Early on Sunday evening, two hours after polls closed, people in Istanbul rubbed their eyes as the pro-government candidate, former prime minister Binali Yildirim, conceded the race for mayor of the city.

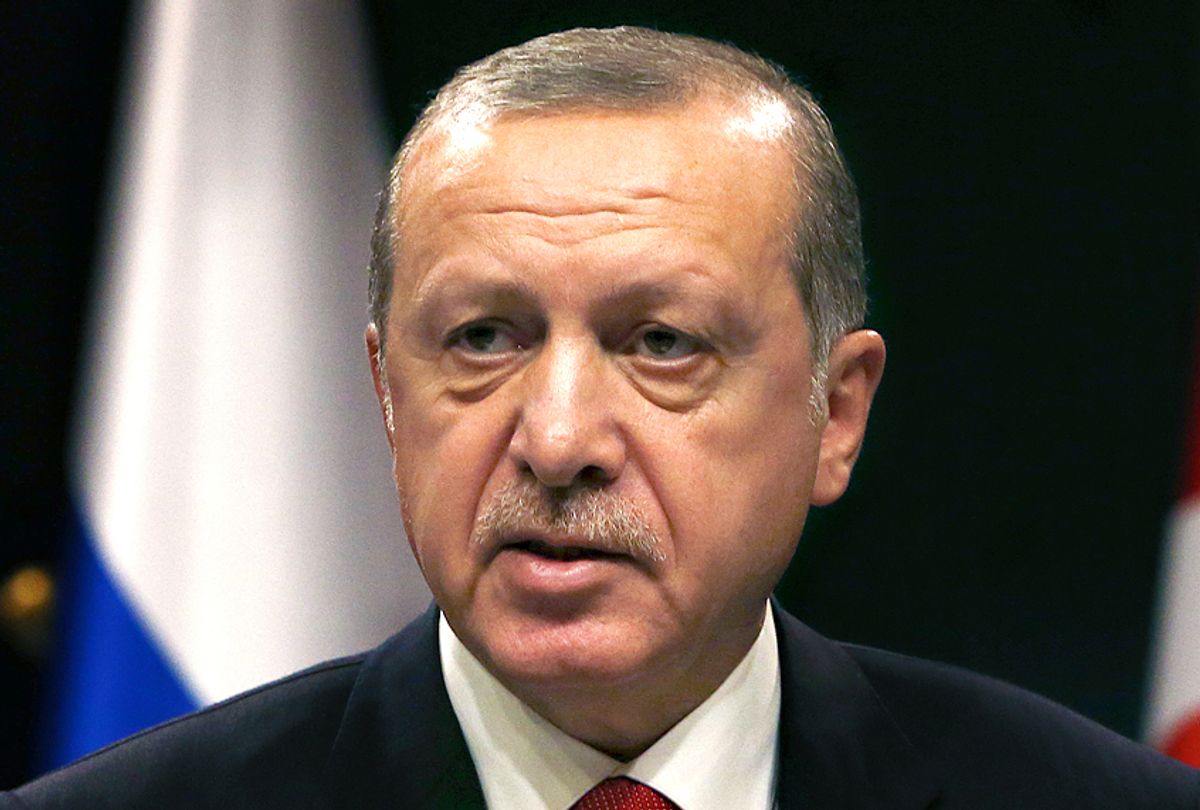

Jubilation quickly spread on the streets and onto social media, though observers fear further chaos. Many hailed the end of the era — or the beginning of the end — of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the authoritarian president who has all but broken up the NATO alliance and driven his country away from the dream of EU membership.

This was a huge defeat for Erdogan, a deeply divisive figure both at home and abroad, who faces dissent inside his own party and a deepening economic crisis. He had insisted that the Supreme Electoral Council cancel a March 31 vote — which opposition candidate Ekrem Imamoglu had won by only a few thousand votes — over a minor technical issue. According to the latest figures released on Monday, Imamoglu won the rerun with 54.2 percent, scoring higher than any candidate in the past 35 years. Erdogan, a former mayor of Istanbul himself, received 25.2 percent in 1994.

Istanbul is Turkey’s largest city, home to about a quarter of the population and a third of the economy. An old dictum of Turkish politics proclaims: Who rules Istanbul, rules Turkey. Erdogan, whose local patronage networks are believed to be heavily dependent on income from municipal projects, is painfully aware of it.

“Who loses Istanbul, loses Turkey,” he repeated during the campaign.

In another symbolic reversal for the president, Imamoglu, 49, gained popularity in Istanbul for his participation in the 2013 Gezi Park protests, which Erdogan doused in tear gas and rubber bullets, brandishing his electoral credentials and labeling his critics looters and foreign agents.

It was the episode that for many marked the beginning of Turkey’s descent into authoritarianism. Imamoglu successfully ran for mayor of the Beylikduzu district of Istanbul after the protests, launching a career that one day could even land him the presidency.

“[Imamoglu] is a man that emerged out of Gezi Park protests in 2013 and Gezi has won today,” Gurkan Ozturan, the executive manager of Dokuz8, Turkey’s only remaining independent news agency that operates nationwide, told WhoWhatWhy.

“But will he run for presidency already in 2023? I hope not… He is a good mayor and I think we have quite many years ahead for him as long as he does not diverge from his humanist, democratic position.”

Erdogan is not known to take such blows lightly, which could add greater instability to Turkey. Tens of thousands of his political opponents have been jailed — from army officers, judges, and university professors accused of treason down to high school children charged with insulting the president on social media. Mainstream media have been taken over, sometimes in violent police raids.

In recent years, the country has consistently outranked Iran and China as the world’s leading jailer of journalists.

People chanted “Her sey cok guzel olacak!” — meaning “Everything will be just fine!” — late into the night in Besiktas and other opposition strongholds in Istanbul. Their victory builds on earlier momentum that helped the opposition win the mayorships in the capital Ankara, the third-largest city Izmir, and other major metropolitan centers on March 31.

But an eerie sense of tension and disbelief continued to haunt most observers, not because the government lost, but because it seemed strange for Erdogan to concede a loss after doing everything he could to snatch victory from defeat.

“Anyone who says they know what will happen next is deluded or perhaps blinded by joy,” Jenny White, a prominent Turkey analyst at Stockholm University, told WhoWhatWhy.

In the past, the government has arrested mayors it deemed inconvenient on various charges, or made it hard for them to govern, she added. Imamoglu already faces a fraud investigation.

No blatant violations have been reported so far in Sunday’s poll. But, according to White, “The government side tried some dirty tricks — canceling ferries and flights from vacation areas on some pretext, with the next available scheduled trip being after the elections.” Observers also flagged a desperate move by the government a few days before the election to elicit a letter from a jailed Kurdish leader in an effort to split the opposition vote.

“Turks are very proud of the fact that their elections mean something,” White noted. “By canceling the last one for no good reason other than that he didn’t like the result, Erdogan insulted the public will and put in motion the toppling of his own legitimacy.”

Erdogan faces a possible rebellion from disgruntled former allies in his own party, added Dimitar Bechev, a prominent expert on European policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in a tweet.

Ahmet Davutoglu, a former prime minister, and Abdullah Gul, the country’s former president, who also were sidelined by Erdogan, are believed to be preparing to challenge him by re-entering politics.

But Turkish society is incredibly polarized after years of turmoil including repeated elections, protests, military operations, and even a failed coup attempt in 2016 that many blamed on the US. And Erdogan, who gave himself nearly unlimited powers in acontroversial referendum in 2017 and cemented that victory in a similarly controversial presidential election last year, isn’t going anywhere immediately. The next general election isn’t scheduled until 2023.

Amid the continuing celebrations, many worry that the government may stir violence and chaos in the short term in order to reclaim its grip on Istanbul.

“Present at the back of everyone’s mind is the question, what will Erdogan do,” said White.

One ominous straw in the wind — a statement after the results came in by Nationalist Movement Party leader Devlet Bahceli, a key government ally on the far right: “Probably and possibly, the results of the twisted political language based on unfair and unjust victimization in İstanbul will be visible in the upcoming days.”

Shares