Last week, before Trump’s buffoonish cave on his attempt to hijack the census, Greg Sargent wrote about Attorney General William Barr’s emerging role as Trump’s enabler in undermining the rule of law — first in the census case, then in the challenge to the Affordable Care Act.

The connection between the two is straightforward, according to University of Michigan law professor Nicholas Bagley. “In both, Barr directed his lawyers to make bad-faith arguments, just because Trump said so,” Bagley told Sargent. “That’s a blow to the integrity of the Justice Department and a threat to the rule of law.”

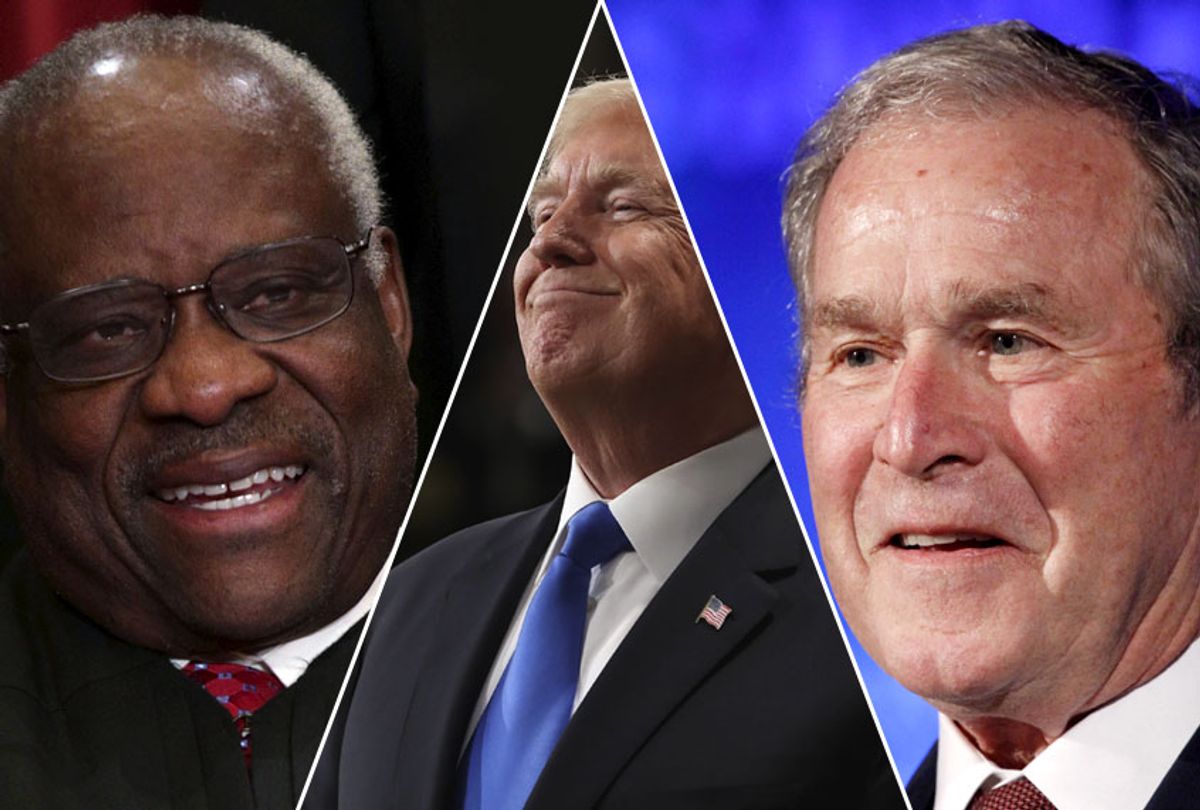

As with much else about the Trump administration, the bad-faith arguments are nothing new; Republicans have long been the party of bad faith. The most notorious Supreme Court decisions of recent years — from Bush v. Gore through Shelby County, Citizens United and more — can all be attributed to bad faith arguments and actions by the justices involved.

Then there’s the myth of originalism and the long history of lying during Supreme Court confirmations, with Brett Kavanaugh's example only the most recent. If the judicial doctrine known as "originalism" was rhetorically advanced by conservatives to supposedly counter “activist” judges, in practice it accomplishes exactly the opposite, as Richard Posner’s critique of Antonin Scalia makes clear.

What’s arguably new is the stark nakedness with which these ideas are advanced — revealing the bad faith as a feature, not a bug — combined with the reckless three-ring-circus atmosphere in which they’re being tossed out. (That was what ultimately doomed the census question, not its substance.) That bad faith has long been evident in a wide range of forms, as Bagley told me by email.

Republican arguments against the [Affordable Care Act] have been permeated with bad faith from the get-go. Some of that bad faith involves outright lies: Think death panels. Some of it reflects a willful or deliberate ignorance of the tradeoffs that health-care policymaking entails. (You can't cover everyone, cut spending and eliminate insurance regulations at the same time.) And some of it is pure gaslighting, like the claims that Republicans are dedicated to protecting people with pre-existing conditions (they're not) and that they have a replacement plan to provide wonderful health coverage to everyone (they don't).

There’s one more he left out: GOP complaints about Democrats “ramming [the ACA] through Congress” via reconciliation without any Republican votes, as if they’d made no effort to craft a bipartisan bill. As Salon noted at the time:

Senate Democrats have accepted at least 161 Republican amendments to their health care reform legislation, they've incorporated core GOP planks, and they've scuttled an aspect of the plan most popular with its base, the public option, because of opposition by Republicans as well as red state Democrats.

This is a repeated pattern. It doesn’t seem to matter how much Democrats compromise on the details. Whatever they put forward, Republicans will counter with sweeping rhetorical bad-faith attacks as surely as night follows day, for reasons that will become apparent below — an asymmetry between the two party’s strengths. First, let’s establish some historical reality about where all this bad faith is coming from.

Bad faith, Southern-style

For that, I turned to Angie Maxwell, co-author of “The Long Southern Strategy,” whom I recently interviewed here. Her account about how the GOP had transformed Southern politics — and transformed itself in the process — was a tale drenched in bad faith, as I read it: All the NeverTrumpers who’ve now abandoned their party in horror had been cultivating Trump’s base for decades, whether they realized it or not, using manipulated public resentment for often-unrelated purposes. Trump is their comeuppance, but his bad-faith appeals are nothing new.

“If you think historically about what organization has operated in bad faith more than any other, you would have to say the Confederacy,” Maxwell said, pointing to “the idea that all of these poor Southern whites" — who did not themselves own slaves — "would take up the cause of the Confederacy for something that will not benefit them economically at all, the preservation of slavery.

“Christian nationalism, particularly the way in which they couch it in terms of ‘states' rights,’ was itself a bad faith argument. And it got worse years after the Civil War when arguments about why Reconstruction was wrong were made in bad faith — reasons that justified lynchings, all those arguments were made in bad faith. The Lost Cause is at its core a bad-faith argument.”

All that history of bad faith belonged to Southern Democrats at the time, of course. But Republicans eagerly took it over for themselves, as Maxwell's book describes. As she notes, it wasn't politically necessary to focus on bad faith:

If you decide as a party to try to go capture those voters, there are aspects of Southern white identity that are not bad faith that you could have tried to tap into: there’s the family, rural culture, there's even good-faith ways to talk about religious values. But a whole other chunk of white Southern identity is really built on bad-faith arguments about white supremacy, patriarchy and Christian nationalism. So if you're trying to win those voters, bad-faith arguments are kind of your bread and butter.

The story begins in earnest with Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign, when he won five states in the Deep South. That election provides a telling glimpse at how bad faith generalizes, which we’ll return to below. Four years later, the problem Richard Nixon and his advisers faced in the South, as Maxwell explains it, was that since Alabama Gov. George Wallace, running as a third-party candidate, was going to get the hardline white supremacists, "How do we get everybody else?”

Their answer, she says, was “law and order," a "coded language" or bad-faith argument used to lure racist voters without quite saying so. Some voters were legitimately attracted to that argument, she noted, but plenty of others understood exactly what that meant. When Republicans denied any racist intention — “Well, I’m just talking about law and order" — they were making a bad-faith argument.

The same applied to the next stage of what Maxwell calls "The Long Southern Strategy," the attack on feminism that depicted it as a form of tyranny:

Feminism is choice. That's what it is. Well, Phyllis Schlafly creates a false equivalency of anti-feminism, and it's a bad-faith argument. Because it cast feminism as the demand that you be a certain way, but ... the opposite of feminism in that case is sexism, not anti-feminism. So, telling those women that the government is going to force them to put their children in day care, it was a bad faith argument, that manipulated a lot of people into going, "The feminists reject who I am. They want to make me be somebody I'm not." And it worked. That is a bad faith argument by its very nature.

There were legitimate arguments to be had about how to achieve "opportunity, equality and choice" for women, Maxwell adds. Republicans were eager to avoid framing the argument as, "'Well, you should have this equality, or you shouldn't.’ You can't really say, 'We don't support that.' So you have to wrap it in some kind of bad faith camouflage. Like you say you're worried about voter fraud, even though there's no evidence of voter fraud. So what you're really doing is just trying to suppress the vote."

Bad faith in the courts: A prelude

Those are some highlights of how we’ve gotten here, but none of that can explain what's happening in the courts. Indeed, for a long time the courts seemed to pose a kind of limitation on bad faith. As Maxwell put it, “When you get court and you try to justify your argument, it looks contrived. Because false equivalencies and bad faith arguments rarely stand up to logic and reasoning.”

But the census case itself is proof of how determined Republicans are to push on this front — and how close they’ve come to success. As Adam Serwer noted before Trump threw in the towel, “Again, this is not just Trump. The Republican establishment is urging the president to do everything he can to reestablish the foundations of white man’s government.”

To understand what’s happening in the courts, I think in terms of layers: There’s an asymmetry in our politics that shapes an asymmetry in our courts. As mentioned above, Goldwater’s capture of five Deep South states in 1964 provides a peek at how bad faith spreads in this environment.

Public opinion pioneers Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril fielded a study that year, with results published three years later in “The Political Beliefs of Americans.” Their most striking discovery was a profound division: On the symbolic and ideological level, Americans lean more to the right, favoring "free markets" and "small government." But they lean even more strongly to the left when it comes to operational details — support for specific spending programs. In fact, they found that 23% of all Americans were both ideologically conservative and operationally liberal, a condition they called “almost schizoid.”

What’s usually overlooked, however, is that this figure doubles to 46% within the Deep South states that Goldwater won. There are both good-faith and bad-faith ways of dealing with these contrasting views. A good-faith way would be to say, “I’m in favor of the free market and limited government, but when the market fails government action is absolutely essential.” A bad-faith way would be to say: “Welfare only helps the undeserving — and by the way: Keep the government's hands off my Medicare!” Guess which one you hear most often? It’s no surprise the South was a Petri dish for cultivating bad-faith narratives.

Republicans naturally focus on the ideological and symbolic side, while Democrats focus on operational specifics, which is a key component of Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins' book "Asymmetric Politics" (Salon review here.) The lack of symmetry between Democrats and Republicans is also reflected in clashes over constitutional norms, producing what Joseph Fishkin and David Pozen describe as “Asymmetric Constitutional Hardball” (Salon story here.)

“Since at least the mid-1990s, Republican officeholders have been more likely than their Democratic counterparts to push the constitutional envelope, straining unwritten norms of governance or disrupting established constitutional understandings,” they wrote. A followup paper, “Constitutional Hardball vs. Beanball,” by Jed Shugerman (Salon story here), introduced the element of bad faith into the mix.

“You have another category of hardball," Shugerman told me: "Bad-faith hardball,” in contrast to "transparent hardball”:

The confirmation of Justice Neil Gorsuch was an example of “good-faith hardball," Shugerman said. Republicans "decided to get rid of the [Senate] filibuster because they want to get him through, but everyone sees it happening, and it's not being constructed by a lie." But Mitch McConnell's Senate blockade of Merrick Garland, Barack Obama's final Supreme Court nominee, was “bad-faith hardball," and the battle over the Kavanaugh confirmation was "bad-faith beanball.”

So what seems a relatively simple story of bad faith as an important thread within the larger story of asymmetrical politics begins to get far more complicated. I reached out to David Pozen, one of the authors of "Asymmetric Constitutional Hardball," to ask whether the doctrine of constitutional "originalism" was in essence a bad-faith rhetorical framework, meant to delegitimize "judicial activism" by liberals or progressives while justifying it for conservatives.

“We could talk for hours about that,” Pozen said quoting his own prior article on "Constitutional Bad Faith."

“In a nutshell, I agree that ‘bad faith arguments have been used continuously to delegitimize liberal/progressive jurisprudence.’" To cite an infamous example, he said, “The majority opinion in Bush v. Gore seems to me to be drenched in bad faith. ... Bad faith is all over the place in constitutional law — so much so that the most interesting question is often not whether bad faith is present but bad faith of what kind.”

One of the main accomplishments of Pozen's paper is to develop a taxonomy or field guide of constitutional bad faith, organized on two levels: three broad, generic varieties, and 10 more precisely-defined species. In his introduction, Pozen writes:

Typically associated with honesty, loyalty, and fair dealing, good faith is said to supply the fundamental principle of every legal system, if not the foundation of all law. With limited exceptions, however, good faith and bad faith go unmentioned in constitutional cases brought by or against government institutions. ...

This doctrinal deficit is especially striking given that the U.S. Constitution twice refers to faithfulness and that insinuations of bad faith pervade constitutional discourse. ... [I]n spite of, and partly because of, their uneasy status within the courts, these norms perform a variety of rhetorical and regulative functions outside the courts.

Varieties of constitutional bad faith

At the top level, Pozen distinguishes between three main types of bad faith: First comes subjective bad faith, which “may involve the use of deception to conceal or obscure a material fact, a malicious purpose, or an improper motive or belief, including the belief that one’s own conduct is unlawful.”

He identifies four species of subjective bad faith, starting with “facially neutral government actions that are in fact based on illegitimate motives or purposes,” which might describe Trump’s citizenship census question — if, that is, there were anything "facially neutral" about it.

Second comes objective bad faith, which, drawing on American contract law, “focuses not on the actor’s state of mind but instead on the fairness or reasonableness of her conduct, tested against the norms of a legally relevant community.” In the constitutional realm, Pozen notes, “Many disputes over objective bad faith in constitutional politics concern the interactions among the various institutions of government and a claim of unfair dealing.”

Again, he identifies four species, starting with “unwillingness to compromise or negotiate across branch or party lines,” which has become increasingly characteristic of our politics over the past quarter-century. Trump may be ruder than most, but he’s hardly exceptional. McConnell’s refusal even to consider the Garland nomination was a classic example.

Third comes something more subtle: Sartrean bad faith, “a lie to oneself.” (A reference to Jean-Paul Sartre's classic of existential philosophy, “Being and Nothingness.”) The distinction from subjective bad faith is crucial: “A person in subjective bad faith necessarily understands that she is being insincere, or untruthful in her dealings. A person in Sartrean bad faith may not similarly appreciate that she is being inauthentic, or untruthful toward herself.”

More concretely, Pozen writes, “The waiter in the café who identifies completely with his role and ceases to see that he is playing at being a waiter, to take Sartre’s best-known example, is in the latter sort of bad faith. So is the patriot who manipulates standards of evidence or assessment to sustain a conviction that her own government is uniquely virtuous.”

As Pozen explains, this form bad faith tends to take one of two forms, which in turn give rise to specific forms of constitutional bad faith. Stick with me; this isn't easy material:

“Sartrean bad faith revolves around lies that deny either the full measure of one’s freedom (‘transcendence’) or the concrete details of one’s circumstances and constraints (‘facticity’).” The first of these gives rise to “necessitarian assertion[s] about what the law 'must' mean,” while the second gives rise to “minimizing of inconvenient facts about the Constitution and the judicial role.”

Furthermore, each of these is associated with a specific ideological pole:

Whereas originalists tend to be charged with Sartrean bad faith for denying their own transcendence, living constitutionalists are more likely to be charged with Sartrean bad faith for denying the facticity of their situation: the concrete constraints that come with a written Constitution and the social expectations it generates … . The alleged bad faiths of our culture’s stereotypical originalist and its stereotypical living constitutionalist are mirror images of one another.

These are fair readings of the dangers inherent in these positions. But note that Pozen says “alleged bad faiths.” Given how freely conservatives overturn precedents, it’s not clear that "living constitutionalists" (i.e., liberals or progressives) actually deny "concrete restraints" more than conservative "originalists" do.

Bad faith at the Supreme Court

Evidence of conservatives’ outsized "Sartrean bad faith" is overwhelming, as the Supreme Court's landmark 2008 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller is sufficient to show. In that 5-4 decision, the court's conservative majority struck down a key gun control act of 1975, finding that the Second Amendment conferred a broadly defined right for individuals to own firearms.

One can imagine an alternative universe, with a far different history and constellation of current facts, in which a "living constitutionalist" interpretation of the Second Amendment could find good-faith justifications for ignoring the plain text that defined its purpose and intent: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State."

But there is simply no way for an "originalist" reading of the text to arrive at the good-faith conclusion that the amendment was intended to apply to all individuals, with little or no restriction. Yet here we are.

The story with the history-shaping Bush v. Gore decision that decided the 2000 presidential election was similarly stark, although the details get messy. But former Yale and Berkeley law professor Robert Post has stated it clearly enough:

"I do not know a single person who believes that if the parties were reversed, if Gore were challenging a recount ordered by a Republican Florida Supreme Court," that Justices William Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas "would have reached for a startling and innovative principle of constitutional law to hand Gore the victory."

It’s worth noting that a 7-2 majority in that case found a violation of the 14th Amendment because imperfectly-marked ballots weren’t being uniformly counted or discarded — but only the five conservatives ("soft" conservatives Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, plus the three named above) voted to denying any lower courts an opportunity to remedy that violation.

It was as clear a distinction between good-faith and bad-faith reasoning as one could possibly want: Denying the opportunity for a judicial remedy made certain that none of the questionable or uncertain ballots would receive any protection at all. “Protecting” voters' rights by destroying their ballots is bad faith par excellence.

Geoffrey R. Stone, an editor of the Supreme Court Review, noted that over the previous decade, the three hardcore conservatives had cast 65 votes in non-unanimous decisions interpreting the Equal Protection Clause, 19 of which involved affirmative action. Collectively, the conservative justices cast exactly two votes finding Equal Protection Clause violations those cases — one less vote in an entire decade than they cast in the Bush v. Gore decision. Summing this up, Stone wrote:

What does this tell us? It tells us that Justices Rehnquist, Scalia and Thomas have a rather distinctive view of the United States Constitution. Apparently the Equal Protection Clause, which was enacted after the Civil War primarily to protect the rights of newly freed slaves, is to be used for two and only two purposes — to invalidate affirmative action and to invalidate the recount process in the 2000 presidential election.

A clearer example of constitutional bad faith would be hard to imagine. It dovetails perfectly with the historical account that Maxwell provides, except for the part about bad-faith arguments not holding up in court.

As the dust settles on the debacle of Trump's "census question," it’s imperative to pay attention to the bigger picture. Suppressing the count of undocumented immigrants was only one part of the overall scheme to “reestablish the foundations of white man’s government,” as Serwer succinctly put it. Already, as NPR’s Hansi Lo Wang noted on Twitter:

This is the next step in securing white minority rule through 2030. Basing representation on "citizenship voting age population," rather than total population, would be a radical departure from American tradition — just the sort of radical departure that bad-faith originalists love. It would allow Republican-controlled states to dramatically increase the number of seats elected by older, whiter, more rural districts, making infamous partisan gerrymanders like those in Wisconsin, Michigan or Ohio even more extreme than they already are.

There is growing popular support for a fairer redistricting process that does away with partisan gerrymandering. (It's true, after all, that Democrats have done that too — although not nearly as much.) But the Supreme Court is pushing back hard. On the same day Chief Justice John Roberts turned away Trump’s census question, he also turned back any possibility of a federal court remedy to partisan gerrymandering, effectively giving a green light to the larger white supremacist project in which the flawed census question was a weak link.

Bad faith in “balls and strikes”

It’s often said that Roberts cares deeply about the perceived legitimacy of the Supreme Court. That's clearly true. But as the above summary suggests, that perceived legitimacy is itself a bad-faith fiction. Roberts is doing everything he can to ensure continued Republican rule while maintaining the illusion (perhaps to himself as well) that he is just “calling balls and strikes.”

Even the metaphor is a lie. Trial court judges may call balls and strikes, but appellate justices decide which game is being played, and which set of rules apply. Every lawyer in America knows that, and to pretending otherwise is just more bad-faith posturing. Roberts excels at that, and his bad faith is far more dangerous to America than Donald Trump’s.

Trump’s bad-faith arguments, after all, are transparent, garish and impossible to miss. Roberts’ bad-faith arguments are subtle, fashionably attired and cloaked in intellectually respectable language. Almost everyone yearns to believe that the Supreme Court is above politics, that it represents a pure, hallowed realm where American ideals are preserved. That may be the biggest and most dangerous bad-faith lie of all.

Shares