One might have thought that the election of celebrity businessman Donald Trump would have put an end to the stale old trope that we'd be better off if "the government were run like a business." It's a silly idea since the American government's only resemblance to a business is the fact that it employs a lot of people to do certain tasks and, like most big organizations, it's managed in a hierarchical framework.

Other than that, they are very different systems with very different purposes. The most important distinction being that a business is an autocracy which exists to make a profit while the government is a democracy which is, as the U.S. Constitution puts it, organized to "establish Justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity." These are not the same things.

This is not to say that there isn't plenty of profiteering in government, or that some leadership and organizational skills aren't transferable. But the fact is that government, family, religion, criminal enterprises, business, etc., are all human organizations. To say that being successful at one automatically means you would be good at executing the duties of the other is absurd. Yet the idea that a great titan of industry or an entrepreneur or tycoon would be better suited to run the government than a politician is a long-standing myth in American life.

This has remained true even though the 20th- and 21st-century businessmen who became president have largely had unsuccessful presidencies. Warren G. Harding was a newspaper publisher whose presidency is best remembered for the Teapot Dome bribery scandal. Mining executive Herbert Hoover presided over the Great Depression. Peanut farmer Jimmy Carter and oilman George H.W. Bush were one-term presidents, while and oilman and Major Leage Baseball owner George W. Bush gave us the Iraq war debacle and the Great Recession. It's not a great record.

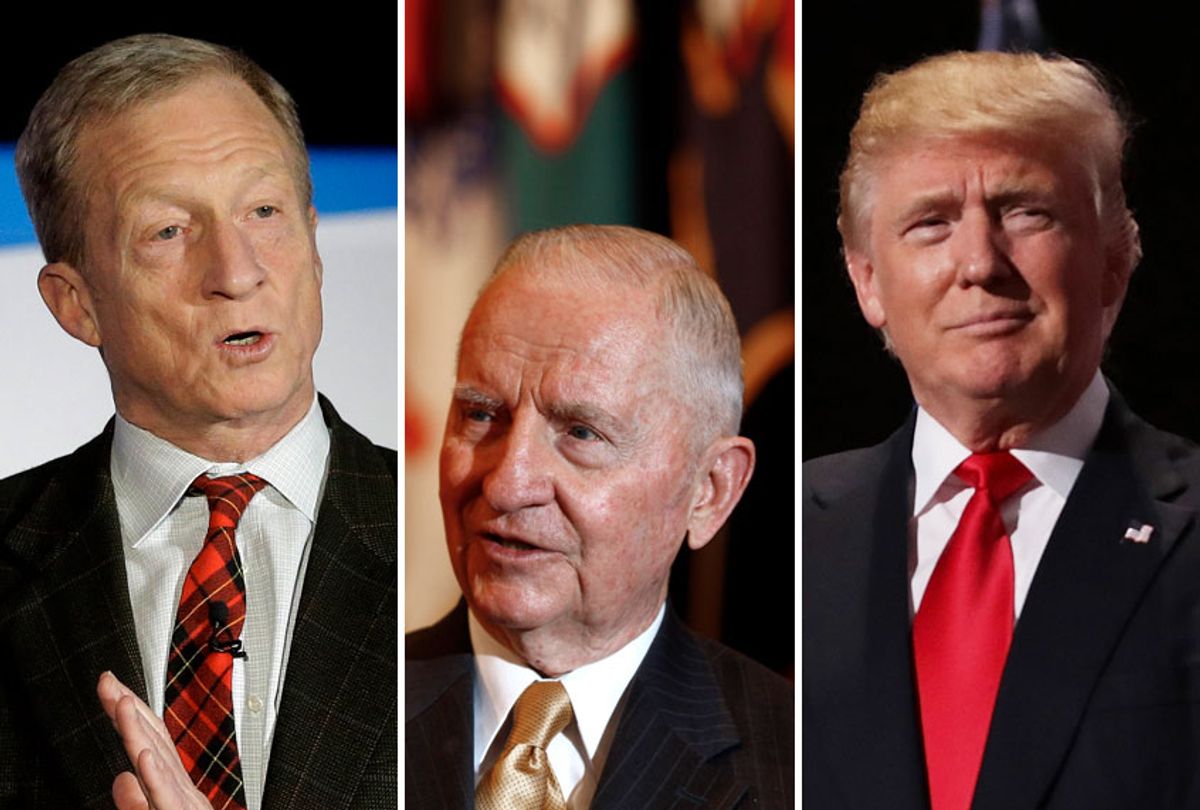

Computer entrepreneur Ross Perot passed away this week, reminding us of the 1992 prototype of the campaign that brought Trump to the White House 20 years later. Perot ran the most successful third-party campaign in almost a century with an eccentric mix of protectionist philosophy, military fetishism and an obsession with the budget deficit. He had a gift for media and he created the Reform Party out of whole cloth by simply going on Larry King's CNN show and saying that if people got him on the ballot in 50 states he'd run for president. They got it done.

His campaign was a circus, however. He withdrew from the race at one point, saying that Bill Clinton had "revitalized" the Democratic Party, only to rejoin it later, after complaining that the Bush family had tried to sabotage his daughter's wedding. He was a paranoid conspiracy theorist who got the FBI to investigate whether the Bushes had tapped his phones — and said in a national debate that the Vietnamese had hired Black Panthers to have him assassinated.

Nonetheless, he got 20% of the vote from people who were entranced by the idea that a billionaire "populist" was going to "get under the hood and fix it" (Perot's prequel to "Drain the swamp.") He ran again in 1996 and won 8.4% of the vote, which was the third-highest third-party vote of the last century. (George Wallace got 13.5% in 1968.)

Donald Trump's first run at the White House came as a Reform Party candidate in 2000, and you can see why he might have thought it was a good fit. He dropped out before he really got started (it was mostly a publicity stunt) but he did come away with the insight that it wouldn't be worth doing in the future as a third-party candidate.

As with Perot, being a successful businessman was the basis of Trump's sales pitch, despite the fact that it isn't true. As we now understand (or certainly should), Trump is actually a man who inherited great wealth and spent his life promoting a phony image as a self-made success even as he lost mountains of money in bad business deals. It's been a disaster. His scandal-ridden, corrupt administration and his personal incompetence and cruelty are epic in scope. Yet it hasn't deterred his base, the roughly 40% of the electorate who seem to believe that any rich guy who "tells it like it is" is some kind of genius.

That also hasn't deterred more billionaire outsiders from seeing the path of Perot and Trump as a signal that the country is yearning for their genius leadership as well. Billionaire and former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, has been flirting with a presidential campaign for years. He decided to sit this one out (so far), disappointing all the NeverTrumpers who were yearning for a Republican to win the Democratic nomination.

Bloomberg at least was a big-city mayor, which gives him years more experience than former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, who is (perhaps) running for president as an independent on the assumption that running a global chain of coffee bars is the perfect training to run the most powerful nation on earth. At this point there's no indication that voters find Schultz particularly inspiring, and he's recently said he's taking a hiatus from campaigning for health reasons. I'm not sure anyone remembered he was campaigning in the first place.

This week has brought us the latest in rich-man vanity politics with the news that hedge fund billionaire Tom Steyer is planning to throw his hat into the ring, pledging to spend $100 million on his campaign. Steyer has funded some good political projects around climate change and voter engagement, as well as pushing for Trump's impeachment in TV ads for well over a year, so he isn't a total novice. In fact, he's selling himself as an activist more than a businessman. But like all the rest of these rich guys his main pitch is, "Nobody owns me. I'm not afraid to speak my mind. I'm not beholden to them. I'm not beholden to the establishment."

Trump said that too, and he's right. Nobody can tell him anything, and we can see that that's a huge problem. Our experience with him proves that it makes no difference whether the billionaires own the politician or the politician is a billionaire. Either way, we get self-serving rich egomaniacs who are convinced they are all stable geniuses calling the shots. History shows they aren't very good at it.

Shares