Kepler, a planet-hunting space telescope, has looked at half a million stars, but nothing like HD 139139. After a year of analyzing data from the now-retired exoplanet observatory, scientists still don’t know what to make of one of its observed stars.

“We’ve never seen anything like this in Kepler, and Kepler’s looked at 500,000 stars,” Andrew Vanderburg, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin and co-author of a new paper on the star, told Scientific American.

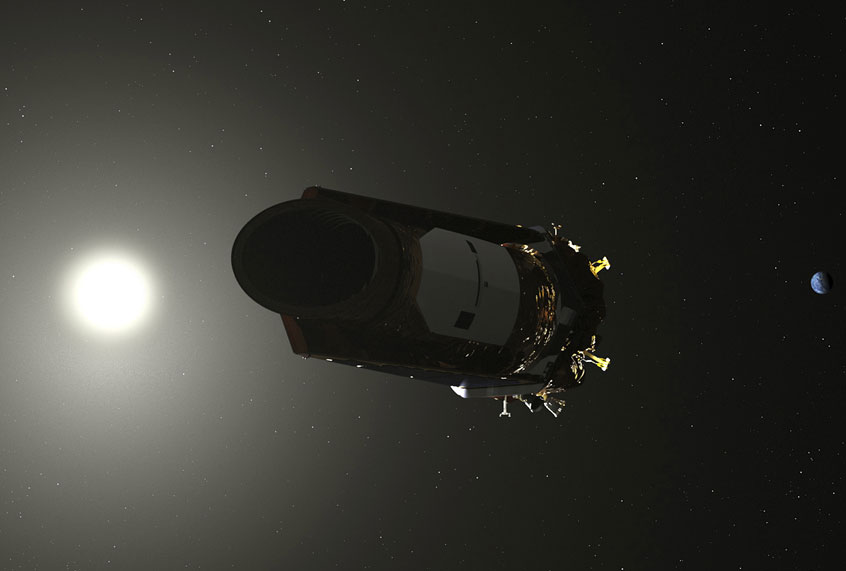

Kepler, a space observatory designed to discover Earth-size planets, was launched in March 2009. The mission was initially expected to last until 2016, but in 2012 one of the spacecraft’s reaction wheels stopped turning. In 2013, a second wheel displayed a malfunction, thus hindering the completion of the mission. Luckily, scientists and engineers figured out a way to reimagine Kepler’s mission in light of its limited mobility; the second, modified phase of its mission was dubbed “K2,” which ended its mission in October 2018.

Today, Kepler has, according to NASA, discovered 2,343 confirmed exoplanets. The K2 mission phase found 309 additional confirmed planets. Moreover, the data collected has enabled volunteer citizen scientists to discover more of what computers could not detect as they sift through the information.

According to Scientific American, in the spring of 2018, some citizen astronomers contacted Vanderburg and brought HD 139139 to his attention.

“When I got that e-mail, I looked more closely and said, ‘okay, this definitely looks like a multiplanet system. But I can’t find any [planets] that appear to line up,'” he recalled.

What makes HD 139139 so perplexing is the amount of light it emits, and the behavior of that light. According to observational data, the amount of light emitted dips periodically, which generally indicates something is occluding the star — generally, a planet, or another star. Observations of these light dips are a common means of detecting exoplanets orbiting distant stars, as they dim in predictable ways; however, what is most perplexing about HD 139139 is that its dimming is not predictable nor does it adhere to conventional models of how orbiting planets should occlude stars. Specifically, the distant star had 28 periodic dips in light which each lasted between 45 minutes and 7.5 hours.

In order for these odd, irregular light dip spans to fit a solar system model, the star would have to be surrounded by at least 14 planets — and as many as 28. If true, that would mean it had far more planets than any known solar system. Judging from the data on its light curves, the planets would all be nearly the same size, specifically, a little bigger than Earth.

The report also suggests a second theory: that the star was being tugged gravitationally, causing a delay on their eclipsing. Yet after observing the star with ground-based telescopes, the team found no indication the star was being tugged.

Perhaps the wildest theory was left out of the paper: an extraterrestrial mega-engineering project that is blocking the star’s light. Previously, that explanation had been proposed as the explanation for a different star’s bizarre light-dipping pattern.

“When people in our community hear about something like this, the running joke is it might be aliens,” Vanderburg said in Scientific American.

Astronomer Tabetha Boyajian at Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge says all options should be considered before jumping to aliens.

“This is one of those systems where it’s probably not going to be figured out without more data,” Boyajian said in Scientific American.