Last month the U.S. Supreme Court handed state legislators a blank check to gerrymander themselves whatever partisan advantage they might like during the 2021 redistricting cycle. After living under the thumb of brutal Republican gerrymanders for the last decade, some Democrats sound ready and eager to cash in where they can.

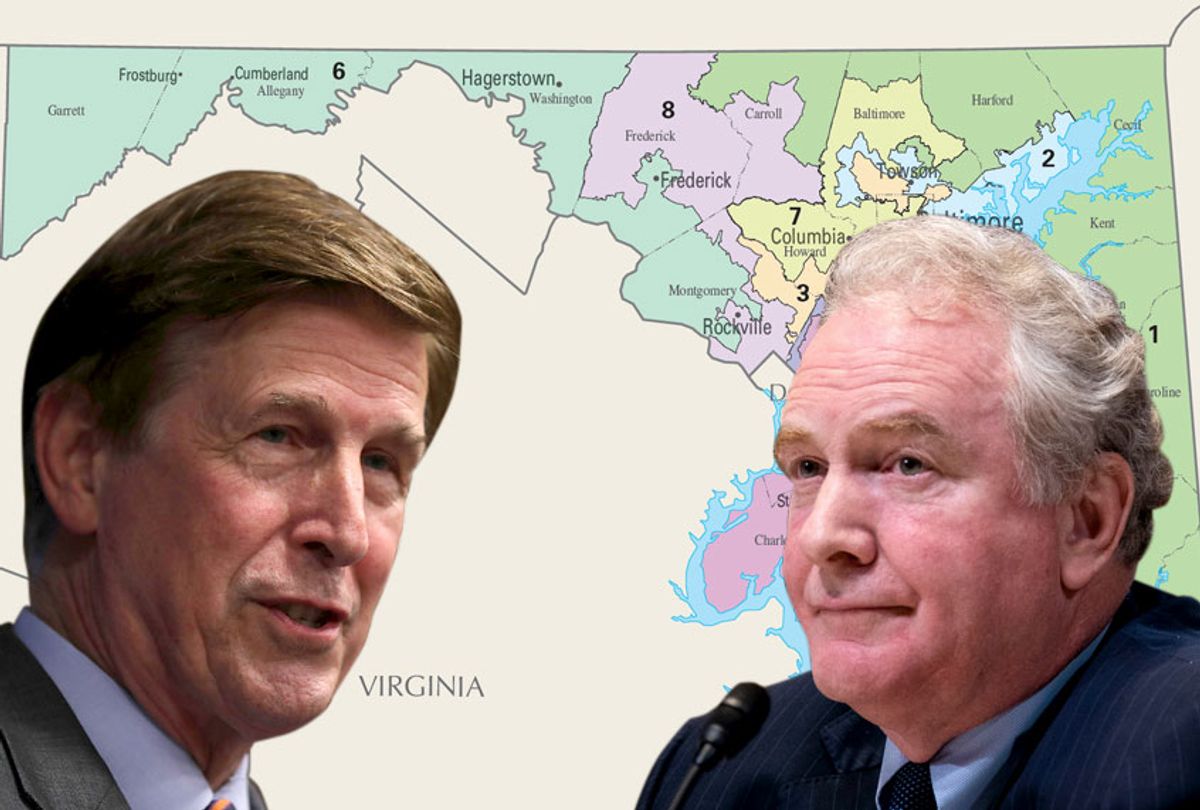

“I don’t see how there’s any other options,” said Rep. John Yarmuth, the last remaining Kentucky Democrat whose seat would be a certain target of GOP mapmakers. He told the Daily Beast that because Republicans will do whatever they can, he “wouldn’t blame any state Democratic legislature for taking full advantage of it.” Sen. Chris Van Hollen, the Maryland Democrat who once chaired the party’s congressional campaign committee, applied the language of nuclear war to mapmaking, declaring that he doesn’t believe in “unilateral disarmament.”

Yarmuth and Van Hollen can talk as tough as they’d like, but the numbers aren’t on their side. Reality is tougher: Democrats have next to nothing to gain from enacting extreme gerrymanders of their own. They have much to lose: After spending much of this decade campaigning against GOP gerrymanders and working to expand voting rights, Democrats shouldn’t abandon their claims to the nonpartisan high ground.

It would be bad policy, but even worse math. Even if Democrats understandably value revenge over moral purity, it’s hard to see how and where that path leads to a majority.

Right now, Democrats control 18 state legislatures nationwide. Six of those states — California, Colorado, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York and Washington — will use some variety of independent commissions to draw congressional lines in 2021. Two others, Delaware and Vermont, have only one U.S. House member, elected statewide. There’s no district to redraw. Democrats control both already.

In six states — Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico and Rhode Island — Democrats already hold every U.S. House seat. They could potentially strengthen those lines, but have nothing to gain.

Democrats control the legislatures in Maryland, Nevada and Oregon, but each of those states are already down to just one GOP House member. It’s certainly possible that Democrats could engineer districts in those states with surgical precision and attempt to shoot the moon. But any move that aggressive also risks spreading Democratic voters so thinly it might actually could jeopardize incumbents. Elected officials don’t like that. In Maryland, for example, Democratic strategists considered crafting an 8-0 map in 2011, before settling on a safer 7-1 split when the delegation balked.

That leaves only Illinois. Democrats seemed to squeeze every bit of advantage out of this state in 2011 when they carved Chicago up with a pizza slicer, maximizing gains by spreading the urban core across as many seats as possible. The party now holds 13 of 18 seats in the Land of Lincoln; it would be challenging, though hardly impossible with today’s technology, to use a pasta maker in 2021 and draw spaghetti-spiral lines south from Chicago and go for the 16th or 18th district. But nabbing an extra seat in Illinois might also imperil racial minority representation, and spread Democratic voters so thin that the party loses many more seats in a future Republican wave election.

There could be pick-ups in 2019 and 2020. Some Democrats imagine they could take control of Virginia (where courts unwound a racial gerrymander and mandated fairer maps) and Minnesota. Virginia’s the richest target, but given the tumult in its executive branch, voters aren’t certain to give the party unilateral control of state government. An aggressive gerrymander there would also come with the cost of scuttling productive reform efforts already underway. Minnesota, meanwhile, has four legitimate swing districts among the state’s eight House members; they’re currently evenly divided between the two parties.

Arizona, Iowa and Michigan could be in play for Democrats, but all are commission states. (Republicans in Iowa and Arizona have threatened to unwind those commissions, but haven’t yet succeeded.)

Pennsylvania or Texas? The GOP’s edge in Texas’ statehouse is down to a tantalizing single digit. The blue wave lifted Democrats to gains in both Pennsylvania chambers in 2018, but nothing even close to control. Those are two fights worth the effort and crucial for progressive policy, but both are extraordinarily heavy lifts.

So what to do? From a purely partisan perspective, there’s no easy road.

Democrats must continue fighting hard to flip state legislative chambers and earn back a seat at the table wherever possible. That’s not easy ahead of 2021, considering how stoutly those GOP-drawn maps have stood for the last decade in Ohio, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

State courts remain open to partisan gerrymandering claims and may prove more persuadable than the U.S. Supreme Court; a state action won Pennsylvania voters a new congressional map in 2018, which immediately produced a more balanced and representative delegation.

Ballot initiatives remain viable in Oklahoma and Arkansas, but Republicans in Florida, Missouri and Utah have worked to unwind victorious 2018 initiatives, suggesting that’s no silver bullet. Active reform movements have channeled public outrage in North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Virginia. Democrats should insist that any serious presidential candidate has a plan to reform and reimagine the Supreme Court, allowing for the potential of someday revisiting this question.

These are urgent tasks. Our politics, especially states suffering from the most extreme partisan gerrymanders, have become dangerously undemocratic, and the 2021 redistricting cycle could cement these anti-majoritarian politics into our system for another decade.

But there’s another problem, and this would be a good time for reformers to broaden their ambition and think outside the zero-sum partisan game. Single-member, winner-takes-all districts will always be inherently unfair — but even more so in this highly partisan era grounded in imbalanced geographic divisions. They can lock large political minorities — and as we have seen, majorities of voters gerrymandered into minority status — completely out of power. They lead to skewed representation, and contribute to dysfunctional politics.

If we want to cure our redistricting problem, we should start by taking on districting itself.

Congress could simply pass the Fair Representation Act, as proposed by Rep. Don Beyer, a Virginia Democrat. Beyer would replace our winner-takes-all system with a fairer system that would allow every vote to matter and everyone to win their fair share of seats. It calls for ranked-choice voting to elect House members, combined with moderately larger districts of three, four or five representatives along the lines of ones used widely in state and local elections. Larger districts, drawn by independent commissions, would be nearly impossible to gerrymander. The lines would simply matter less. A more proportional system would open the door to centrists, independents, minority representation, even third parties. These two reforms, taken together, would not only dramatically transform our politics, but ensure that all sides win only the seats they deserve in every single state.

Republicans might win in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Democrats could pick up seats in Tennessee and Oklahoma. As a result, both parties — if their believe that their policies and candidates have genuine support — might see the wisdom in big-picture reform rather than fighting to hold onto what they have, damaging competitive elections in the process.

Doing the right thing for voters just may be the smartest path for both partisans and those who want Congress to operate as our constitutional framers intended. The Supreme Court’s ruling was a major blow to anyone who believes in fair elections and the importance of making every vote count. The courts aren’t going to save us. It will take creative, bold thinking to reinvent democracy now.

Shares