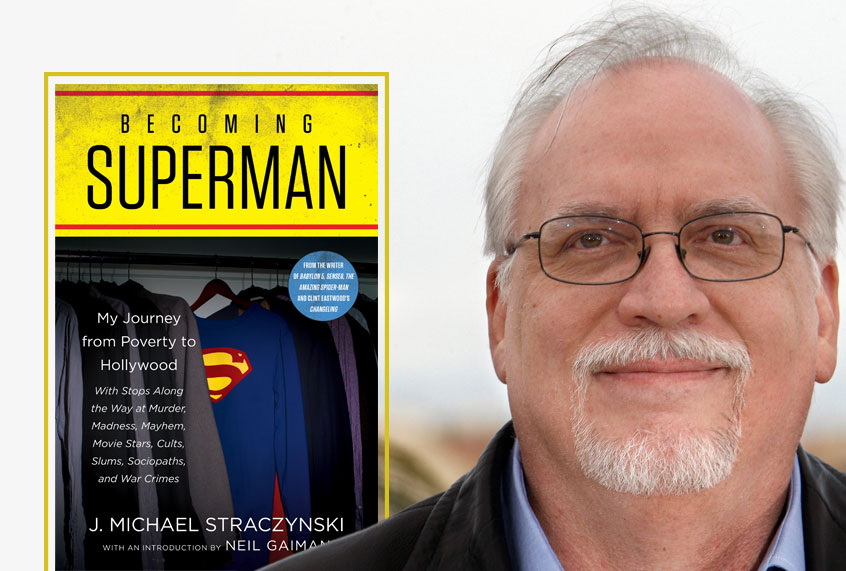

J. Michael Straczynski’s new memoir “Becoming Superman: My Journey from Poverty to Hollywood” is a story of adversity, struggle, triumph and perspective. As a child and young adult Straczynski suffered horrible physical abuse and emotional neglect from his father. Later in life Straczynski discovered that his father was a Nazi sympathizer who participated in horrific crimes. The sins of the father are sometimes the sins of the son: Straczynski’s grandfather was a con artist who seduced his own niece.

Families also have legacies, deep tendrils of pathology: Straczynski’s mother was abused by his father. She was also a sex-trafficked child who Straczynski’s father de facto kidnapped and then married. Straczynski’s mother, suffering from severe depression, also tried to kill him when he was a child.

J. Michael Straczynski also wrote the 2008 film “The Changeling” which starred Angelina Jolie and was directed by Clint Eastwood.

Straczynski is one of the most influential voices in all of American (and global) popular culture yet few people among the general public know his name. And despite all of his life successes, J. Michael Straczynski remains humble.

Straczynski is a very private man. His sharing makes for a story that is at times so unbelievable that it must somehow be true. In an earlier era long ago, “Becoming Superman” would be part of the penny press or dime novels, sold to kids and young adults alongside “The Horatio Alger Myth.” But Straczynski’s “Becoming Superman” would have the words “This All Really Happened!” emblazoned on the cover — and in Straczynski’s case, that would not be marketing bluster. Those words would actually be true.

Ultimately, even a writer as gifted as J. Michael Straczynski could not have invented such hardships and then the winding twisting route that is his life — and then be able to share these details in a compelling way. But in so generously and honestly telling the truth of his life, he has again shown himself to be a master storyteller and a uniquely gifted writer.

In this conversation J. Michael Straczynski shares life lessons about overcoming adversity and how pain can be fuel. He also reflects on the craft of writing and offers advice and insight about writing on political and social issues in a dire moment such as the Age of Trump. Straczynski also shares his thoughts on if his TV series “Babylon 5” was copied by “Star Trek Deep Space Nine”, and what really happened with his script for the “World War Z” movie.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How does it feel to finish the book and have it in your hands? There is so much honesty here. You have now shared your most inner private self with the world.

I have a range of emotions. On the one hand, I’m glad that I have the book out in the world because you are trained when you’re a kid that everything that happens inside the house stays inside the house. If you talk about it somewhere else, unspecified but terrible things will happen to you. And even when you grow up, there’s some part of your brain that still keeps repeating that over and over again — which is of course the tyranny of it. There’s still part of my brain that goes, “When this comes out, you’re going to get in trouble. Just wait until your father gets home.” Having sat on this information for so long, there’s a part of me that’s just very nervous about the process of sharing. But those people who have read the book have been very kind in their responses. This is cathartic.

When you were writing the biography there had to be moments where you said to yourself, “I have to stop. This is too much.” How did you keep on going?

You’re absolutely right. There were times when I was writing the book and I just had to put it away for a while. It got too raw or too personal. I would put it aside for a couple of days or a week and sometimes even a month until I could gird up my loins to go back in there and write some more. The key for me in writing my story was that it could not be overwrought where it is something like “Oh my God, this is what happened. Poor me! This is awful!” I didn’t want it to be too dramatic or overly emotional. These are just the events as they happened to me and I experienced them. No embellishment is necessary.

I think that the moment you start offering up some narrative centered upon “Oh feel sorry for me” you are then overwriting the story. You are playing the victim in a lot of ways. I don’t believe in that. I think that the moment you define yourself as the victim is the moment you stop existing as your own person. Now that becomes your definition for life as opposed to choosing your own path. So the hardest part of writing my biography was really just keeping what happened to me a bit at arms length, balancing those horrific things with some measure of humor from time to time, and dealing with it more as a journalist. Having been a reporter for a while, I know how to talk about things in a fairly dispassionate fashion.

How did you decide what part of your story is for you and what part do you share with somebody else? Can you lose a part of yourself by sharing too much with the public?

That is difficult. In a way the book provides that balance because I spent the preceding 40-plus years of my life as a sentient human being not discussing my life and now I have shared it. When I’d be interviewed by journalists, reporters or just fans at conventions they would ask me about my personal life and I would just make a joke or avoid the subject.

In terms of the art, I always write for myself. I never really stop to think about who is the audience or how my work will be perceived because one does not know that answer ahead of time. That’s why I always tell writers, write what you’re passionate about right now. Don’t second guess yourself. Don’t think about the marketplace, don’t think about the audience. What are you annoyed by? What’s stuck in your throat or what is it in the back of your head that you absolutely have to get out? Stay with that passion and the rest will take care of itself.

Considering the political tumult and misery in the United States and elsewhere, what advice would you give to a journeyman writer who wanted to write a comic book, graphic novel, TV show, or other creative work which “speaks” to this moment? Who wants to write something “socially relevant?”

When you want to write “politically” — and that’s your initial impetus going forward — you have to be careful because you do not want the work to turn into a polemic or a dialectic. If you start pulling the social commentary too far into the foreground then you will alienate readers on the other side of the issue. Whereas if you wrap it up inside a character or a story dynamic that is compelling on its own terms then it becomes more palatable and therefore more enduring for the reader.

A number of years ago I worked with James Cameron on a project and he said one of the smartest things to me I’ve ever heard about writing science fiction. He said, “I used to think that writing science fiction was about writing unfamiliar characters in unfamiliar settings. It took me 10 years to realize I was wrong. It’s writing familiar relationships in unfamiliar settings.” So “Terminator 2” was a father-son relationship — even though it’s not. “Aliens” is a mother-daughter relationship — even though it’s not. You may not be able to buy into robots or space travel or aliens but you as the viewer or reader can buy into those relationships.

For example, in “Babylon 5” I constantly brought in issues of politics and religion. I’m an atheist. I don’t agree with religion. But if I make it about me not agreeing with religion, then I’m pushing my views on the audience rather than saying, “Okay, how do we deal with this fairly, honorably and respectfully, but yes, we will be free to criticize these themes.” It’s really just a matter of balance. I am not going to put my finger in your eye until you hear what I have to say. You have to be gradual about the process.

How have you disciplined yourself to foreground that human voice? For example your television series “Sense8” is so powerful precisely because of its themes of empathy and human dignity and the importance of intimate sincere human relationships. Is your emphasis on empathy intentional or just a basic part of who you are?

I think it’s a little bit of both. The reason we made “Sense8” was that we as a culture have been factionalized, tribalized and marginalized to the extreme. If we in America were divided geographically right now as we are politically we’d be hearing gunfire in the distance. Therefore, I wanted to do a story that said “No. We are better together than we are apart.”

“Sense8” works so well because that’s how I feel on a regular basis. I believe in our shared humanity.

Do you think many Americans are afraid of the future? Right now there are very few big ideas and hopeful visions. We as a country have become so narrow and dystopian.

I’m sure there are folks out there watching “Handmaid’s Tale” thinking, “Oh, someday we’ll get there. Someday we’ll achieve that goal.” The problem is that among our elected officials no one is really talking about the future in America. We deal with our problems on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis…if even that much. There’s no one here like a JFK saying we must go to the moon or plan to build highways, or expand the limits and boundaries of technology. Absent that, it is the role of science fiction to point to that horizon. When we lose our way as a people, when we are sold on the idea that we must be divided then we must attack each other. We are seeing this right now in America. We are looking at our collective feet to avoid stumbling instead of looking to the horizons of great possibilities.

The goal of science fiction — and what should be the goal of politics — is to get people to look upward, to raise their eyes to the horizon, and think about what’s coming down the road at them. If you don’t do that, if you’re not willing to or able to look down the road, then fear is a natural consequence. The future becomes something scary or unmanageable which is what we should avoid if we are to have a healthy society.

You have written across genres and formats. What are your thoughts on the state of comic books and graphic novels and how they have now, for the moment, conquered Hollywood and global popular culture?

The answer depends on who you talk to. I know that comic sales are in a slump right now. However, comic book movies are doing really well. This may be more true for the Marvel comic book movies because they tend to be more joyful. Even when there are terrible things happening in the stories you sense a strong bond between the characters. Whereas the DC movies tend to be a little more dystopic, a little more hard-edged and thus a little more cool to the touch.

Thinking about a classic, why does Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner” still endure some 40 years after it was first released in theaters? I have to wonder how many of these most recent comic book superhero movies will stand the test of time.

Films and books that address core human questions are the ones that will always survive and do well. Those core questions will be around 30 years from now. They will be relevant then as much as they are now. “Blade Runner’s” core themes are very fundamental. We don’t have a lot of time and that’s not fair. Because time is so fleeting, we have to get as much experience as we can in there before the game is called on account of darkness. “Blade Runner” is all about the fragility of life. This is true whether you live 60 years or you live six years depending on what the programming is. Life is still finite. We are not going to live forever. What “Blade Runner” does is it says, “realize now how finite your life is. What are you doing at the moment?” Yes, it is unfair that we only have this brief window of time. But if we only have that amount of time then we should live it to the hilt.

That is a direct connection to your biography. You are relentless in terms of pursuing your goals. Where did that mania come from?

I don’t think I really have a choice. Writing isn’t just what I do, it’s what I am. I come from hard circumstances and everyone around me kept saying, “You’re never going to be a writer.” I learned to fight. And I also learned to fight against anyone who said that I wasn’t going to be a writer.

I’ve always had someone telling me that it wasn’t going to happen: Kids like you from the neighborhood you come from, your career options are crime, prison, Walmart, or death. I never bought into that. There’s always someone that would tell me “you can’t do it”. Whenever someone says to me “You can’t do that” my immediate response is to fire back, “Not only can I, but I will just to spite you.” I could never back away from the writing because that’s all I am. If I didn’t have that, then who the hell am I? Everyone in the world kept coming after me, but I just kept going anyway.

Is your pain a type of fuel?

When you come through horrific circumstances, having lost everything I ever owned multiple times, the idea of losing everything again really isn’t that terribly scary. I mean, if tomorrow, and I love my house and my environment, and just my surroundings and the life I’ve built, but if tomorrow the whole house burned down, that’s life and you move on. When you are up against powerful forces, studios and executives who have power over your career for example, after a while you realize they can’t kill me, they can’t eat me, they can’t put me in TV prison, and there’s nothing they can do to me that’s any worse than what I already went through, then why not stand up on your hind legs and say, “By the way, you’re wrong.” It does give you a certain fearlessness.

All things considered, would I have preferred to have avoided a lot of that? Yes. But it also made me realize that I had a choice in my life. Growing up in the cycle of violence and brutality and the alcoholism and everything else that goes back five generations in my family, I am what I am because I was born that way. This was my culture. This is how I was raised. My gospel is the gospel of choice.

You don’t have to be what you were born into. You don’t have to do to somebody else what got done to you. You do have the power to choose. The moment you say you don’t have a choice you have made a choice.

I have shared this with other comic book writers and graphic novelists whose work I respect and admire. When I was a child my favorite characters were (and still are) anti-heroes such as the Punisher and Wolverine. I didn’t begin to appreciate Superman until I was much older. Why do you think that is?

For example, “The Transformers” TV show and similar shows back in the ’80s and ’90s are power fantasies. These shows are about having the power of a giant robot or some other great abilities. Kids are powerless for the most part. They are told where to go, where to eat, where to sit down, when stand up, to go to school. An idea of a power figure is really attractive to them. As one gets older and learns more nuance then the idea of restraint becomes more important. One also learns from a character such as Spider-man that with power comes great responsibility. Children don’t have responsibility so they choose power.

As you get older there is an element of responsibility. Our tastes become more mature. Our interests in music become more mature.

For me, the reason I liked Superman as a young kid was he always made the moral choices. This was very important to me because I did not have a proper father figure or other authority figure in my life. Superman never hit someone who didn’t hit him first. A family like mine lacked any kind of moral compass whatsoever. Superman showed me that there is a better way to live. There is someone who would look out for me. There’s someone who if I was in a bad situation would protect me as opposed to hitting me. I responded to Superman’s restraint as much as I did to the notion of this is someone who cares. One reason why Superman is also called the Big Blue Boy Scout is that he wears his heart on his blue sleeve.

“Babylon 5” is one of my favorite TV series of all time. Why is there such a renewed interest in the show at present? Or has the interest always been there? “Babylon 5” really is a precursor to the style of storytelling that is common for so-called “prestige” television shows right now.

“Babylon 5” is a five-year arc. When we started the show television was very episodic. At the end of a given episode the reset button is hit. That structure was very important for long-term syndication. I wanted to do a story that has a beginning, middle, and end, where each year is corollary to the five points of a novel, the introduction, rising action, complication, climax, and resolution. “Babylon 5” is structured exactly this way.

Warner Brothers didn’t want me to do that with “Babylon 5”. They said it’s not going to work and that the audience does not have the attention span for it. The executives thought that the most an audience could handle was a two-part episode. I had to fight like hell to get that motif going. But one of the great things was after seeing “Bablyon 5” get going and its influence on so many other shows. Damon Lindelof who wrote “Lost” told me, “We kind of borrowed your structure.” Ronald Moore sent me a copy of the pilot script for “Battlestar Galactica” and it also had a similar multi-year structure. We’re at a point now, literally where pitch a network a new series and they all wonder where’s the arc? Where does it go in five years?

What is the final word of the consensus in terms of “Babylon 5” “inspiring” “Star Trek Deep Space Nine”?

I can’t speak to what the census among fans is. But my book does cite someone who was working at Warner Brothers who has more inside information on that point. Here is something that is not in the book which is quite compelling. Peter Jurasik, who played Londo on the show, was at a party and one of the primary actors from “Deep Space Nine” was also there. He came up and pulled Peter aside and said, “Listen, all of us on our show know that it comes from your show, and we wanted to tell you good luck because we want to see you succeed.”

There’s no question in my mind certainly that we were ripped off for a number of different reasons. There had never been a show set on a space station in all of TV history until we came along with “Babylon 5” and then “Deep Space Nine” appeared on the scene. It only happened once during a brief window of time. Was one copied on the other? Well, look at the reality of it. To me, it’s pretty obvious. Over time that seems to be the consensus.

What happened with your script for the “World War Z” movie? I have spoken to Max Brooks on several occasions about this — his original “World War Z” book is so very special and smart. Your script was so much better than the movie that was finally produced.

Max Brooks is an amazing writer and “World War Z” is a terrific book. Paramount bought it and had no idea what the hell to do with it because of the book’s documentary-style narrative and structure. There are so many characters who are not really connected to each other beyond the experience of surviving the zombie outbreak. I wanted to write something that would bring a measure of real storytelling to the zombie franchise and make it a much more human story. I’m very happy with the 12 drafts I did of “World War Z”.

Then on came the director and he wanted to make it more of a run and jump story. I was not thrilled with that. So they brought in other writers who would do that. I just think you could have had all the benefits of zombie film but also a really cool character-driven story as well. To see that catalog of missed opportunities just breaks my heart because Max’s book was just so good and so well thought out. To have the “World War Z” movie not really reflect that complexity was, in my opinion, a great loss.