neck. One of my earliest memories was sitting in the back seat of the station wagon, my father driving and my mother sitting next to him. She smoothed the hair of her new pixie cut with a white-gloved hand as we crossed the bridge over Buffalo Creek. Our new house on Latham Road appeared above the dashboard, and I kept watching her fuss with the hair on the back of her neck, wondering what the expression on her face might reveal.

“Mom, Sheila and all of her friends are just like me. The love they have for each other is the same,” I said. She didn’t turn around, just reached up and patted her hair. I sat down at the table and glanced at her face. It was the same grimace I saw when she uttered the words lesbian and homosexual.

“I knew it the minute you walked off that plane,” she said. “Sheila dressed you up in those clothes.” She looked down her nose at my shirt, and then she continued in a high-pitched, singsong mocking tone, attempting to imitate my aunt Sheila, but sounding nothing like her. “It’s OK, Bill, just go ahead and be gay!”

She had never accused me of being gay, preferring other scare tactics like effeminate.

Don’t put your hands on your hips like that. It looks effeminate.

Those flip-flops make you look effeminate.

I didn’t say I was gay. I couldn’t be that strong. I was testing the waters, and now I was drowning, and she knew it.

“Do you want to be a woman too?” she asked.

I winced and began to retreat. “Mom, I’m not gay. I think, maybe, I’m confused.”

She cast aside her Southern euphemisms and went straight for the jugular. “It’s disgusting is what it is. There is nothing natural about it. Let’s pray.”

The torture would continue for months. It was calculated and surgical, like the removal and irradiation of a gay tumor. Conversation therapy doesn’t always occur at a facility. Often, it takes place at the dining-room table.

I couldn’t be who I was without Sheila, and the ocean of space between us swept us apart. I returned to the closet, and Sheila returned to the bottle. Neither of us was strong enough to maintain the path we cut together along Clear Creek.

Sheila died in the middle of the night from a sudden brain aneurysm when I was in my thirties. She was living in a trailer park in Florida alone, except for the two dozen or so exotic birds that she was breeding as her next big moneymaking scheme.

I did not cry when she died, less because she would not have wanted it, and more because I felt like I did not deserve to. It was another thing that Sheila and I had in common, how our secret kept us far away from loving ourselves.

Twenty-five years later, my wife, Katherine sits next to me, in the passenger seat of our minivan, and fidgets with her hair. The families who settled this small New England town built stone walls at the edge of their existence. Hundreds of years later, the boulders crisscross fields and tumble into the woods, staking long-forgotten boundaries. I drive our minivan in silence past the pumpkin-colored village colonial, past Oak Hill cemetery bordered by a crumbling fieldstone wall, and pull into the Walmart parking lot. “Just park the car now, Bill. I have to ask you this, or I’m afraid I never will.” When I turn off the ignition, Katherine’s question pierces the heavy silence.

“Are you gay?”

The air in the van is too heavy. Through the vehicle’s window, I see a family of four open its car doors. They take each other’s hands, shuffling across the pavement. They disappear into the dark and then reappear beneath a yellow circle illuminated by a parking lot light. Their questions, I imagine, are easier to ask and to answer. Do we need more paper towels? How much milk is left? Will we make it back in time to watch American Idol?

She waits. Doesn’t she already know the answer?

It has always been there, but I kept it cordoned off for all these years. I built my life on No. That life is crumbling now, and neither of us can keep pretending I can support it.

“I don’t want to be,” I reply. An answer that is truthful, but one I hope won’t bring all of the walls down.

For a moment, the world stops turning, and we stop breathing. Our whole lives suspended in the silence that a shattered secret can make. I exhale as she inhales.

“Oh God,” she says, and looks through the car window. Her body slumps under the weight of the words, filling the van like water.

“Oh God, oh God, oh God, I told myself to be ready for the answer,” she says. “But how could I prepare for this?”

But I know, the hardest things to prepare for are sometimes the things that we already know. Despite the rubble I’ve made, a lightness tugs at me, pulling me up as Katherine sinks below the surface.

For the first time, I see that nineteen-year-old traveling that one crooked road along Clear Creek.

And he sees me.

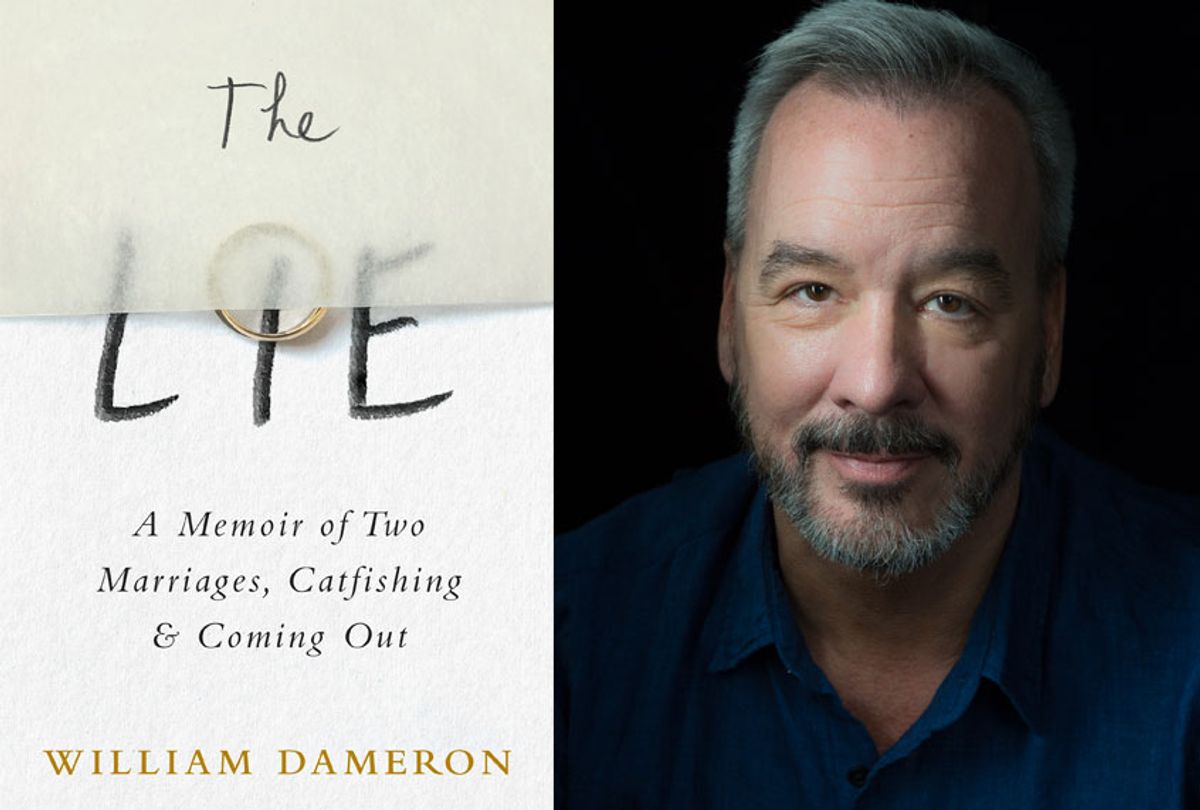

Shares