At the end of the day, we are not just victims, we’re fighters.

—Melissa Mays, interview with author, February 17, 2016

In July 2014, three months after the switch to the Flint River, Melissa Mays began to notice changes in her water. It would turn yellow sporadically, sending her three sons charging through the house “running and screaming” to relay the news to their mother.1 Filling up the family’s porcelain bathtub revealed a more consistent bluish tinge. The water also began to smell peculiar: depending on the day, it would reek of rotten eggs, dirt, or bleach.

Mays remembers thinking these developments were “weird,” but her initial impulse was to brush them off. The city, she recalled, had warned residents at the time of the switch that river water was different from lake water, and that the water would take time to “level out.” Although Mays later came to see official explanations like these as “excuses,” at the time they seemed like logical and well-intentioned efforts on the part of knowledgeable authorities to inform and reassure residents. She assumed the government agencies entrusted with public health had done their due diligence and would alert the public if there was any cause for concern.

What began as mild uneasiness about the water’s fluctuations developed into real alarm, however, when Mays and her family were beset by a mysterious series of ailments. Upon contact with the water, she told me, their skin would break out in rashes—“bumpy and lumpy” rashes that felt like a “chemical burn” and were unresponsive to eczema cream. The water seemed to be affecting the family’s hair, too. Mays watched her sons’ naturally “silky” hair become “rough and wiry.” Her own hair started falling out in the shower. Even the family cat’s fur, she said, would slough off whenever someone would pet it.

In September, Mays instructed her family to stop drinking the water. But this was not the end of their exposure (they continued to use the water for cooking and showering) or the end of their perplexing health issues. The boys started complaining of muscle and bone pain: eleven-year-old Cole told his mom that his bones “burn from the inside out.” Soon thereafter, Mays said, she started suffering from similar pains herself. When Cole fell off his bicycle and thrust his hand out to absorb the impact, his wrist buckled in two places, leading his doctor to surmise that his bones were unusually brittle. Mays’s oldest son, seventeen-year-old Caleb, began to develop holes in the smooth sides of his teeth, a sign that rather than decaying in the usual fashion they were crumbling from the inside out. Furthermore, all three boys became lethargic, “tired all the time.” Their sluggishness was mental as well as physical, manifesting itself in “brain fogs” that led to difficulties at school. Twelve-year-old Christian, a consistently straight-“A” student, got his first “C,” and Caleb and Cole, who were forgetting skills already learned and finding it hard to remember new information, had to be assigned tutors.

Unbeknownst to Mays at the time, her family’s ordeal was not unique. Across town, LeeAnne Walters and her family, too, began breaking out in rashes in the summer of 2014. Three-year-old Gavin would emerge from the bath with a visible water line, below which he was so red and scaly that when Walters tried to apply moisturizing ointment, “he would scream and cry about how bad his skin burned.” Walters had to start giving him Benadryl before bath time as a preemptive measure.

At first, the doctors said Gavin’s rashes were contact dermatitis caused by an allergy of some kind. Then their diagnosis shifted to eczema and they instructed Walters to apply cortisone to the affected area. When the rest of the family began to develop rashes of their own, however, the diagnosis changed yet again: this time Walters was told that everyone had scabies. The treatment was another prescription cream, a pesticide meant to kill the tiny mites thought to be the source of the problem.

In the meantime, further evidence emerged that the water, not mites, was the real culprit. At a party celebrating eighteen-year-old Kaylie’s high school graduation, a group of invited guests broke out in the same telltale rash after swimming in the family pool. With this incident fresh in her mind, Walters balked when doctors returned a third diagnosis of scabies the next time she took Gavin in, insisting on further testing by a dermatologist outside city limits. A skin sample showed no evidence of any organism that would have accounted for the rashes.

Like the Mays family, the Walters family also experienced hair problems. Walters recounts rushing up the stairs in response to Kaylie’s screams to find her “standing in the shower, staring at a clump of long brown hair that had fallen from her head.” Kaylie was not the only one: the other members of the family were losing hair, too. At one point, Walters lost all of her eyelashes.

Problems with skin and hair were bad enough, but once again they were merely preludes to more serious conditions. In November, fourteen-year-old J. D. began to experience “terrible pains, dizziness, nausea.” He had “a hard time walking up steps” and grew so ill that he missed an entire month of school between Thanksgiving and Christmas. At one point during the barrage of inconclusive tests that followed, doctors speculated that he had some form of cancer.

Just as J. D. was getting over his symptoms, the water in the Walters household turned brown. Walters’s initial reaction was disbelief: all water coming into the house was passing through the whole house filter she and her husband had installed when they purchased and renovated the home in 2011. Even after swapping out filter cartridges, though, the water continued to arrive at the kitchen sink the same disconcerting rusty shade. Deterioration of pipes within the house could be ruled out, given that they were only a few years old. There could only be one conclusion: the water coming in from the city was so contaminated that even a filter was no match for it. In December 2014, the family began to use bottled water.

While the whole Walters family had suffered in one way or another up to that point, Gavin, who was already immunocompromised and who tested positive for elevated blood lead, was ultimately impacted worst of all. Despite Walters’s efforts to prevent his coming into contact with the water, his health continued to deteriorate. He developed anemia and speech issues, having difficulty pronouncing words he had already mastered. Most alarming of all, he stopped growing. As his fraternal twin Garrett continued to gain height and weight, Gavin plateaued. Two years after the switch to the river, more than two inches and almost thirty pounds separated them.

Before their lives were turned upside down by contaminated water, neither Melissa Mays nor LeeAnne Walters considered herself a political activist, or even politically inclined—Mays had been to one political march in her life, Walters had dabbled in advocacy around stillbirth awareness. But out of the conjuncture of foul water, poor health, and the responsibility they felt as mothers to protect their families, they would develop into two of Flint’s most prominent “water warriors.” In the process, they would come to understand their personal experiences of contamination as products of larger sociopolitical dynamics that converged to cause the crisis, and their determination to protect themselves and their families would evolve into a broader commitment to the people of Flint and a newfound sense of political agency.

Many of Flint’s water warriors followed a similar path to political action, driven not by prior political commitments but by the personal impact of contaminated water. For these residents, the first manifestations of the water crisis were often tangible harms to bodies, minds, and property: a stubborn rash, a child afraid to take a bath, a water heater corroded before its time and in need of replacement. These kinds of harms comprised the human face of the crisis, and they generated much of the emotion, energy, and resolve that fueled the burgeoning water movement in Flint. For personal troubles to be translated into collective political action, however, residents had to develop the belief that there were political remedies to their problems. They had to learn to direct their anger toward specific people, institutions, and policies. And they had to see their own struggles as intertwined with those of their neighbors and demanding of a common solution.

Residents also had to develop a belief in themselves as political actors, people who were capable of understanding what was going on with the water, judging what needed to be done, and mobilizing to do it. The treatment they received at the hands of officials was not, prima facie, conducive to fostering such self-confidence: with eye rolls and snide remarks, officials implied that residents were overreacting to changes in the water, jumping to conclusions about the causality of health symptoms, and unable (or unwilling) to assess the situation rationally. But far from causing residents like Mays and Walters to doubt themselves and withdraw back into the private realm, the experience of being dismissed caused them to grow even more certain of their views and assertive in voicing them. It also got them thinking about politics: the problem in Flint was not just that government failed in its protective function—“they” didn’t keep us safe—but that it failed in its representative function—“they” didn’t listen to us and act on our concerns. In light of these failures, residents vowed to take charge of their own health, carry out their own research on the water, and force unresponsive decision makers to act.

Into this formative moment stepped the politically seasoned activists of the Flint Democracy Defense League. They introduced into the discourse of the water movement concepts and demands drawn from the pro-democracy movement, infusing immediate concerns about water quality with a farther-reaching political consciousness and strategic agenda. Thanks in large part to their influence, rusty water in the bathtub and blotches on the skin came to symbolize more than just a water crisis: they were the stigmata of democracy denied. Even newly politicized residents came to embrace the idea that the crisis would not be over, nor justice for Flint realized, until democracy was restored.

What I will call the water “movement” in Flint consisted, then, of the potent fusion of activists who came to water through democracy and residents-turned-activists who came to democracy through water. That fusion of collective action has its roots in residents’ everyday experiences of contamination and ill health, in the disrespect they suffered in their interactions with political officials, and in their developing sense of being united in the same predicament—and the same struggle.

# # #

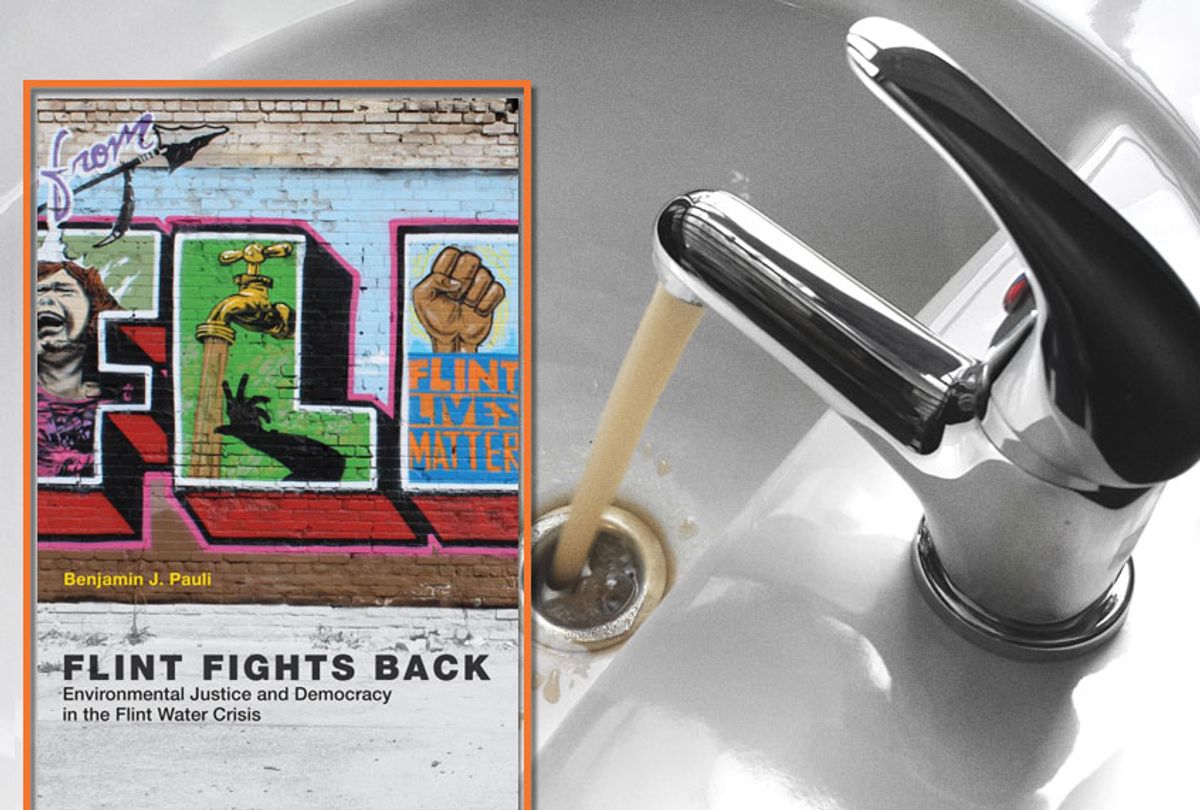

Adapted from "Flint Fights Back: Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis," by Benjamin J. Pauli. Copyright 2019, The MIT PRESS.

Shares