When most people think about the Apollo space program, and the people behind those historic missions, a slew of white men might come to mind: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, Jim Lovell — the astronauts who went to the moon. But as Frances "Poppy" Northcutt told me in our interview, just as it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to take someone to the moon, too. “The teamwork that was involved is one of the most incredible things about Apollo,” Northcutt told Salon. “The extent of the team — people don't understand that team wasn't just what you saw on TV.” Rather, it was about 400,000 people spread all around the world, she explains.

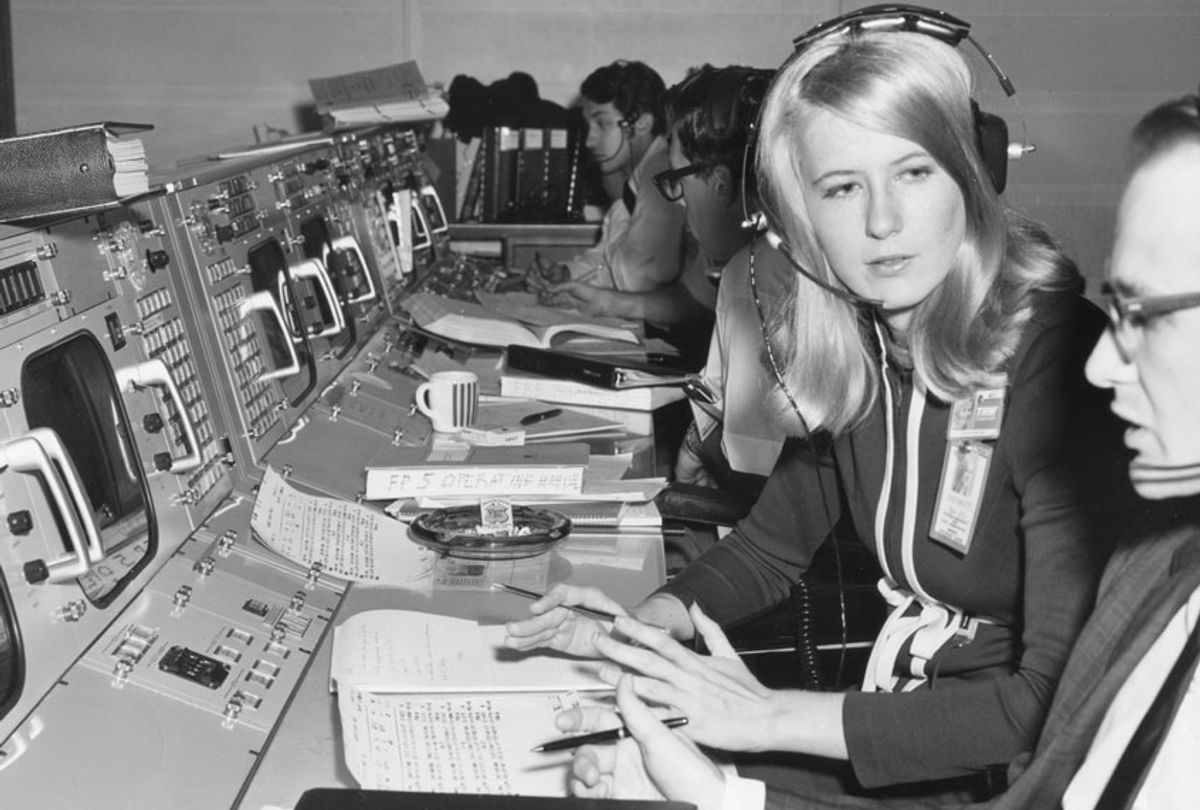

One of those 400,000 was Northcutt herself. As the first woman to work in Apollo's Mission Control Room — as an engineer — she was responsible for calculating return trajectories for Apollo 8, the first mission to leave Earth’s orbit and circle the moon. Among other missions to the moon that she worked on, she famously helped retrieve the Apollo 13 astronauts after a mid-flight disaster. But you would never know a woman was behind that from watching the 1995 Hollywood movie about that near-deadly mishap. Northcutt's erasure from "Apollo 13" embodies how women who were paramount to the Apollo moon missions were confined to the background for decades.

Fortunately, thanks to films like "Hidden Figures," that story is changing today; indeed, there has been a critical reevaluation, as it were, of the role of women in the lunar missions as we approach the first moon landing's 50th anniversary this July. A new National Geographic documentary, "APOLLO: Missions to the Moon," which premieres July 7 on the National Geographic Channel, weaves together more than 500 hours of footage, 800 hours of audio and 10,000 photos to tell the most immersive account of NASA’s Apollo Space Program. In it, Northcutt is part of the archival footage, photos, and audio, which pieces together an inclusive Apollo story.

In June, Salon sat down with Northcutt in San Francisco to talk about what it was like being a woman and working for the Apollo Program, what has and hasn’t changed in STEM today, and what barriers women continue to face in male-dominated fields.

Editor's note: As usual, this interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Nicole Karlis: Thank you, Poppy, for making time to speak with me. We are really excited to talk to you and learn more about history, space, and your thoughts on gender inequality in the science and engineering world. But first, I was hoping you could share with our readers how you became the first woman to work in the mission control room — especially since, at the time in the 1960s, it wasn't really a traditional path.

Poppy Northcutt: It was a very non-traditional path for a woman. It was an accident. It was a product of being in the right place at the right time. You had to be prepared as well, but it was really a complete fluke.

I worked for a contractor to NASA, [for a company] named TRW. TRW is now part of Northrop Grumman. But at the time I worked for TRW, and we had a contract with the mission planning and analysis division of NASA. Our contract was to develop a family of computer programs that could do trajectory analysis and design for a variety of maneuvers. It would be used in the Apollo program — lunar reinsertion, which put the orbit around the moon. Trans-lunar injection to take them on a path to the moon, trans-Earth injection to bring them home and mid-course corrections.

I worked in particular on trans-Earth work. We developed this family of programs, and they accelerated the schedule on Apollo 8. That was sort of the precipitating thing about why we ended up over in the control center. We were so concerned about the Soviet Union beating us to the moon that they accelerated the schedule. Our program was, obviously, critical. You don't want to go unless you could get back, and they [NASA] were completely unfamiliar with it. So, we were asked to go over there and help get them up to speed on using the return-to-Earth capability. It was not something that we expected to be doing. We're just suddenly called upon, "Hey, we want you all over there." So, we went.

I had no idea at the time I was going to be the first woman in mission control. I knew there weren't many women over there, that was for sure. That was fairly obvious. But, I didn't know I was going to be the first. I figured that out pretty quickly.

Wow, so it was a byproduct of the fear of the Soviet Union winning the space race. And that meant putting the first woman in the mission control room.

Yes, that wasn't the choice that they were making. It was just a byproduct of that pressure to try to get up to speed pretty quickly because trying to come back to Earth from the moon is a whole different kind of thing than trying to come back to the Earth from the Earth orbit. So, we went over there. When we first went over there, we actually sat next to the officer in mission operations control room, which is the big one you see on TV. That was the public feed that you would see.

During the flight itself, we sat in the back room. We sat in a bunch of back rooms. We sat in the staff support room one, SSR1, which is about 20 feet from that big room you see on TV. It would be one of us from the developing program. There were usually two of us. We would alternate time, plus someone from mission planning and analysis. We were there for [Apollo] 8, 10, 11, 12, 13.

Some pretty historic ones. Can you describe what an average day was like in mission control room, just from your perspective?

Well, there's two different ways to look at it. I mean, one way is you simulate. A whole lot of the time is to simulate. We were still working our regular work, which was really located across the street. We're not in the control center all the time. When we were not in flight, we were basically across the street doing what we did, which was development of future programs, and tests and so forth. Then, we would go over for simulations if they involved center of operations. During missions, themselves, I would come over there once they got probably about 50 something hours into the mission. Once they got close to the moon — then, I would be alternating, probably working 13-14 hour days, alternating. We only had one other person I was alternating with. Then, we would also do double coverage during what we knew were going to be critical maneuvers. So, we would have double coverage during the insertion, and we would have double coverage during trans-Earth injection.

It was an alternative reality to work in there. Everything is on mission time. You lose all track of regular time. When you walk out of the building, you have no idea, "is it going to be night? Is it going to be day?" You have no clue. You're like, "Oh, it's daytime. How bout that?" So, it was just a very surreal experience to be over there. Everyone is completely engrossed in the mission. You don't know that anything else exists, because it doesn't. By definition, it doesn't.

Did you go on weekends?

When you're on a mission, you're on a mission. Okay? Like I said, there is no other time. There is no "weekends." There's no night. There's no day. There's nothing but mission time. You're there for when you need to be there for the mission.

Sounds exciting.

Well, it's completely engrossing. The other thing you learn to do is you compartmentalize everything. So, in addition to the rest of the world being outside, you focus entirely on what you do. You're not worrying about what these other people do. That's not your job. You know you're thing, and you just trust that these other people know their thing that they're focusing just as much on their thing as you are on yours.

Right. In the hope that it all comes together, flawlessly.

And amazingly enough, it usually did.

Yeah. That's really amazing. Was it different for you in that environment as a woman?

Well, by the time that I went over there, I was used to being the only woman in the room, because I worked for a more progressive company, in my opinion it was more progressive than NASA was, but it was still the 1960s. If you were a woman in that world, you were used to being the only woman in the room. So, it wasn't really that different when I went over there. But they were all surprised there was a woman in the room.

I remember one time, we had headsets on, and we would listen to four or five different things. You could tune in to a whole bunch of different things. That was one of the challenges when you first went over there, figuring out, "How do I figure out what I need to listen to? What I don't? How do I tune this in and tune this out?" We also had these consoles where you can see different channels. You could call. I would, during the simulations on Apollo 11, I would hear some chattering on about "Hey, look at what's on channel," whatever it was. I heard that several times, but I was busy. But, one time I heard it and I thought, "I wonder what is on channel whatever that I keep hearing these guys talk about."

So I turned onto that [channel] and it was me. It was a camera that was focused on me. That was pretty off-putting. You know, of course the first thing that comes to your mind is, you're going, "What are they doing? What have I been doing when this hidden camera's been watching me?” But, I just, I wouldn't have known who to report it to, and I probably would not have reported it. It wouldn't have been good to report it. It would've made things worse instead of better. So, I just ignored it and remembered, "Hey Poppy, there may be a camera that's watching you this whole time." They had cameras in all the rooms. It's not like there weren't cameras. You assumed the room was being photographed. But, this camera was homemade. It was not in the room. So, I knew I was being watched. At that point, you can't not know it. So, you just let it fly and go on.

That is definitely off-putting, to put it lightly. I want to hear more about what it was to be the only woman in the room at that time. You mentioned that sexism in the workplace wasn’t really something you could report back then.

Well, especially, because what you want is you want to be integrated. You want to be accepted into the group. The last thing that's going to get you accepted at that time would've been to make a scene about something like that. Far better to just shake it off and move on. And, recognize that they're going to get tired of this. Yeah. They'll get tired of this. I don't know how long that lasted, but I just figured once they get over the surprise of knowing that there is this alien in their midst, they'll move on.

Did you ever face sex discrimination as it related to your very role in the Apollo missions at NASA, and did it ever affect you from doing your job?

No. No. They never impacted my role. As I said, most of the guys that were there, they were more interested ... everybody's focused on the mission. Okay. While some of those guys were ... those guys that were doing that thing with the camera I don't know exactly who they were, but I dare say that probably in some back room somewhere. They were in that basement, in that real time computer complex, wearing some other stuff, but it was really just the attitude of, "Oh there's your mom in there." I think part of it is because they knew they needed help. They knew they needed help. They knew that the return to earth program was critical. They knew that they needed to know this. And, they knew that I was someone who, I knew my shit.

What was it like being in the mission control room during Apollo 13? I'd like to hear the whole story of Apollo 13 as well, since you played a very critical role in that.

Well, Apollo 13 to me was the most successful of the Apollo missions. Not because it met the mission goals, because it didn't, but because we met the ultimate goal, which is to get them home alive. And, we did so under the greatest of adversity. We did so proving we could recover from a disaster. I think there's ... I mean, what could be a bigger showing of your strength than to recover from a disaster? It was a great success in that sense.

In terms of what I did in the return to Earth function, we actually were not particularly challenged. That was what we did. That was our whole purpose, you see. Our program was initially called the abort program. It was actually designed for aborts. It was not designed for nominals. It is designed for aborts. It ended up being used for nominal missions, as well as abort situations. It was designed to handle the emergency. And, it worked exactly as it was meant to. Even the use of the descent propulsion in the system, was something that was painful. We had suddenly needed that. That was a contingency that we were prepared for. We had prepared to use the accent propulsion system, the descent propulsion system, both of them combined in order to come home. For us, it was a very gratifying thing to see that this worst case scenario, we could handle that.

Was there any moment that you were really panicking though? Or, no?

No. The most scary mission as far as I was concerned was [Apollo] 8, because there were so many in that, and because they were going to do these critical maneuvers on the back side of the moon, with no communication. That was really heart stopping. Now, I don't mean to say that 13 was not scary. The thing that was scary about 13 was not “can what we do work?” I had complete confidence. We knew how to do that. The unknown for us was, what is the condition of the spacecraft. That was really the unknown for everybody. We thought we knew this, that, and the other thing, but did not really know. They didn't really know much about the true extent of the damage until separation. They come back. As they get close to the Earth, they separate to re-enter. At that point, they've got a view of the backside of that spacecraft and find out that a lot of it was gone.

What is one lesson that you learned from all of the missions that you still carry with you today in your life?

I learned a lot of lessons.... I learned a lot about sex discrimination, that nobody taught me in school. They didn't teach young women that then, and they probably don't teach them now, about what all can happen, in terms of all of the various ways in which you can be discriminated against. I learned about how protected legislation doesn't protect women. It exploits women, keeps us from being able to control whatever. These days, they're keeping you from controlling your own body, but in those days, they were controlling your income. I learned that within the first few months of being in the workforce, because I had the wage hour laws being applied. It was not my employer that was doing this to me. It was my male-dominated state legislature, saying I could not ... well, they would say I couldn't work more than 9 hours, 54 hours a week, but what it really boiled down to was, I couldn't be paid more than 9 hours, 54 hours a week, by one employer. My employer was not making me work more than that. My employer was coming by and saying, "Look Poppy, you know we cannot make you do this." That was not protecting me, because if I wanted to work three jobs, I could've worked three jobs, but the difference was, I wasn't going to be able to get overtime. Overtime was a big deal.

Right, because you were working 14 hour days.

Yeah. I mean overtime was a big deal. It also worked not just to take money out of your pocket, or prevent you from earning this money. It also worked in a way that separated you from other people. If you're an employer, are you going to want to give the job to somebody who's going to be able to work the whole way, or are you going to want to give the job to somebody who's crippled, in a sense. You know. Working with one hand tied behind your back. It also prevents you from becoming a member of the team, because to be a member of the team, you have to work like the team. You can't be the one who always goes home. The rest of the team's working 12 hours and you’re leaving at 9. How are you going to really become a full member of the team.

I did not pay attention to those laws. I just went. My boss would come around and say, "You know we can't pay you." I'd say, "I know that. Okay? I'm staying." I worked the hours. I think that was a big reason why I ended up getting promoted and other people that were "computeresses" — that was my job title at the time — did not. Is because I just knew that I had to do that in order to be a member of the team. But, you never get that money back. Ever. You know, it means you get a lower retirement, when that comes around. It just snowballs and travels with you, those pay disparities, throughout your whole life. I was very fortunate. I mean, I was. I was very fortunate. I earned more money than most people did. There were women, at the time, but the effect of that kind of stuff, on women, is just devastating. So, I learned a lot about discrimination.

What else did I learn about? I learned a lot about testing. That's been a very useful thing to know, too, because there's all kinds of things in your life where it's a good idea to test. Okay? Not necessarily in the same sense of doing software testing but, it's the same principal. I think there's three rules of testing. One rule is figure out what the tests of assumptions are. You've got to figure out what the tests of the assumptions are. Then, you've got to test all of your assumptions. Then, you've got to push things to the limit and find out when it's going to break.

You ended up becoming really involved in the women’s rights movement after NASA. That doesn't seem like a coincidence. What was your transition out of NASA like?

Well, we lost our major contract with NASA. I worked on missile weapons systems, which I hated. Part of that is because in the space program you're working on something, you can hardly wait for your product to be used. You can work on it for years and years and years. Sitting there going, "I can hardly wait for it to be used." But, you work on something like, any ballistic systems. I mean it's the biggest nightmare in the world. So, it's just a feeling that you have about your work.

So, I went back to Houston. I was put on the mayor's staff. I worked for the mayor, and having been on the mayor's staff, I was very involved in trying to improve the status of women in the city, increasing the number or women on board, to commissions and so forth. I just became more and more aware of the barriers that women faced in the workplace, and in society as a whole. I had already become active in the women's rights movement. So, I decided to go to law school. I clerked for a federal appellate judge, which was a great experience. But, I also entered the district attorney's office, which was very challenging. I loved being in the courtroom. I loved the stress. I guess I'm a type-A personality, because I like pressure situations. I enjoy doing trial law. I also had done appellate work.

So, I just enjoyed all of that stress and craziness that you get. The challenge of everyday ... what you deal with in criminal law is sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll. That's it everyday. So I really enjoyed that. But I always did something to work on women's rights. When we were setting up a domestic violence unit, I went over as the first felony prosecutor in that. That was a real education. I didn't know much about domestic violence. I found out a lot of stuff I didn't know, still don't like knowing, but better to know it than not know it. I'm still active in women's rights, including reproductive rights.

How can we bring true gender equality to the STEM space?

Well, the more women are involved, the more women are going to ask. Part of it is that we have to continue to recognize the importance of including women in all of these jobs. As a social system, one of the things we need to do is that we need to try to be conscious of how we're treating boys and how they're treating. Instead of always focusing on the appearance of girls, focus on how smart girls are. Get the girls themselves to think about themselves in those terms, about what's really important. It's my brain. Okay? Not how skinny is my waist, not the makeup I'm wearing, but my brain. That would also affect the perception of men if we do it like that.

Final question: In the spirit of the anniversary of the moon landing, what you think of people who think that the moon landing was a hoax?

You know there's this thing called confirmation bias. It's a real thing. They want to believe that, so they're going to believe it. However great the pictures may be, they're still going to believe it. However great, I mean, whatever, they're still going to believe this, because that's what they want to believe. I don't know what else to say about that. We would be talking about a really remarkably amazing hoax. We'd be talking about a hoax that involved 400,000 people, at least. That's a really complicated hoax. Now, do we actually think that our government is actually clever enough to pull off that kind of hoax? Even if they wanted to do that kind of hoax, I just don't think my government is smart enough to do that degree of a hoax. I haven't seen it in other things, that kind of cleverness, that kind of focus. You'd have to be really focused and really thorough.

Poppy, you are such an inspiration — thank you for your time.

Thank you!

Shares