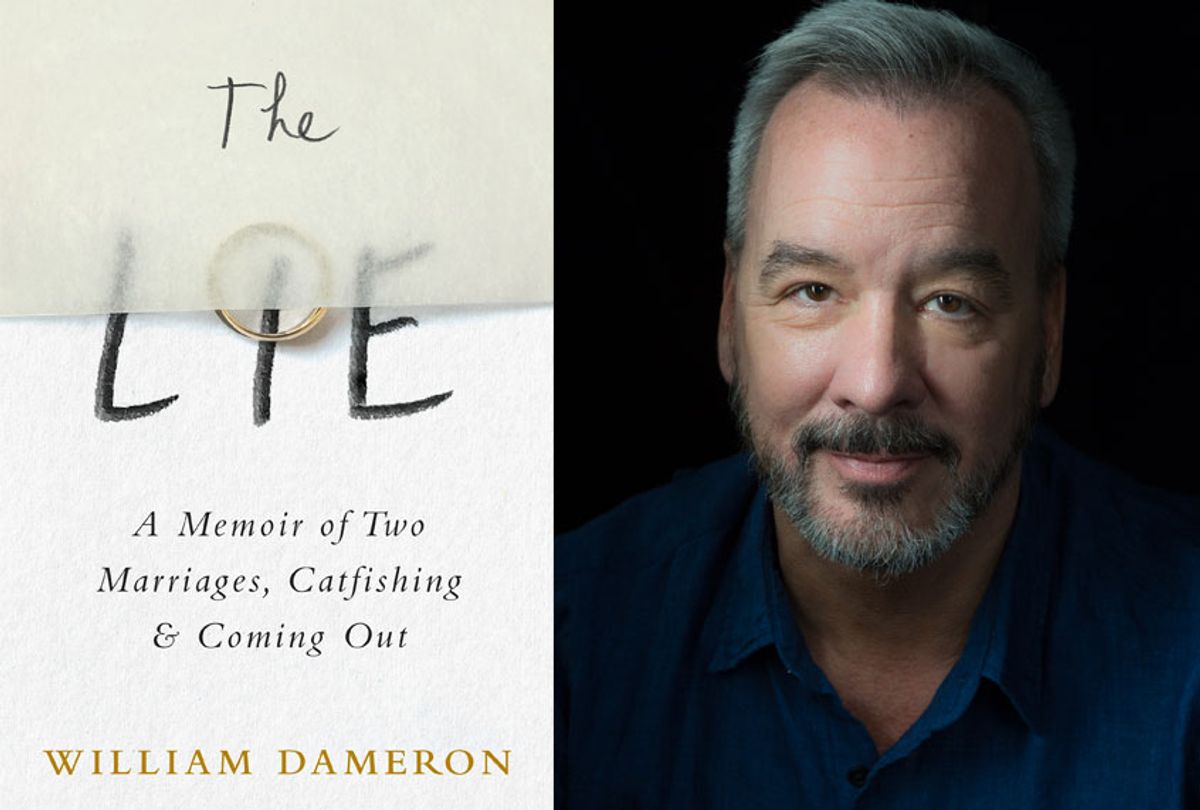

My first introduction to William Dameron came via my inbox here at Salon, pitching an essay about how he discovered that a selfie he had once posted had been used multiple times over several years in different catfishing schemes. People searching for a photo of "40-year-old man" to pose as found a photo of him, high up in the Google results, and would use it to hide behind. Victims of the deceptive dating schemes did reverse searches, found Dameron, and reached out to let him know. "Your face has meant a lot to me," one woman wrote. "And now I’ve found out it’s a lie."

That was the hook. But what really interested me about his pitch was the last part, where he confessed that in his essay, he could also offer the perspective of someone on the other side of catfishing, because for more than 20 years he had pretended to be a straight man to his wife.

In it Dameron chronicles the lengths he went to to create and maintain a straight marriage through two decades and parenting two kids, and the costs of his closeted years — including steroid and other drug abuse and the searing loneliness that comes from never being able to let yourself be truly seen — before he finally started taking steps, smaller at first and then stronger strides, toward living as himself. (Read an excerpt here on Salon.)

Dameron and I spoke by phone last week about coming out, catfishing, and why we're collectively so enamored with scammers right now. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Let's start with the essay that you and I worked on together for Salon. Can you talk a little about how the idea for it came together?

This woman wrote to me out of the blue, that said, "Your face has meant a lot to me, and now I found out it's a lie." That just sort of shocked me. [I thought] OK, this has got to be spam.

But then, so strangely, the next morning another woman wrote to me on Facebook and said that the same thing happened to her. The first woman had a four year online relationship, the second one was just a quick encounter on PlentyOfFish. But that's when I realized, OK, two people have contacted me within 24 hours. I think there is a lot more to this story than just a one-off.

As I began to get more people contacting me, it was sort of a revelation: "Oh wait, this is sort of what I did for most of my life. I catfished everybody I knew." And that's when it became, in my mind, this really unique and interesting story. I could understand why it happens and how it happens. Not that I condone it, but I had done the same thing.

I thought that that was so fascinating, the connection that you drew between a sleazy online gambit to try and create connections, emotional or otherwise, for scamming unsuspecting people, and your actual act of trying to live as a straight man when you were actually a gay man but hiding that from the world. When did you start to see that these two things were closely aligned in your head?

I wanted to understand why people catfish other people. Because in my mind, that seemed really sleazy. And I had been out for a while [at that point] and I wasn't drawing the connection or the relationship between the two. But I did my own Google search for, "Why do people catfish?" And this quote jumped out at me, which was, "People catfish people because they're uncomfortable with who they are, so they become somebody else."

And that really hit me: oh wait, that's what I did. I was uncomfortable with who I was, so I became somebody else. And that's where the connection formed in my mind; these stories were really related.

Your book is about longing to be an authentic person and not feeling like you can, which I think is a very broadly relatable story, even beyond the specific arena of coming-out memoirs or LGBTQ stories. The book shows how coming out, in whatever form that takes for a person, can be such an ongoing process. Can you talk a little bit about what you learned about your own coming out process from that?

Yeah, and you're exactly right. Coming out is a daily event. We have to do it all of our lives. It's not just a big coming out; just putting your partner, or your husband, or your spouse's name on a form, whatever, we do it constantly. But I think in the catfishing sense, what I related to and what I try to use in my story is the catfishing incident allowed me to look through a different lens at what I did, and look at the people that I fooled, and what impact that had on their lives too. It changed the perspective of the story to not just really center on me, but to center on everybody in my life because they were fooled by what I did just as I was fooled.

I believed the lie that I couldn't be who I was, that it just was not an option. And I think that's really what the angle of the catfishing allowed me to see.

One line that really jumped out at me as being particularly heartbreaking is towards the end when you're talking about how you're falling in love with Paul — who's now your husband — and you describe yourself as, and I'm paraphrasing here, "I was the troll living under the bridge" —

He actually loves that line. The first time I gave him the book, he sat on a plane next to me, we were flying to San Francisco. I had given it to him, he had downloaded it on his iPad, and for days he didn't read it. And of course, I was getting angry —

Typical writer, yeah.

I'm sitting next to him and that's when he started reading it. I was like, "You are not going to read this now." But he did, and when he got to that line, I saw him bobbing up and down because he thought it was so funny.

It's a very poignant moment: you've arrived at this point where you're in a relationship with a man you really care about and you're living your truth and yet, at the same time, you still have that voice that's telling you that you are not worthy of the love that you could have, that you're not desirable, that there's something wrong with you just as you are. That you still need improvement. There was the other line that you said to Paul: "But I have potential." Did you see this as a story of not only coming out in a traditional sense, but also a coming around to yourself?

I think when you live as an imposter and you question yourself for so long, it becomes muscle memory. And even when you get to the really good stuff — here is this wonderful relationship and this man who so clearly loves me — you still question yourself. It's not that you're not being authentic, you question if you're valuable enough to be loved, you question if he's just doing it because he's nice, and you question your own beauty because you can't see it. It takes a long time to get to that point, to where you stop putting this person up on a pedestal.

You have to lift yourself up. It's tough. I think that's hard for people. On social media, we always display the really pretty side and the good side, and I think the big reason we do that is because we're insecure. We want to show our good, valuable, pretty side. It was, for me, a process of getting to that point where I can still be attractive when I'm unattractive, to the right person.

Has Katherine, your ex-wife, read it?

You know, that is a question that I get pretty often. I did not send her the book and I didn't want to force it on her. I don't know if she has. I know she has read some of the other things I have published. And I certainly did talk to her and let her know what I was going to write and what I was going to publish.

My hope is that she does read it because I devote a lot of the book to trying to make amends and expounding upon what forgiveness is. It's not something that we can just take. Forgiveness is something that one person does, it's not a two person thing. I can say I'm sorry, but forgiveness is something somebody else uses to help them get through the maze of all of their feelings, to let go. So, I hope she does. I hope she does read it, when she's ready to.

On the theme of forgiveness, your relationship with your mother goes through a big arc throughout the book, starting with how much of the deep rooted shame and secrecy that you went through was due to her reactions to you as an adolescent, when she thought that you might be gay. And then she came around later in life, having relaxed so much. I thought that it ended on this really amazing moment of grace, where you really see your mother as a person, not as your mother, which is a hard thing I think for any person to do, right? To see their parent as just an individual person who has had longings and disappointments just like they have. And that forgiveness that you grant her in that is really powerful.

I'm interested in forgiveness right now because we seem to be in a moment, culturally, where forgiveness doesn't seem to have a lot of currency. Why do you think that is?

Yeah. Because everybody wants to be right and everybody thinks they're right, and that their version of the truth is the only version of the truth. I've learned through the process of writing this memoir that even when people act cruelly, there's some motivation behind why they act that way. I don't think as a society, we really try to dig behind that motivation. We just look at what this person has done, and [say], "You're wrong." And that's all there is to it.

My mother does have a definite narrative arc in this book. It shows that people can evolve and that was so important to me to bring that point out, because I think it's so important for society today. We want to believe that people are one way, and that's the way they're always going to be. But we can evolve and we can get better.

I was worried about how my mother would react to this book because she does start out as the person who shoves me back into the closet. But I had to look and see why she did that; she thought she was protecting me. And in the end, she becomes my biggest ally.

I gave her the book. It took a while for me to get it to her. I actually sent it to her, and I didn't mean to do this, like, a day before Mother's Day.

I was texting my older brother, like, "Is mom going to read the book?" And he said, "She's reading it now." I'm like, "It's Mother's Day. She's reading it on Mother's Day?"

She got to the end and she sent me the most beautiful note that she loved it and she understood me better and she loved me even more. So, the book was successful just from that standpoint.

As a culture right now we are really enamored with stories of scammers. Like Anna Delvey, the woman pretending to be the heiress who's just taking all of these folks for a ride. As someone who's thought deeply about catfishing, why do you think that we're so obsessed, culturally right now, with the high-profile scammer?

I feel like in a way we always have been. Cyrano de Bergerac, he was a big scammer. He had Christian deliver his notes to Roxane, they used this real person's face. I think as a culture, we've always been enamored with scams because I think we all do it. We do it all the time.

We're doing it more through social media, but we're sort of always scamming. And maybe we feel like we're always a little bit of an imposter, and wonder what we can get away with. We all sort of dream of being a movie star or becoming a big celebrity or whatever. I think that's just a persona that people put on.

But I think too, I mean, let's look at the current administration. Everybody who's in it should not be in it. They've all scammed us.

"Grifter" is the word that's often applied there.

I was a bit worried, I have to tell you, about telling my story and then calling it, "The Lie," because it seemed to me so negative. But I wanted to lift the veil because there's so much written in so many stories about men or women who are in the closet and married to a straight partner, and everybody sort of gives this sidelong glance, "Yeah, he's gay. He just doesn't know it yet." It's almost like it's a joke, you know?

Yeah.

But there's so much pain and anguish beneath that façade, and I just wanted to tell that story. There's a whole generation of people who went into the closet, made this promise, when there was no option to be gay, and they're still stuck in this promise. They built their whole life on it. And how do you take the sledgehammer and destroy all that? I hear from them every day.

You do?

Yes. I get emails from so many people. I got an email from a woman who was married for 24 years, had four kids, and then she came out. We were all stuck in that closet, the world changed, and we didn't know how to get out of it.

I feel like it's quite possible now that there's a whole generation of adolescents who are maybe bewildered by the idea that a gay man would choose marriage to a woman instead of coming out and living as a gay man.

Exactly. And when I looked, I could not find a book like this. I couldn't find a memoir that detailed the queer parent perspective who's been in the closet. And I think it's important for kids to know that. Because I know some kids think when their parent comes out: Was I just this mistake, or disguise? And that's never the case. I mean, I loved and love my ex-wife. I certainly love my kids. I wanted to have a family. As a gay man in the '70s and the '80s, it just wasn't possible.

Another thing that stood out to me about this book is an integral part of your path to healing and to learning how to live as yourself out in the world, was your therapy group that you became part of. You described it as your first actual group of real male friends?

Yes. Yes, and they still are.

Are you still close with them?

Oh, yeah. Yeah, this is going to sound so stereotypical, but we have what we call a "Sex and the City" night where we get together and we go out.

There's been a lot written lately — and this is mostly about straight men, but masculinity and the potentially stifling effects of it is obviously something that affects queer men as well — about how men have a harder time building authentic, real, honest friendships with each other and that it has damaging mental and emotional health effects on them. How did your life change once you realized you had a whole group of close male friends that you could rely on?

It was amazing. You're right, because I never had a true close male friend because my masculinity was so toxic, it was nearly fatal. Literally, because I did the steroids so I could become somebody else.

After I did group therapy, and it was six of us in a room in chairs, it was eye opening that I could be friends with other men and we could talk about things that I never could talk about before, that I could never express. And it's life saving. It really is, to have true friends who really know you. I didn't realize how damaging it was to be so caught up in masculinity, that I couldn't see that.

And it's more than just having the male friends, it's just a daily activity of enjoying life and all of the things that I thought I couldn't enjoy before like going shopping, or clothes, or ... it was even down to like, "OK, I can't cross my legs because that looks gay." When you're always concerned about being labeled as gay, you can't enjoy life. But now, if somebody says, "Oh, I think you're gay," I take it as a compliment.

Before we close, I did want to ask you a question about your work.

I'm an IT Director for an economic consulting firm.

So, one of my big responsibilities is making sure that all of our data is safe because our inventory at work is data, it's the results and analysis that we do.

I've been following the threat of not just deep fake videos, but now there are so-called deep nudes — there's an app that you can buy that can take a photo of a person wearing clothes, and algorithmically create a nude version of them. The ramifications of that are scary. Have you seen this yet and had any thoughts on the rapidly evolving uses of fraudulent photo use online of actual people?

I have not heard of that, but I'm suddenly very terrified because you know, my face has been used before. Now it might be my entire body that's used.

But yeah, I think artificial intelligence is being used so much now, not only with creating the fake nudes that you were talking about, but in recognizing faces. And actually, I think I've heard of some that can analyze a face and tell you whether that person is gay or not, which is also a little bit terrifying.

So what I do at work, I always try and educate our users so that they won't be duped. It works out perfectly for me because I always use my essay now, and I always go back and say, "So, who here has an iPhone? Okay, I want you to look up 40 year old man selfie," and they do that, and they see my face. They look at the phone, they look at me, and they're just like, "What?"

And so, I tell them, the way we're going to get hacked is somebody who's going to pretend to be somebody they're not. You're going to trust them and give them something you shouldn't. So that's it. The number one threat is social engineering, in both a personal and professional way.

Shares