Everybody wins all of the time, or at least that’s what social media in our current culture wants you to think. We all have that one high school friend with the perfect Instagram that they masterfully curate for us to enjoy. And we do enjoy how they only eat the most delicious meals off of perfectly staged plates next to artfully foamed lattes, or when they perfectly zip line through scenic views on their monthly trips to the islands where they are celebrated by the locals, as if they are in position to become their new leader. You never see them have a bad day, share bad news or connect with anything regular.

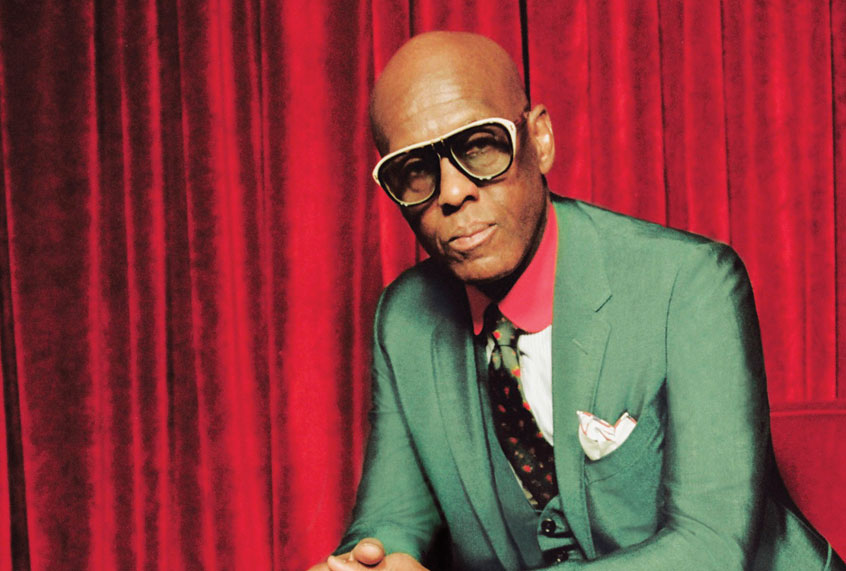

That’s a major problem with today’s society. We are so used to seeing wins — or what looks like winning — that we tend to forgot the hard work that success really takes or that hardships will happen. No one knows this more than Harlem legend and fashion icon Dapper Dan. Most people know Dapper Dan from his legendary store on 125th Street in Harlem where he pioneered high-end streetwear in the 1980s, remaking classic luxury-brand logos into his own innovative designs for a host of celebrities including Mike Tyson, LL Cool J, Salt-N-Peppa and Jay-Z, to name few. If social media was out at that time, he probably would’ve averaged 5,000 likes per picture, just like your friend from high school. But what’s on the other side of those likes? What did Dapper Dan have to overcome?

What most people don’t know is that he bought the boutique with money he earned from being a professional gambler. People know about the celebs wearing his fashions, but they don’t know that those celebs were copying street trends from famous gangsters. People also don’t know that Dapper Dan’s shop closed because of raids ordered by the major fashion houses, that he was shot in the neck in front of his store, and that he went broke after experiencing all of that only success— only to rebuild his company from the ground up and orchestrate a historic partnership with Gucci.

I had the chance to address many parts of Dapper Dan’s life, along with the importance of hard work, the pain it generates, and the power sharing those experiences when I sat down with him in Salon’s studio to talk about his new memoir, “Dapper Dan: Made In Harlem.”

Watch my “Salon Talks” interview with Dapper Dan here, or read our conversation below.

We see people cling to culture all the time, but every once in a while, we get a person who pushes culture forward and creates something that’s going to outlast everything. You’re one of those cultural icons here, the great Mr. Dapper Dan. What does culture mean to you?

Culture is something that I had to study deeply to make sense out of. Culture’s what took me to Africa. Culture is what made me create fashion. Culture is who we are, the sum total of us. It’s the bottom of us. It’s what we had to rebuild here in America. Culture is where we started off and where we are now. When I look at hip hop music, when I look at the music and our contribution to America, I see a new culture, a culture that basically didn’t even start, and didn’t free itself up in any sense until Emancipation Proclamation. Our culture’s probably the youngest culture that you might find in the Americas.

Many people think that style comes from celebrities, but I always felt like the trends come from the street. It’s always like a celebrity person that has some connection to some street guy, and he walks into the studio or he’s behind set at the movie, and they’re like, “Oh, what are you wearing? Where’d you get that jacket from?” Or, “What are those sneakers?” Then it becomes a thing. Do you find that to be true in your experience?

In my experience, style is dictated by strength, strength in the community. It’s like certain guys have, they could be like a real good dancer, real good hustler, but somebody who generates excitement. I’ve always played behind that. You can have excitement without style, but you can’t have style without excitement. Style has to generate excitement. That’s the key to everything I do, is to generate excitement around what I create. Then, we build off that. We go get exciting people and use that as a package. But style is excitement.

Tell us about the Harlem that you come from. Before the public housing, before the gentrification, and before this idea of Harlem that’s put in the mainstream. Give us a glimpse of that Harlem where you grew up.

I like talking about that. I always look at Harlem like I look at the Harlem River: It’s always there, but it’s always moving. You can never step in the same Harlem River in the same time. I’m so fortunate to have navigated that river so many times. But the Harlem I grew up in is the Harlem I like to talk about. I’m the first generation of the Great Migration, and I saw what we was like before a lot of other things happened. I was born in the Harlem of, what I call the Holy Ghost Harlem, when we all went to church.

Everybody went to church.

Eleven o’clock was considered America’s most segregated hour, because you see all the black people in the ’50s, we would empty out the houses. Everybody would be going to one of the churches. I grew up in a Harlem when Harlem was truly a village, when everybody looked out for everybody, and you were scorned and ostracized if you did something wrong in the community. That’s the Harlem I grew up in. I watched that Harlem change. I watch the riots change Harlem three times. I grew up with Italians, Irish, Jewish people, and a lot of us, and a lot of Puerto Ricans. That’s the Harlem that I know.

One thing that I didn’t know that I learned from your book was the neighborhoods were kind of sectioned off. Your neighborhood in Harlem was sort of based on where those family members and friends from the same part of South Carolina came from.

Yes, yes.

So if you were living in this part of South Carolina, you might live on this block or this section.

That’s right. I think that had a lot to do with the sense of community. Because somebody would be up here, they’d say, “We got place for Juneboy, tell him to come on up.” That’s how a neighborhood was built. I found out that’s even true today, like in the Washington Heights, with my Dominican friends, it’s the same thing. They all come from a particular town. That was big in Harlem. We had the South Carolina boys, and North Carolina neighborhoods, and a lot of people from, let’s see, probably be Georgia. Those are the three communities I remember a lot.

There’s a lot of pictures of you floating around the world and on the internet. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen you slipping in one picture. What does being fly mean to you?

Liberation. Because I couldn’t get fly when I was young. I grew up with holes in my shoes, and I said, “If I ever get the opportunity, I ain’t never come out of these fly clothes.” If I’m slipping, help me up, because I got to be fly.

What’s an off day for Dapper Dan? Like a sweatsuit?

If I’m running out to store real quick and it’s raining, yeah. [Laughs.]

Your dad was fly in his own right, too. You write about that in the book. One of the stories that I thought was liberating and powerful is when you talk about how you stopped him from signing a bad contract.

Yeah, I was 13, I was going to get my first suit, and we went into Ripley’s department store, and we was going to pay for the time. I just learned a mathematical equation on what it would look like, time times rates, and what the interest would be. I said, “Dad, don’t buy it.” We’re coming down the stairs, coming out the store, and my father stopped me on the stairs, and he looked into my face. I saw tears welling up in his eyes. He said, “Boy, don’t you know you could read?” He said, “Boy, you could read.” It all came back to me, because my father only went to the third grade. Father was born in 1898, 33 years after Emancipation Proclamation. He left the South at 12 years old. He had to teach himself to read. When he saw me read and break that contract down, that was like I graduated from college, man. He said, “Boy, you could read.”

Was that the point when you realized the importance of reading?

That’s when I realized that whenever I get in a situation, I can read my way out of it. Nothing in my life that I have achieved will supersede the fact that I learned how to read, and I use reading as a vehicle to get me out of places and to teach me and allow me to learn the things that I need to learn, no matter what I did in life. Reading is liberation for me.

What are some of the key books that stuck out when you were younger?

The first one was “Man’s Higher Consciousness,” by Professor Hilton Hotema. Always had questions about God, creation and things like that, and I even wrote poetry on it. The second most important novel was “The Secret of Regeneration,” also by Professor Hilton Hotema. But there have been others that would motivate me. It’d probably be Malcolm X and his book [with] his speech to the grassroots.

In his speech to the grassroots, he says, “If you want to understand the flower, study the seed.” I use that as a means to teach myself everything. Not only did I read and I liked reading, but that showed me how to read with directions. When you want to know something, go looking for the information. Go looking at where that information come from, the source of that information.

Other than that, Krishnamurti. The most important book I read by him was “Freedom from the Known.” Krishnamurti talks about [how] we have to first free ourselves up from what we already know, so that we can prepare ourselves to teach ourselves.

You almost became a journalist, or you were headed for that path. What would Dapper Dan the journalist look like?

Oh man, I wanted to know why. Journalism has always been a why thing to me. I remember when I got the opportunity to go to college and I took Philosophy 101. I wanted to know, where does all this start from? In Philosophy 101, we studied Thales of Miletus, considered the father of philosophy. He said, “The first question of all learning is why.” I always wanted to know why, so I would read all kinds of books.

But, on top of that, when I was writing for the student newspaper, 40 Acres and a Mule, we used to have black scholars come in, Dr. Ben-Jochannan and Dr. Henry Clarke. One day Dr. Henry Clarke was in there, and one of the students on the editorial board asked Dr. Henry Clarke, he says, “If we, as black people, are the first chosen people on the planet, we are the first ones that God created, why are we going through what we’re going through today?” Dr. Henry Clarke answer was, “That was because of a transgression that we made before Europeans came into our lives.” That’s what really sent me on a journey, from that then there, from my instruction there. Everything I did had to be focused on why. If something happens to you, everybody should want to know why it happened.

So I went to Africa, I went on a seven-trip tour when I was in prep school. We didn’t do hotels, we did live-ins. I was looking for the answer to that. Several times I thought I came across the answer.

This is one of the parts of your journey that I found more fascinating. This whole idea of the safe thing for you to do would be to go to the Columbia journalism program over the summer, but the right thing for you to do would be to take the Africa trip. People tried to stop y’all from going.

Yeah, oh yeah. United States government, when they found out that we were young rebels, they didn’t know we was radicals, because there was nobody like us, young people like us. So Pan America airlines has donated the tickets for us to go, and the state department told them, “Look, don’t do it. These are young radicals.”

Why do you think they didn’t want y’all to go? What do you think they were trying to stop you guys from seeing?

Because they saw the itinerary. We was going to be staying at revolutionary schools in Africa. We stayed at Kurasini International Revolutionary School, where they was training Africans from South Africa to fight in South Africa, and to fight in Angola. When they saw our itinerary, they was upset, so they canceled. Then we had a black philanthropist put up the money at the last minute so that we can go. Then when we land in Ghana, at the first leg of the trip, our passports disappeared and then reappeared at the embassy in Ghana.

So when you guys were flying they didn’t allow you to travel with your passports?

No, we had our passports, we all kept them together, but when we got to Ghana, the passports disappeared. Then they turned up at the state department. We had to go to the United Sates embassy to pick them up. Then we learned later on that the entire trip, we was accompanied by a CIA agent. It was in the ’60s, so that was the COINTEL program, so they didn’t know what to expect out of us.

Did going to Africa have an influence on the way you dress? Did your fly evolve and change once you got back to the states?

Yeah, when I came back from the states, I was completely engrossed in African culture. I knew more about myself and more about Africa. But it was the second trip that really made a big difference, because I had my own money, I was traveling on my own. That’s when I went to see Muhammad Ali.

That’s when you went to go see Muhammad Ali fight George Foreman, the Rumble in the Jungle.

Yes, the Rumble in the Jungle. On that trip, I was super fly then. First, when I was in prep school, I was struggling. But now, skills had kicked in.

Were you Dancing Dan back then, or you were Dapper Dan?

I was Dancing Dan. No, Gambling Dan. That was Gambling Dan then. When I was Gamblin Dan, I made a lot of money, so that’s when I went to see the fight. I said, “Wow, I get a chance to go back to Africa.” Stopped over in Zaire. That was in Zaire. Then I stopped over from Lagos, Nigeria. Because the first time I went on the trip, I couldn’t get off in Lagos, Nigeria, because they would fight, because it was the Biafran War. The tribal war between the Biafran and the Igbo and the Hausa.

So I end up in Liberia, and I had a tailor there. Guy was selling artifacts. I went in there and said, “Wow, I like them artifacts. I want to buy some artifacts.” He said, “I like what you wearing.” I said, “Really?” I ran up in the hotel. I said, “You want to trade?” He said, “Yeah.” I ran up in the hotel and got everything. I said, “I don’t need to take these American clothes back.” I put all my clothes back down to the marketplace, traded them for artifacts. I said, “How about we trade some and you make me clothes?” This is the beginning of what you hear me say is Blackenize or Africanize European fashion. So I had him make me clothes, African fabrication, with styles that we like in America. That was set down in my brain, in my mindset, for later on for what I do. I came back completely Africanized.

When you came back, and some time passed, and you eventually opened a store, were you thinking that the store was going to completely be a shop for custom pieces?

No.

Or you thought you wanted to just sell furs?

No, I thought that I’d be able to buy from luxury businesses, people who made luxury fabric, the big guys, distributors. So, high end. When I found out they wouldn’t sell me high end, I remember that, I said, “Wow, I had clothes made in Africa. Maybe I should get me some African tailors and make these clothes and show them I can make clothes better than even the ones who wouldn’t sell to me.” That’s when I embarked on that.

I think the beauty of what you have done is that you created a reality, a system that was important, extremely important, without the outside acceptance.

Yes.

Who cares what’s happening downtown? Who cares what’s happening over here, over there? This is about our section, our people and what we want.

Right, I felt like I’ve always been looking for us, and I found us in us. I said, “I’m going to cater to that. I’m going to make things the way we want to.” Because that’s the big difference in buying from wholesalers and creating yourself. When you create for yourself, you know exactly how you want to look and exactly how you want to feel. It came on so naturally, and it felt so good, man, it was a happy place to be.

During that time, do you think you can identify your top three flyest customers, like the ones who pushed you the most?

Oh yeah, Jack Jackson. Jack Jackson was the last person to completely control the drug trade, the last black guy to completely control the drug game in Harlem. So, if I win him, I win Harlem. You got to get the kingpin, and Jack Jackson was the kingpin.

He was ranking number one?

Yeah, he was ranked number one.

Alpo copied Jack. Alpo got his swag from copying Jack. Alpo used to come to the store, and he couldn’t even come in when Jack was there. After Jack leave, he actually said, “Yo, what did Jack get?” I built around that. You build around images. Like I told you earlier, it has to be an element of excitement, and Jack was that. He had the latest cars, he had the flyest jewelry, he had the most money, and everybody knew it. So it was Jack that was the vehicle I used to generate the excitement and put my clothes on.

What about the other top three customers that pushed you the most?

It would have to be a rapper then, because it shifted. Which rapper would that be? That had the most outfits? It would be like a three-way race between Jam Master Jay and Run D.M.C., Eric B and Rakim, and L.L. [Cool J]. Those three, they pushed the envelope for me.

When it started getting popular, that’s when you got some attention from the store, but it wasn’t the type of attention that was good for business.

It was underground. It was off the radar.

The big labels started hating. And you write about the raids and your meeting with Supreme Court Justice Sotomayor.

That came as a result of Mike Tyson having a fight in the store. It generated so much attention in the media, that everybody was saying, “Well, what the hell is a Dapper Dan?” Then they started paying attention, and rap music was taking off then. So that caused some to zero in on me and they started getting cease and desist orders from the courts, thinking that they could just come in and take anything that has their logo on it, or any machine that was used to create that logo. So they kept raiding. One day, Sotomayor, at the time, was the lead attorney for Fendi, and she led the raid that finally was the death blow.

One of the things I enjoyed reading in the book was the whole way of how you built this empire, and you had hardships, like most people in business do, then you fought back. Now, you’re back and you’re better than ever. You’re having a new fight with people — I’m not going to say boycotting, really, I’m going to say pretending to boycott Gucci. They’re pretending to boycott Gucci. But something that you said to me, but when we were talking earlier, with this whole idea of, why boycott without having any real goals or values? Why boycott without looking for a win? Could you speak to that win?

Yeah, that’s the thing that’s troubling today, but I kind of understand it. The younger advocates today don’t understand what transpired during my generation. Every boycott that I ever read about, or every bad boycott I’ve ever seen in my presence of growing up, has always had an end goal. This is the first boycott that does not have an end goal that’s going to enrich us in some way or another. Boycotts is about getting in the door, sitting at the counter, being able to go where we want, be where you want, get an education, to vote. All had an end goal. This is the first boycott that has no end goal that’s going to enrich us in any way.

How do we translate that message? How do we get that message out to people? I don’t think that they are not used to winning.

Yeah, exactly. I don’t think they have seen enough results about what boycotts can do, and what activism can really accomplish. I really think that I have to have a voice, and I need more voices, to explain to them where we need to go with this. So, flex your muscles, but don’t punch them and then walk away. We get nothing from that. So, we need messengers out here to let them know that we’ve got to accomplish something.

The message should be, like it always has been, “Let’s get inside and change it from inside.” That don’t mean we neglect the outside. We can always still try to create business, but we cannot create business and compete against multi-national corporations and think we’re going to do that tomorrow. You’re talking about a long endeavor, man. So, we should do both. We should be inside, getting the knowledge that it takes to run these multi-national corporations, while at the same time, other people can engage in trying to have start-up businesses. When you’re talking multi-national corporations, you’re talking power there. You know? On one hand, it’s a great thing for us, because it’s making us think about these things, so I’m happy about that.