The U.S. Department of Energy wants to redefine what constitutes high-level radioactive waste, cutting corners on the disposal of some of the most dangerous and long-lasting waste byproduct on earth — reprocessed spent fuel from the nuclear defense program.

The agency announced in October 2018 plans for its reinterpretation of high-level radioactive waste (HLW), as defined in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) of 1982, with plans to classify waste by its hazard level and not its origin. By using the idea of a reinterpretation of a definition, the DOE may be able to circumvent Congressional oversight. And in its regulatory filing, the DOE, citing the NWPA and Atomic Energy Act of 1954, said it has the authority to “interpret” what materials are classified as high-level waste based on their radiological characteristics. That is not quite true, as Congress specifically defined high-level radioactive waste in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, and any reinterpretation of that definition should trigger a Congressional response.

One state is fighting back. An amendment was added to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, which passed the House on July 12, blocking any reinterpretation of high-level radioactive waste for the state of Washington by the DOE. The bill is now in the Senate’s hands.

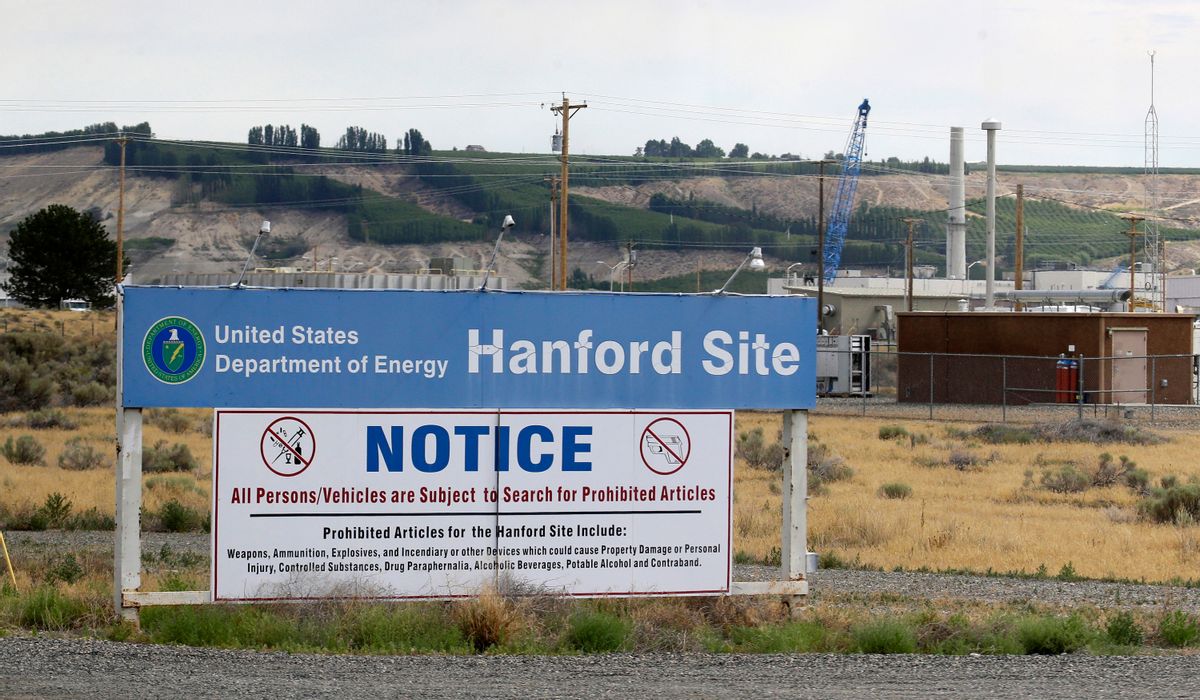

Most toxic place in America

Washington is home of the Hanford Nuclear Site — also known as “the most toxic place in America”, which produced plutonium for the nation’s nuclear weapons program some 70 years ago in the throes of the Cold War. That site has been in a cleanup mode for 30 years, and the DOE is spending $110 billion to clean up 56 million gallons of chemical and nuclear waste stored in underground tanks. That task is expected to last possibly another 50 years. Hanford has also been called “an underground Chernobyl waiting to happen” because if just one of the nearly 200 tanks explodes, it could be catastrophic.

Liquid waste has already seeped into the ground at Hanford and created “plumes” or underground pools of contaminants that can join with natural water sources, such as the Columbia River. Part of the effort at Hanford is trying to keep those plumes away from water supplies. In fact, over decades, hundreds of thousands of gallons of high-level radioactive waste has leaked into the environment, particularly at Hanford.

Workers who have been exposed to the radioactive toxins there have reportedly suffered terminal illnesses, like cancer, and even brain damage, according to a report by NBC News. The DOE itself acknowledges on its Hanford Website page that these chemical byproducts are “caustic and extremely hazardous to humans and the environment and couldn’t be poured onto the ground or into the Columbia River.”

Yet somehow, last summer, the DOE announced plans to reclassify high-level radioactive waste in 16 partially emptied tanks at Hanford, Lauren Goldberg, Legal and Program Director of Columbia Riverkeeper, a nonprofit with a mission to protect the Columbia River, told DCReport. If the amendment to the bill to spare Washington State from these reclassification efforts does not pass the Senate, the DOE could relabel waste in another 161 tanks at Hanford or dump it in the ground, Goldberg said. “The Trump administration’s short-sighted plan comes at the cost of people’s health and livelihoods,” she said.“We’re not talking about cutting corners to save money on a skyscraper. The U.S. government’s actions made Hanford the most contaminated site in the Western Hemisphere and the Columbia is the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest.”

Metric tons of nuclear waste

Across the nation, there are more than 100,000 metric tons of spent nuclear waste, both commercial and defense-related—enough waste to fill a football field 20 meters deep, according to the bipartisan U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Of that total, roughly 14,000 metric tons are from the nuclear weapons program. Existing law requires it to be stored in a long-term, deep geologic containment site as far away from the human biosphere as possible, something that has for various reasons not been established, though it has been Congressionally mandated. All bets had been on the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada, but Nevadans don’t want the site there and the area has a “host of technological failings,” according to Geoff Fettus, senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). So, reactor-site owners have mostly kept the spent fuel at their various sites.

“It will be shallow abandonment of the most toxic, long-lasting waste in the world under a layer of grout in leaking tanks directly adjacent to one of the world’s most important and iconic rivers – the Columbia River that divides Oregon and Washington,” Fettus told DCReport, of the plans to reclassify waste specifically at Hanford. “What the DOE has done with this rule is unilaterally, with no oversight from an independent regulator, given itself the authority to decide – at any time and in any way it chooses — how it will make final disposition of this waste.”

Reinterpreting radioactivity

It is unclear exactly which current high-level radioactive waste and how much of it the agency plans to reclassify. But many don’t trust the DOE to conduct the necessary scientific analyses to ensure environmental safety.

“In principle, developing a technically based approach for classifying these wastes is not a bad idea. And DOE would require a technical analysis of the safety of any disposal strategy for the reclassified wastes,” Edwin Lyman, Senior Scientist and Acting Director, Nuclear Safety Project of Union of Concerned Scientists, told DCReport.“But the problem is that those analyses can be complex and uncertainand could leave plenty of room for DOE to manipulate the results” for its cost-cutting goals.

A consortium of environmental and nuclear safety agencies thinks reclassifying material by hazard level instead of the source is a lethal idea. The group of agencies, including NRDC, the Institute for Policy Studies, the Nuclear Information and Resource Service, Columbia Riverkeeper and SRS Watch, wrote a letter to Theresa Kliczewskian Environmental Protection Specialist at the DOE in January, arguing against the reclassification of “extraordinarily radioactive waste.” The letter stated, “Reprocessing waste is categorically treated as HLWand defined by its origin because it is necessarily both ‘intensely radioactive and long-lived.’” To be clear, some plutonium isotopes would take about 240,000 years before decaying away, and some uranium isotopes would stay radioactive for about 4.5 billion years, according to the letter filed by the consortium.

Calls to the DOE for comment were not returned.

Nuclear waste tank farms

One current process of storing waste, vitrification, which converts liquified waste to a glass-like substance-using glass-forming chemicals in a furnace to form molten glass and then pouring it into stainless-steel canisters, is already problematic because the canisters are not placed in a deep geologic repository, but rather stored underground at reactor sites, or tank farms. And disposal of high-level waste in surface disposal facilities used for low-level nuclear waste would lead to threats to ground water at these facilities, Tom Clements, director of Savannah River Site Watch, a research and advocacy nonprofit, told DCReport.Clements has worked for various organizations including Greenpeace International and the Nuclear Control Institute on nuclear issues.

Clements believes the DOE is trying to avoid the cost and effort of building a third nuclear-waste containment site for the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, noting that the agency has stated it wants to reclassify 10,000 gallons of high-level liquid waste as low-level waste. “The biggest concerns at SRS are if canisters of vitrified high-level waste– over 4,000 such canisters have been filled during the process of emptying HLW tanks at SRS – are reclassified as TRU [Transuranic]or low-level waste and dumped off-site,” Clements said. Transuranic waste is typically comprised of tools, rags, protective clothing, sludges and soils that have been contaminated with radioactive waste, mostly plutonium.

Clements also said disposal of vitrified waste canisters from SRS in any other way than handling it as high-level waste neither speeds up the removal of the waste from the tanks, nor speeds up the tank closures, so clean-up time would be unaffected. All it would do is remove safety regulations for handling this deadliest of material.

“Legitimate low-level waste, while far from benign and still very radioactive, does not require the same care in disposal. This nuclear waste is some of the most dangerous stuff on Earth. Millions of people live downstream of these sites,” NRDC’s Fettus said. “Given the mishaps we have seen at the Hanford site in Washington and at other DOE sites, we know that simply abandoning this waste under a layer of grout and hoping for the best is hugely irresponsible and, frankly, a moral failing to clean up the mess we made in the Cold War. This waste is a long-term danger like few others. Quite simply, we cannot afford to mishandle it.”

Before the DOE can unilaterally alter the handling of high-level waste, it is likely to be mired down in litigation, as have past attempts to change the handling of radioactive waste or stopped by Congress. Either way, it stalls a permanent solution for the handling of such toxic material.

Shares