At a time when comic books are regularly adapted into superhero movies, George Takei’s new graphic memoir “They Called Us Enemy” involves heroes who would also work wonderfully on the silver screen. To be sure, the main characters don’t wear colorful costumes or use superpowers, but they are heroes nonetheless — and what they do, in the face of evils no less than those posed by fictional villains, is pretty super too.

And at a time when President Donald Trump has become a real-life villain to countless innocent people wronged because they are immigrants and not white, it’s a tale that desperately needs to be seen by as many people as possible.

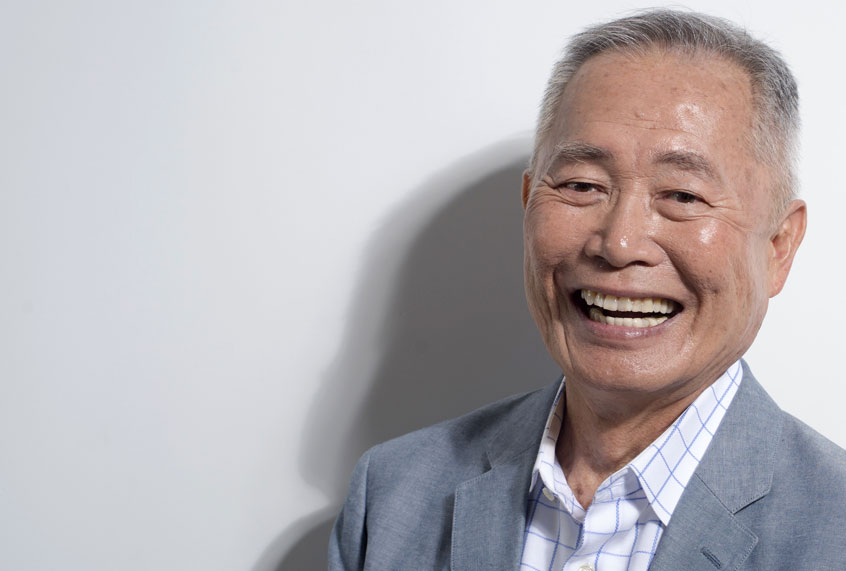

“They Called Us Enemy” tells the story of how Takei, the actor best known for playing Hikaru Sulu on the classic TV show “Star Trek,” was imprisoned at internment camps along with his parents, siblings and roughly 120,000 other Japanese Americans during World War II. It’s a shameful chapter from American history with eerie parallels to the present: President Franklin Roosevelt, succumbing to the racism that permeated the political zeitgeist of his time, decided that Americans of Japanese descent could not be trusted after the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and dragged America into global conflict. Consequently he issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which began a process that culminated in Japanese Americans from the West Coast being forcibly relocated to squalid detention centers through most of the early 1940s.

In telling the story of his experience being wrongfully arrested and interned, Takei repeatedly notes how because he was a young child at the time, his innocence protected him from much of the trauma that others in his situation endured. Nevertheless, his recollections are harrowing, from the ease with which he and his fellow Americans were stripped of their humanity to his observations about the anger and despair felt by many of the inmates about the blatant injustice of their situation.

If anything, the story is more poignant precisely because he includes little details that ring true for anyone who remembers their early childhood — of being fascinated with the clickety-clack of a secretary’s typewriter, timidly meeting a giant hog owned by a kindly Arkansas farmer, getting tricked by an inmate into swearing at one of the camp guards or being told that the barbed wire around their facilities were intended to keep out dinosaurs. These moments not only add lightness to an otherwise dark tale but also reinforce the sadness, because we realize that all of these terrible things are happening to a little boy, one so far removed from the politics and atrocities of the outside world that he can mistake his situation for being an adventure.

Yet there is also much that is quite inspiring in Takei’s book — namely, the real-life heroes who stand up in the face of terrible adversity, either for themselves or others. There are the Japanese Americans like Takei’s father Takekuma Norman, who helped other inmates by serving as a leader and translator, and his mother Fumiko Emily, who made clothes, curtains and rugs. There is Herbert Nicholson, the Quaker missionary who risked his physical safety to bring books, donations, personal effects and even a loved one’s cremated remains to internees, as well as helping their pets go to vets, and Wayne Collins, a lawyer who defended Japanese Americans who had been pressured into renouncing their citizenship while interned.

There are the countless Japanese Americans who stood up to the government in various ways for stripping them of their constitutional rights, as well as those who chose to fight for their country as soldiers in World War II despite the injustices which had done to them (Takei wisely recognizes the merits in both positions and simply explains why different people made different choices given the situations in which they found themselves). And there is Takei himself, who developed a passion for social justice issues that is almost certainly connected to his growing understanding as an adult of what he only dimly perceived as a child, and which has made him a leading voice today for progressive causes including those of LGBTQ rights and marriage equality.

If the comic book craze is going to continue to boom in Hollywood, the least producers can do is adapt graphic novels like this one to the big screen so that people can be educated about the real heroes and villains from a not-too-distant time in America’s past. Even if that doesn’t happen, though, “They Called Us Enemy” cannot be recommended highly enough, as Takei and his co-writers Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, as well as artist Harmony Becker, have created a true masterpiece. At a time when America is once again putting people in concentration camps by wrongly labeling them criminals — and continues to struggle with its ignominious heritage of racism, xenophobia and outright cruelty — this story remains painfully, vitally relevant.

I spoke with Takei by phone recently about his book, that period in American history and its current parallels. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Near the end of your book, you discuss the reparations that were received by survivors of the internment camps and the official apology that was given to them. Do you think the American government owes reparations to the immigrants and migrants today who have been mistreated by the government, whether by being separated from their families or held in inhuman detainment, or just were deported despite not hurting anyone? And what about other groups that have been currently wronged or were wronged historically, such as the descendants of slaves?

I believe this is a larger and much more complex issue that you talk about. I really haven’t thought through the issues involved with the current situation, so I really can’t comment on that. With the history of slavery that we have, its legacy has continued, but the current African Americans are not slaves, but they are suffering from police brutality, the mentality of the police to see African Americans as a degree more dangerous and unpredictable than others, and they are quick to shoot, or other discriminatory factors. So I think the solution there is more institutional, where there has got to be institutional change and also some legal reforms, more money for them to have better educational opportunities.

Yes, we attempted busing for integrated education after Brown v. Board of Education, but that is now still currently a real part of the real political discussion. . . .

I don’t believe Kamala Harris — because we Californians, Japanese-American Californians, have had a different experience with Kamala Harris and it’s been very destructive to the Japanese American community today — but, nevertheless, Biden’s background on busing has become an issue. So there needs to be serious thought given to the educational opportunities and some education compensation programs, to right the situation.

The Japanese Americans did get a formal apology, President Ronald Reagan did officially and on behalf of the U.S. government apologize for it. He did sign the Civil Liberties Act, which paid a token redress of $20,000.

And it is relevant to the larger story of the African American heritage as well as what’s going on at our southern border. But I really haven’t given that much thought to the consequences of the southern border. That outrage is still ongoing and spiraling down. We’ve reached a new low.

In our case, we were children intact with our families, our parents. But, in this case, it is really tinged with evil because not only are they separated, but torn away from their parents. But rather than being kept where they were torn away so that they can be reunited, they are randomly scattered in outlying areas like Minnesota or Wisconsin or New Jersey. And when they’re ordered by the courts to be brought together, they can’t do that, they’re so incompetent.

So it is an ongoing issue. But the book is about the restitution and apology that we campaigned for and the survivors who were still alive. But in the case of our family, my father was the one who bore the pain and the anguish and the degradation the most. And yet he was able to teach us about American democracy, of people’s democracy. But he passed in 1979. So one of the great tragedies that came from, in our family, out of the redress was the fact that our father died never to know that there was going to be this apology and restitution, because the apology and the restitution was to the survivors, those that were still living. Those who had passed were not . . . their share of the restitution was not given to my mother, his widow. So it was a bittersweet achievement in our campaign to get that apology.

I was active in the movement. I testified at the congressional hearing. And I did it on behalf of my parents and both my brother and baby sister. But the one in our family that suffered the most did not live to know that there would be that apology. And that was a big thing. That would have been the big thing for my father.

There’s a section in your book that was really powerful where you describe how your father never abandoned his belief in democracy, never abandoned his belief in the good of America. But at the same time, he was obviously deeply wounded by the way that he had been mistreated by his own government. And I feel like there is a larger lesson there. How does one balance paying respect to the good that exists in this country while at the same time being brutally honest, if necessary, about the evil that our country has done, including to Japanese Americans?

Yes. By sharing our experience with American democracy. I wrote my autobiography in 1994, and then in 2015, we developed a musical on the internment of Japanese Americans and we played on Broadway. It’s called “Allegiance.” Now we’re coming out with this graphic memoir and also, there will be a major ten-part miniseries on the internment of Japanese Americans, coming out next month [on AMC] titled “The Terror: Infamy.” These are all efforts to raise the awareness of that history so that we educate other Americans on a little-known chapter of American history. Hopefully there are people who cherish the noble ideals of our democracy and will work to make this a better, truer democracy.

Your graphic novel does discusses parallels between what happened to Japanese Americans in the 1940s and, for instance, the Muslim immigration ban passed by President Trump. When drawing those parallels, obviously, there is the risk that people will say that you’re being too political. Where do you decide to say those experiences from the past are relevant today and they need to be brought up?

Well, it is political, and it’s politics that put us into those barbed wire camps. And it’s politics that’s behind the humanitarian outrage that’s going on on the southern border. The solution is political. To get people who really, truly honor the noble ideas of our democracy: All men are created equal. Or to understand that seeking asylum is a human right. And this politician in the White House is an ignorant one who doesn’t know the history. Both the internment of Japanese Americans then and the Muslim travel bans, together with the humanitarian outrage at our southern border now, were political acts. We have this endless cycle of repeating the cruelty and the injustice every so many decades, and it’s happening again. By having more Americans who are mindful of that history, and that’s the intent of the book, to teach this to a young leadership so that they grow up knowing this history, so that they all work to try to avoid repeating this failure of our people’s democracy.

In your book you mention how Earl Warren and Franklyn Roosevelt laid the foundations for the internment policies, even though they are admired today as the architects for important left-wing social and economic policies through the Supreme Court [Warren was chief justice from 1953 to 1969] and the White House [Roosevelt was president from 1933 to 1945]. What lessons should liberals learn from the fact that two of their own heroes committed these horrible actions?

When I was a teenager and I had these long after-dinner conversations with my father, he told me that our democracy is a people’s democracy and the people have the capacity to do great things . . . but they are also fallible human beings. Great people are also fallible humans and can make great mistakes. But there are also those extraordinary people, like the governor of Colorado in the early ’40s, Ralph Carr, who had the courage to speak out against the hysteria of the times on the fundamental ideals of our democracy. People like Ralph Carr, the strong pillars of our democracy are evidence of that.

The people are also fallible human beings and we make mistakes. And, as President Reagan acknowledged, President Roosevelt made a grave mistake. So I think intelligent people who are well-informed will do everything we can do avoid making those human mistakes, human fallibilities. But that’s organic to us as fallible human creatures. So we do everything we can to try to prevent that by being as informed of the dangers of American history and doing all we can to avoid it.

This book is a part of it, as was my Broadway musical. We founded a museum in Los Angeles called The Japanese American National Museum, which is affiliated with the Smithsonian. The museum is an effort to institutionalize the story. The Broadway musical is an effort to humanize the story. And “They Called Us Enemy” is also to share this human story with a young adult and youth leadership.

Now, people who read this story, what lessons do you think they should learn from it in terms of contemporary issues, like the immigration crisis at the southern border, like the question of Muslim immigration and Trump’s ban on them?

Let me try to put together how all this effort relates to our situation today, the Muslim travel ban and the outrage on the southern border.

Well, when we were incarcerated, all of the elected officials made sweeping ignorant statements, generalizations that we’re potential spies, saboteurs, fifth columnists, with no evidence of that. And now what’s being done is sweeping statements characterizing all Muslims as potential terrorists, or Latinos coming across the southern border as drug dealers, rapists, and criminals. And that man in the White House saying the immigrants came in illegally and we’re going to take them out legally.

Well, the criminals are illegal, but all of them are not illegal. I mean, they are exercising their human right as asylum-seekers fleeing violence and poverty. Some women have seen their husbands murdered right in front of them, and they’re fleeing for their lives and their children by coming here. So I hope that what we learn is to condemn people who make these sweeping, gross, outrageous statements characterizing a whole people with negative characteristics. That is what’s happening with the Muslims as potential terrorists, and with Latinos coming across the border as criminals and rapists and drug dealers.

It’s interesting, because people will say, ‘Oh, if I had lived in the 1940s, I would have opposed the internment policies.’ Yet it seems like many of them really would not have. How does one assess whether they would have done the right thing as an individual if they had been alive during this period? Because most people today would say that what happened to Japanese Americans was wrong — but that doesn’t mean they would have said it at the time. Do you see the point I’m making?

I do. And those people were ignorant people. They didn’t know. As a matter of fact, during the 2016 campaign for the Democratic and Republican nominations, Donald Trump made that statement, that we’ve got to have a total and complete ban on Muslims coming into the United States because they’re terrorists. Well, at that time, I understood that to be clearly an ignorant statement, that someone who doesn’t know the American chapter of American history where we were incarcerated. And so, because I did “Celebrity Apprentice,” I know Donald Trump. As a matter of fact, I had a private lunch with him, as a guest, to discuss marriage equality. And so I sent him an invitation to come see “Allegiance.” And I said I’d love to have him as my guest and I sent a private invitation to him. But also I made it very public by going on morning talk shows, afternoon talk shows and evening talk shows. And, we took an orchestra aisle seat and put a great big sign on that seat saying, “This seat reserved for Donald Trump.”

Because I took him to be an ignorant person who doesn’t know the history, so I thought I’d help him be informed on American history and, particularly, the chapter of our internment. He never responded to that. So to this day, he is willfully ignorant of that history. That’s why we’re making this effort to raise the awareness of history, so that we have more people who are informed and they outnumber the ones that are ignorant.

When you interacted with Trump personally, I have to ask, what were your impressions of him? Did you imagine at the time that he would be the kind of person who would do what he has done?

The issue that I was advocating with him was marriage equality. New York did not have marriage equality then. And so I thought I would have a private discussion to try to persuade him. When we got together, I told him that you’re a businessman. Marriage equality would be good for your business. Gays and lesbians throughout the country would love to come to New York and get to stay in your hotels, eat in your restaurants, maybe even get married in one of your banquet halls. Even New Yorkers outside the city will come down to New York, and so the economy of New York City would become vibrant and you would be the beneficiary.

He said, “Yeah, that’s true. But I believe in traditional marriage.” I was taken aback by that and that he would use that as an argument. But I reined myself in, because I knew that he was on his third marriage and he had been famously unfaithful all through all three of his marriages. But I remained silent about that. I said, “Yes, I believe in traditional marriage as well. A traditional marriage is where two people who love each other, who are committed to each other, and they are committed for life. And if a vow is through thick or thin, in sickness and in health, and that is what I consider someone who supports traditional marriage.” And we went back and forth and we never got anywhere. We finally concluded by agreeing that we are going to disagree.

But he is a person that will accept invitations to discuss issues. In fact, when I invited him at a press conference, he said, “You know, that’s going to be an interesting conversation.” He was open to it. But, clearly, when he is in power, he has demonstrated that he is not open to seriously considering that. I consider him willfully working at his ignorance remaining that way.

[One of Takei’s assistants says something inaudible in the background.]

Leigh here just suggested that we send this book, as I sent him an invitation to “Allegiance.” We’ll send him a copy of “They Called Us Enemy.”

I mean, he does have a reputation for having a short attention span, but it is a graphic novel, so maybe that’ll compensate for it.

Well, this is aimed at the youth leadership and young adult leadership to inform them. I think there are mature people in positions of great power who also are ignorant and could use the information in “They Called Us Enemy.”

[In your book,] at one point you write, “Memory is a wily keeper of the past, usually dependable, but at times deceptive. Childhood memories are especially slippery, sweet, and so full of joy they can often be a mis-rendering of the truth.” You were at a young enough age that is seemed like you didn’t fully understand the situation, at least at times, and that somewhat protected you. Yet, that wasn’t true for all of the children who had been wronged by the American government, whether you’re talking about current policies implemented by Trump or whether you’re talking about throughout history. What advice would you give to children who have been impacted, who have been traumatized by the policies of the American government or by other governments?

We have reached a new low where, when we were incarcerated, we were protected by our parents. My father told me we were on a long vacation in this place called Arkansas. And for this southern California kid, it was an adventure of discovery. But these children that are put in cages have no parents to give them any guidance. In fact, they’re treated like animals and their lives are going to be severely damaged by this experience. So, it’s not advice that we can give, but a show of compassion: Don’t tear the children apart from their parents. Keep them together. At least that’s a modicum of some kind of protection for the children you have. I was together with my parents throughout and we went through harrowing experiences when we were transferred.

The outrage of demanding loyalty after they strip you of everything that you built up in life, of frozen bank accounts, which meant that we lost our home, my father’s business, totally stripped. . . . And then to be placed in a barbed wire prison camp. And then, a year after that imprisonment, to have the government demand loyalty to this government. And my parents stood on principle and said, no, we will not. The question was very ignorantly put together by someone who doesn’t know the English language. And so, we were imprisoned in another camp.

Are you sympathetic to people who are angry at the government and say that it doesn’t deserve their loyalty unless that respect is reciprocated?

Well, there has to be unconscionable governmental transgression, a real good reason. If you read my book, you know that my mother was goaded and coerced into renouncing her American citizenship. The behavior of the government was so reckless and so cruel, evil, that that was the only way she could protect her family. So it depends on the circumstances.