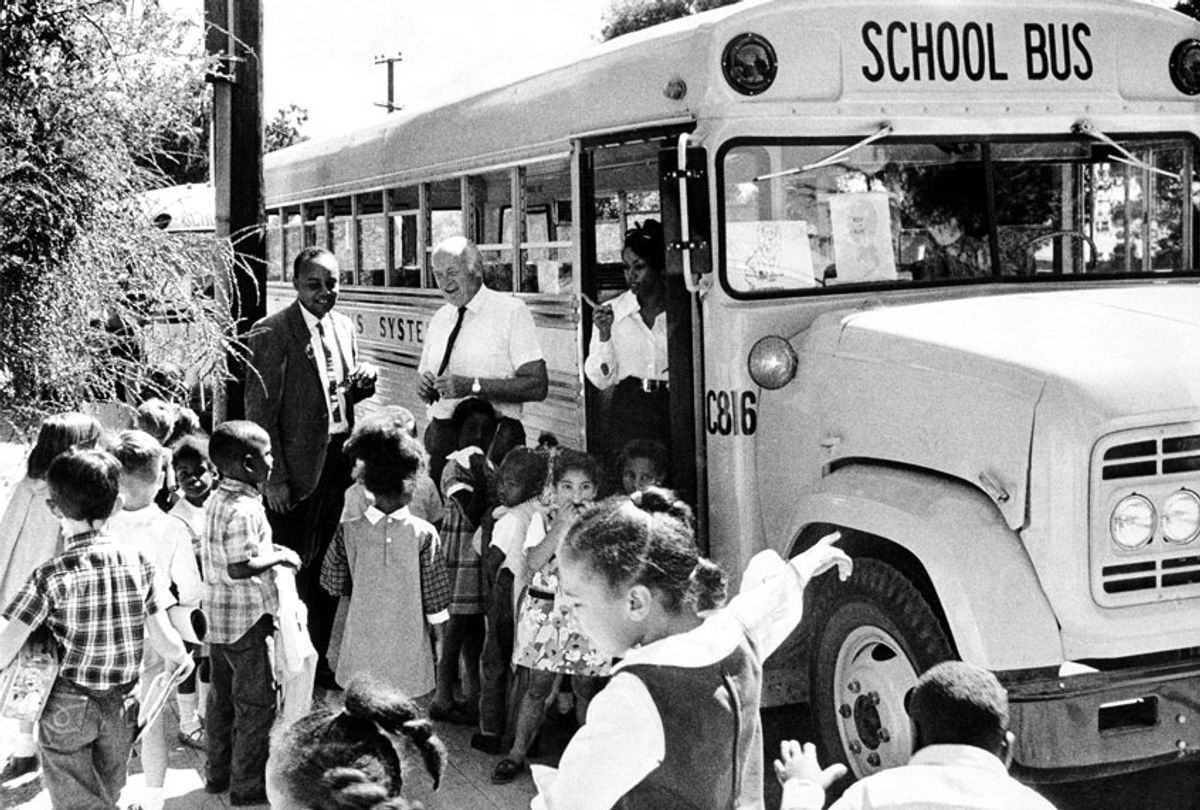

For about 24 hours at the beginning of second grade, a boy named Steve was a major mystery in my life. His name was right next to me on the first day of school, on a label affixed to the other side of a shared two-person desk unit. But Steve himself was not there. I had no idea why at the time, and in fairness I still don’t. Maybe he was sick. But quite likely it had something to do with the fact that it was the first day of the first year of a historic experiment in school desegregation, and Steve was riding the bus from the other side of town.

I spent much of that first day wondering what Steve would be like. Was he into baseball cards and comic books? Where did he fall on the relative merits of the Three Stooges and the Little Rascals? (Yes, those were antediluvian cultural references even at the time, but fed to us daily on afternoon TV.) Would we be best friends and have Huck-and-Tom adventures together?

One question I did not ask myself was whether Steve was a “Negro,” as we said at the time. Someone must have explained something about busing to me, but I had no grasp of the social dynamics involved. My parents were university-educated liberals who supported the civil rights movement and all that, but before that year I personally knew exactly two black people: One of them was the woman who cleaned my parents’ house and the other was a biracial kid who attended our school, pre-integration, and was therefore perceived as not exactly black. It took me years to appreciate that my understanding of that kid had been shaped by racism.

This was in Berkeley, California, in the fall of 1968, a few months after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. As much of the country has recently learned, Kamala Harris, the future U.S. senator who is now a presidential candidate, started school in Berkeley not long after that. (After some confusion, the Harris campaign has issued a clear chronology: She attended a private kindergarten, and entered the Berkeley school system in 1970, as a first-grader. She moved away in middle school, and spent the rest of her adolescence in suburban Montreal.)

Harris did not attend the same elementary school as Steve and I did, but we could have walked from our school to hers within 20 minutes. I played Little League baseball there. (For you Berkeleyans: Steve and I went to Oxford; Kamala went to Thousand Oaks.)

In Harris’ perhaps-slightly-scripted confrontation with Joe Biden last Thursday evening in Miami, she drew on that experience to corner the former vice president on his previous opposition to busing and his political partnerships with old-line segregationists. “You know, there was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day,” Harris told him. “And that little girl was me.”

National reporters have suddenly taken an interest in the distinctive story of Berkeley’s voluntary busing program, which is a strange experience for the modest handful of middle-aged people who actually lived through it. None of the stories published have been egregiously wrong, but few of them have captured the peculiar atmosphere of that place and time, perhaps because that’s almost impossible to do.

Both right-wingers and Biden defenders have sought to chip away at Harris’ personal history at least a little. Conspiracy-friendly conservatives have recirculated an old story claiming that Berkeley schools were desegregated long before Harris came along, which is absolutely false. As for the concocted controversy over whether Harris is authentically “black,” it's clearly inadvisable for me to get involved. But if she’s not black then Barack Obama isn’t either.

Much of that nonsense largely reflects our continuing anxiety over the intersection between class and race: As the child of university-educated academics, Harris is unmistakably middle-class in background and affect. Given her background, in fact, I initially wondered whether she might have lived on the “white” side of town and been bused to a “black” school, which would certainly have been an interesting wrinkle in her tale. But that’s not the case either.

As someone who lived through the same experience in the same place, on the other side of the color line, I can testify that Harris’ chronology is accurate and her facts check out. Whether her life story (or mine) or the anomalous social conditions of Berkeley at the end of the ‘60s have any relevance to the continuing crisis of school segregation, or to the 2020 presidential campaign, is quite another matter.

Like my friend Steve, young Kamala Harris belonged to a cohort of kids from the “flats” — a codeword for the modest West Berkeley neighborhoods adjacent to San Francisco Bay, which were then largely working-class and predominantly black — who got bused to previously all-white schools in the “hills.” That was the pattern from kindergarten through third grade, and then it reversed. From fourth through sixth grade, for instance, I was bused from my all-white neighborhood of spreading London plane trees and Arts & Crafts houses to a ramshackle school deep in the “flats,” a few blocks from the waterfront in what was then an entirely black neighborhood.

Busing in Berkeley was a blunt instrument, applied with laudable intentions, that achieved what can best be called mixed results. It was meant to address the abundant contradictions of a city that already had a reputation for radicalism and nonconformity, yet remained functionally as segregated as anyplace in America. There was a tangible “red line” running north and south through Berkeley, along what was then called Grove Street (and today is called Martin Luther King Jr. Way). Although there was no Jim Crow-style segregation in California, it was virtually impossible for black people to buy property east of that line.

There were certainly some white people who lived west of Grove Street, because they were working-class or because they were in a hippie commune or because they were making a half-baked political point or because they were the distant early warning system for gentrification. (You’d be lucky to find a house in any of those neighborhoods for less than $1 million today.) My older brother fell into at least two and possibly three of those categories at various times. But that tangent leads outside this story.

When people ask me what it was like to be bused, and what I took away from the experience, I feel a historical responsibility to answer carefully. The short answer is easy: It sucked. Columbus School, the “intermediate school” I attended in West Berkeley from fourth through sixth grade, was (to my innocent eyes) unbelievably decrepit. Nothing worked: The Venetian blinds were permanently askew, the water fountains had been disassembled, the bathrooms were frequently flooded, or simply locked. Broken windows had been patched with duct tape in a vain attempt to seal out the unique chill of a San Francisco Bay fog. The playground appeared to have been paved with low-grade road asphalt that left spectacular burns and scrapes anytime you wiped out on it. Seagulls frequently shat on us with malicious glee, although I guess the school board cannot be blamed for that.

Now, was it an important education in American inequality for me to experience that school first hand? No doubt, and the irony wasn’t entirely lost on me even then: Kids in that neighborhood had only known run-down schools where everything was broken, and must have been startled in an entirely different way by the calm, clean, orderly, tree-shaded school I had previously attended. I don’t believe I’ve ever had a conversation with a black person from Berkeley about what that was like, which is another example of the kind of racial blindness you don’t even notice.

I’m not sure there was much benefit for anyone, on the other hand, in the lawless “Lord of the Flies” atmosphere at Columbus School after a few dozen haute-bourgeois white kids were bused in and dumped there with no preparation, counseling or oversight. Admittedly, that might not have had much to do with integration per se. It was more like a total failure of adult supervision, born out of overconfident, idealistic social engineering and the now-almost-incomprehensible norms of 1970s parenting and education.

A woman named Sophie Hahn, who attended Columbus School with me and is now on the Berkeley City Council, evidently remembers it in more glowing terms. She told the Los Angeles Times she had learned “African history and some Swahili” and that we sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing” at school assemblies. I remember that too, Sophie — and I remember that after that assembly my friend Jon and I cut school the rest of the day and wandered around Berkeley on our own (at age 10), and that nobody even noticed.

My principal memories of fourth grade, besides that one, involve playing Old Maid with Black History playing cards (I’m serious) and figuring out who I had to fight to establish my place in the pecking order. So I learned about the immortal P.B.S. Pinchback — governor of Louisiana for 36 days during Reconstruction! — and I learned that in order to escape merciless daily bullying I needed to victimize someone weaker than me. So I beat up a kid named Alex, who was perfectly lovely, for no reason at all. (The principal was mystified and disappointed.) Then I fought a tougher kid named Michael, more or less to a draw, and after that things were more peaceable. Alex got into a really good college, much later on, and Michael (whose parents were hippies) became a born-again Christian. I don't think I had anything to do with any of that.

That too was an education in its own way. In fact, I hesitate to draw larger conclusions about the impact of “busing,” either on my own life or on the community around me. I had black classmates who were allies at that school, and others who were enemies. Some black teachers and administrators took a benevolent interest in me, and others punched the clock and didn’t give a crap. I went bird-watching for the first time with a retired African-American teacher who was a famous Berkeley eccentric. A black girl a year older than me decided one afternoon that she would teach me how to French kiss. (I do not remember her name.) I had never even heard of James Brown before I went to Columbus, which was certainly a pitiable lapse in my education.

There remained a cultural, social and economic gulf between us, of course, which a few years at the same school could not bridge. At the end of the day, most of the white kids got back on the bus to ride to our architect-designed houses on leafy, hill-climbing streets, while most of the black kids stayed behind, somewhere near the broken school, on blocks of modest one-story bungalows and dreary breeze-block apartment buildings. There wasn’t much dire poverty in West Berkeley by big-city standards, and a lot of it was just standard working-class America. But there were things I had certainly never seen before: Men drinking and gambling in the street during the day, or moldering Buicks abandoned for months and gradually stripped down to the chassis.

Those raw and often painful contrasts, or conflicts, ultimately drove both Berkeley and America away from busing. I can understand why political leaders like Joe Biden, along with many parents (not all of them white), turned against it. I also understand why many social scientists now contend that the difficulties were worth it and that most children benefited, black, white or otherwise. It was disruptive and I was unhappy. I learned important things about my society and myself. Pretty much none of that happened in the classroom.

School enrollment in Berkeley fell by nearly half in the 15 years after 1968, as middle-class white parents pulled their kids out of school in large numbers. More recently the school board abandoned wholesale busing in favor of a complicated, micro-targeted desegregation plan designed to keep kids relatively close to home, while ensuring that no school is more than 60 percent of a given race. That formula is seen as a potential national model, but it can do nothing to address the underlying conditions that drive segregation: Exploding housing costs and the Bay Area’s tech boom have driven most of Berkeley’s onetime African-American residents out of town.

I didn’t form any long-term friendships across the color line during the busing years, which isn’t that surprising. But I do feel a common bond with anyone, black or white, who went through that strange social crucible. To return to Steve, my second-grade seatmate at previously all-white Oxford School, up in the hills: He was absent for the first day but showed up on the second, and I realize now that I never asked myself what that was like for him.

Steve and I were friendly enough, but did not become Tom-and-Huck best friends. He liked the Three Stooges, if I recall correctly, and may have been the kid who introduced me to the Universal monster movies of the 1930s and ‘40s (another staple of mid-afternoon UHF broadcasting). He was better than me at math and music and sports. I don’t remember anything about his views on Willie Mays or Doctor Strange.

I haven’t used Steve’s last name because I haven’t been able to track him down. He was an extremely easygoing guy and probably wouldn’t mind; I’m halfway hoping he gets in touch. I ran into him once many years later, when he was working at a record store and I was a customer. (So, yeah, that was a while ago.) We had similar tastes in jazz: He recommended something and it was really good. We definitely didn’t talk about busing or Berkeley’s racial history or anything like that. We had both been there. We said we would keep in touch, but of course we didn’t.

Shares