On any given day, the contents of Thomas Jefferson’s fridge could blow away that of any Mario Batali restaurant. The president allocated more than $16,500 to wine during his two terms from 1801 to 1809 and, according to the head steward, up to $50 a day for food. (Economists at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics loosely estimate that Jefferson’s $16,500 wine bill would run between $300,000 to $350,000 in today’s dollars and his $50 daily food allowance close to $1,000.)

The kitchen and underground brick wine cellar, nicknamed the “ice house,” were replete with partridges, wild ducks, courtyard ducks, venison, squab, goose, pâté, rabbit, squirrel, crabs, and oysters. One of Jefferson’s servants back at Monticello, his renowned Virginia palace/slave prison, recalled that Jefferson “never would have less than eight” courses even when dining alone.

His wine collection grew to twenty thousand bottles. A typical monthly order would include 630 gallons of Madeira, one barrel of sherry, 540 bottles of sauterne, and 400 bottles of claret. In 1804, Jefferson’s champagne bill alone racked up to nearly $3,000—probably enough to buy five whole black people. But did the president ever reel from sticker shock? “Let the price be what it has to be,” Jefferson wrote to a wine merchant.

Smooth operator that he was, the revered “Sage of Monticello” would not allow his weakness for delicacies to contradict his politics. A populist who believed in decentralized government—an agenda contrary to that of his predecessors, George Washington and John Adams—Jefferson recognized the need to rebrand his penchant for loins of veal and 1785 Bordeaux. He influenced American dining trends with a revolutionary atmosphere that didn’t call for awkward toasts and uppity dress codes. Imagine a scene comparable to a rustic chic bistro in ritzy modern-day Brooklyn: multiple oval-shaped tables, spread throughout the room and without seating assignments (versus, say, your typical bowling alley–length table, found at WASPy Thanksgivings). Jefferson’s guests would serve themselves and clean up afterward, as if dining at a poorly staffed Chipotle.

“He didn’t want a servant at every elbow,” said Susan Stein, a senior curator at Monticello. “At the president’s house and here at Monticello, he had dumbwaiters, which allowed people to remove their own soiled plates and stack them. It was a friendly atmosphere where people commented on the conversation. It was about ideas and discussions. It was about intellectual vitality.”

Often clad in his bedroom slippers, Jefferson was known to ladle meals onto his guests’ plates, at least for those seated in his immediate area. Whenever a bottle needed opening, he would brandish a custom pocketknife, which included a corkscrew. But don’t judge a man by his booze tools. Jefferson’s drinking was moderate at best: three glasses per night, or, as New York wine merchant Theodorus Bailey observed, he drank “to the digestive point and no further.” His preference was usually to imbibe after the meal—a haughty trick he picked up across the pond.

In 1784, five years before Washington’s inauguration and more than a decade before his own, Jefferson was appointed U.S. minister to France. For five years, the six-foot-two ginger rubbed elbows with Europe’s political elite while filling up on fine wines and rich cuisine. As one might imagine, it was not a horrible five years. At the time, Jefferson ate better than pretty much anyone in American history (at least until the advent of truffled macaroni and cheese). He collected silver, paintings, china, and sculptures to adorn Monticello and transformed himself into something of a connoisseur.

Oh, and he appreciated more than just what Europe offered in the way of fine arts. Unlike his prudish colleagues back home, Long Tom didn’t get his cravat in a knot at the sight of prostitutes. If anything, the international man of mystery admired those individuals committed to the world’s oldest profession.

“St. Paul only says that it is better to be married than to burn,” he wrote in 1764. “Now I presume that if that apostle had known . . . to furnish them with other means of extinguishing their fire than those of matrimony, he would have earnestly recommended them to their practice.” Fast-forward to 1784, and one can imagine Jefferson’s excitement when he discovered the Palais-Royal—Paris’s newly renovated entertainment complex, inhabited by cafés, bookstores, gambling, and, when evening came, a pack of hot-to-trot call girls. Jefferson considered it one of the “principal ornaments of the city” and had hopes that the business community of Richmond, Virginia, would replicate it. (If only they had listened! “What happens in Richmond . . .”)

Despite his enthusiasm for the sex trade, no evidence suggests Jefferson ever indulged—and why would he bother, when he had a gaggle of comely slave women at his disposal? In 1787, a half-black teenager named Sally Hemings arrived in Paris to serve the forty-four-year-old statesman. Described by Jefferson’s grandson as “light colored and decidedly good-looking,” Hemings was also the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife, Martha, who died from childbirth complications five years prior. The teen slave attended to the widower’s daily needs—yes, those needs—in exchange for clothing, medical attention, and 12 livres a month, which today could buy you a one-week trial membership to a yoga studio. Upon their return to the U.S., while the diehard romantic would serve presidents Washington and Adams as secretary of state and vice president, respectively, Hemings would bear six (!) of his bastard children. (He also had six children with Martha.)

Indeed, five years in Paris will class up just about any old Southern farm boy.

The years inside “the president’s mansion,” as the one-year-old White House was known back in 1801, hardly measured up to Jefferson’s good times in the City of Lights or his lavish retirement at Monticello. Hemings did not travel with her master to the city of Washington; she remained in Virginia to care for the plantation and her sextet of illegitimate children. Meanwhile, as commander in chief, Jefferson wrote that he and Meriwether Lewis, his personal secretary, lived like “mice in a church” inside the “great stone house” that was theoretically large enough to fire Munchkins out of a cannon without the neighbors bothering to notice.

Afternoons were quiet enough. Jefferson spent the better part of ten to thirteen hours each day at his writing table, grumbling over policy or, more enjoyably, reading the latest literature on wine or the arts and sciences. Anatomy in particular interested the president. One room in the mansion was reserved for his fossil collection, an assortment of tusks and skulls “spread in a large room,” Jefferson once bragged, “where you can work at your leisure.” In the evening, he would abandon his desk for “riding, dining, and a little un-bending,” successfully avoiding the bear cubs he kept in the yard for a couple of months in 1807. Throw in some Elvis memorabilia and Macaulay Culkin, and Michael Jackson would have felt right at home.

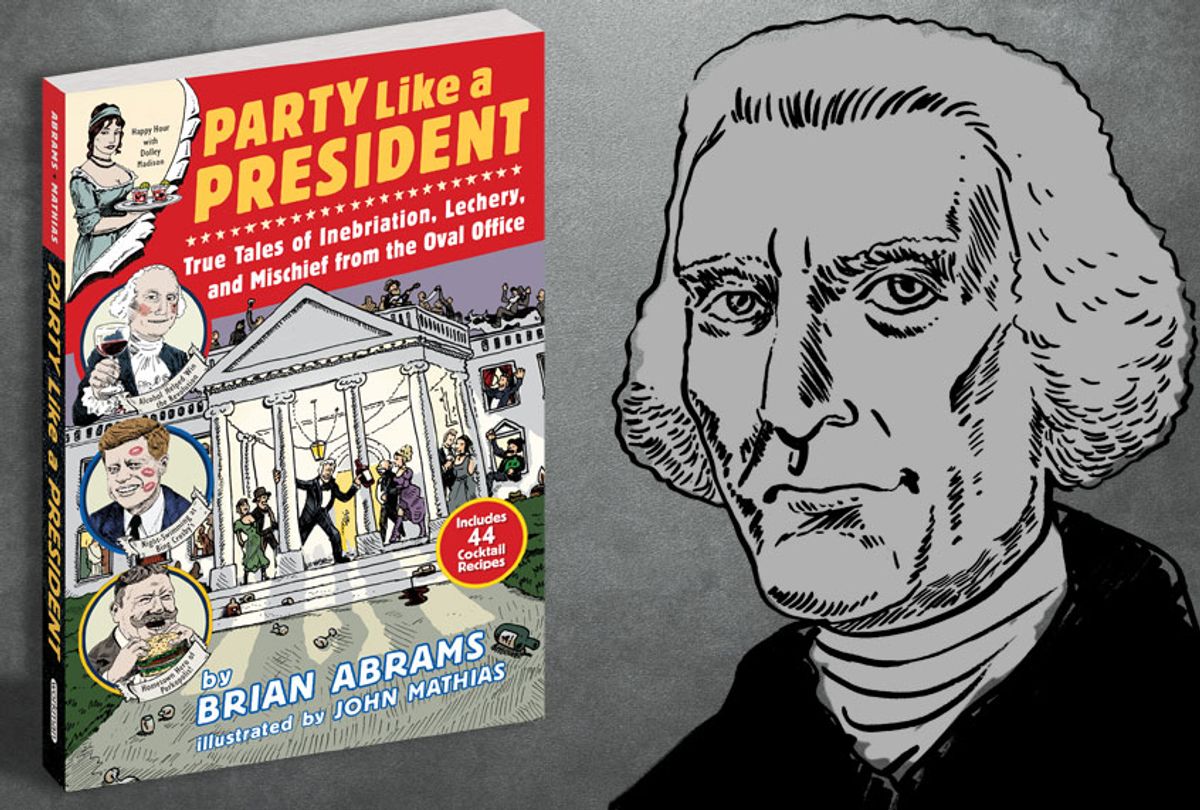

White Wine Spritzer

During Jefferson’s retirement at Monticello, one of his granddaughters recalled a picnic in which he oddly “mixed the wine and water to drink with it.” Leave it to one of America’s first foodies to experiment with what was presumably a prototype for a light and refreshing summer cocktail.

dried strawberries, chopped

strawberries

white wine (Sauvignon blanc or Gewürztraminer varietals recommended)

soda water

Store the dried, chopped strawberries in the freezer ahead of time to use as ice cubes. Muddle the fresh berries in a bowl with a fork until the consistency is all pulp and juice. Fill a glass halfway with wine, then top with the strawberry pulp, a splash of soda water, and berry ice cubes.

Shares