“Ali, Coach Nazir was asking about you again,” said my friend Jamal with a worried look on his face.

I listened intently, a pit forming in my stomach. “Rumor has it they want to pick you up this week.”

I had heard such rumors before. In fact, I had been living with such rumors for the past two years. Jamal was speaking about the notorious child molester who lived in our neighborhood. I didn’t know which was worse, living with the fear of being violated by Nazir and his gang or the actual act itself. I was fifteen. Making the situation even worse was the fact that I couldn’t even speak about this with Ammi and Abboo my parents. Years ago, when I was about eight, my mother had found an adult cook trying to abuse me. Instead of turning on the cook, she had beaten me with a broomstick!

Such had been my life growing up in Karachi, Pakistan, in a devout Muslim home. My father was an extremely passive man who handled conflict by simply ignoring me for weeks. My mother was engrossed in religion and felt giving me any kind of compliment would encourage pridefulness. I was an only child. The one thing going for me was that we were wealthy. My father’s company paid for the country club, the car, the home, the chef, two maids, and a gardener. Aside from always having to avoid being molested by adult men, it was a great existence. Abboo had promised me that he was going to send me to America someday. I could not wait — somehow, I knew that a better life existed for me there. Of course, it was the 1980s and all I knew about America was from either reading “Archie” comics or watching soaps like “Dallas.”

A few years before I took the flight to Texas, I learned some shocking facts about my birth. We’d experienced an awful tragedy in our family — my Uncle Imran, to whom I was very close, had been killed in a motorbike accident. A month after his death, one of my buddies dropped a bomb on me by disclosing a well-kept family secret — Ammi and Abboo were not my birth parents and my now-deceased uncle had, in fact, been my birth father. Additionally, I learned my birth mother had died giving birth to me. This secret had been kept from me for fifteen years by my parents, apparently having never found an opportune time to tell me.

In some strange dysfunctional way, these traumatic experiences growing up in Pakistan played a role in preparing me as I poured myself into getting ready to travel to the USA — I had developed resiliency to both attacks on my body and spirit as well as a realization that things are not always as they appear. Change can often be just around the corner. And what one thinks of as “truth” may not be the whole truth or even far from it.

Landing in Texas at the age of 18 was the ultimate wake-up call for me. It had taken me over thirty hours to get there, and it changed my world completely. One moment I was rich. Now I was poor. One moment, I could scan the scoreboard on any TV screen and know instantly whether my team was winning or losing the cricket, squash, or field hockey match. Now, American-style football was the only game in town. One moment I was tall, dark and handsome (or so I believed). Now I was only dark. I had gone from being normal to being diverse.

Prior to arriving in the States,I had never written a check, paid rent, purchased groceries, or done laundry. Going from that to sweeping floors at McDonald’s in my first month was quite the culture shock. I remember two attractive coeds from my poli-sci class at the University of Texas pulling up to the store. I dashed into the restroom to give it a good cleaning behind the locked door. In Pakistan, people serving customers behind the counter never mingle with those ordering the food. It’s the land of the haves and the have-nots.

The American collegiate system offers much to its constituents. On one hand, you have an incredible opportunity to gain knowledge, experience, and adapt to life in the U.S. With a good measure of discipline, commitment, and a support system, a diligent student can achieve an awful lot. On the flip-side, as I learned, students in American universities can overdose on freedom, creating social and financial challenges that can easily overwhelm a foreign-born (and even more than a few native-born) young people. Unable to manage life without any guard rails, things quickly took a turn for the worse — falling grades, rising debt, underage drinking and a dysfunctional relationship with my first girlfriend who tried to commit suicide (twice) all sent me into a depression. I felt like I was watching my entire life circling the drain. It had been barely a year since I landed on American soil, yet in so many ways, I felt I had aged a decade. The “Land of Opportunity” had quickly become the land of consequences. One such consequence was a hospital visit after I slashed my wrist. This was not the American college experience I had dreamed of.

Something kicked in at this low point. Call it my adversity quotient, a term used by author Paul Stolz to refer to one’s capacity to endure hardships. Somehow, I found myself drawing upon the resilience developed years ago when dealing with the threat of sexual assault. Facing deportation and bringing shame to my family also served as valuable fuel. I needed a fresh start. I switched schools from the larger university to a community college. The college’s intimate class size made it harder to hide. At the urging of my professors, I got my first leadership opportunity as the International Student Club leader. I loved organizing events and having other students enjoy these and look up to me created a sense of responsibility for others. I liked how that felt, that sense of belonging. I also enrolled in remedial classes to improve my grades. Here I ran into Dr. Bill Bradley, my first mentor. He was the only highly-educated person who had ever taken an interest in me. I aced his class.

There is something motivating about fresh starts and seeing those green shoots of success. That’s something you can build on. I found a job at a new McDonald’s. I was amazed at how my store manager had started his career there “on the grill” (an entry-level person). My regional manager who oversaw eight stores had started on the front register, just as I had. I was in awe of the system McDonald’s had created to allow rookies to make their way to the top. I saw a path before me and my confidence began to rise. Nine months later, I was promoted to shift-manager and given a raise.

Back in the late ‘80s as a struggling young immigrant in the United States, I began to understand that few things worth having come easily. Those who were successful, whether in academia, government, business, or television, paid a price for their success through hard work and perseverance. For the first time, I saw a way out of my troubles. I had hope and a future. In America, it was possible to find success after failure and, although achieving success was not easy, everyone had the opportunity to seek it. This was not like back home where the transition from blue to white-collar was very nearly impossible. America, on the other hand, offered the rare and precious freedom to fail and start over.

Growing up in a Muslim culture in Pakistan, I had been brought up with all kinds of stereotypes about religion in America. Enter Judy Fox — the girl that turned my life upside-down. We met at work and became fast friends. She was an art education major and a strong person of faith. I was drawn to the message of love and grace found in Christianity — very different than the works-based faith I had been raised with. The relationship with Judy led to my own transformative faith journey that eventually led to my conversion. The freedom of religion in America allows us to to search, to choose to believe or not. Such a freedom is rare in the East.

Judy and I were married in 1991. In order to find more income to support my family and finish my last year of an accounting degree, I tried applying my customer service skills at a boutique consulting firm that applied technology to niche tax laws. I fell in love with the business. I was amazed at how in America you could innovate and succeed taking a single product to market if you were good at it. So enamored was I with the freedom of entrepreneurship offered by America that I quickly started my own consulting firm at the age of 23.

Unfortunately, having little cash and even less credibility, my business died. I didn’t give up. I networked and met a local CPA named Ron who exposed me to the world of intrapreneurship — building a business inside his business focused on the same tax ideas. I jumped in with both feet and Ron became my first sponsor. A “sponsor” is different than a mentor — sponsors take greater risks on your behalf and create opportunities for you. Thus began our protégé-sponsor relationship. Ron taught me how to sell. One of the best tools I gained from these lessons was the stylistic adjustments I had to make to adapt to the American way of making sales and doing business. I learned that it was as much about relationships as it was about the technical aspects. For instance, most of Ron’s clients loved to talk about baseball. I learned all about professional baseball and, miraculously, this greatly impacted my sales numbers! The business we started turned profitable.

Under Ron’s sponsorship, I was introduced to an executive at Ernst & Young (EY), a “Big 4” professional services firm. Ron told me to apply and I was hired there in the mid-1990’s. Here again, was a transformation opportunity. I wanted to build a new business for EY, but I had to be patient. I knocked on many partners’ doors. Oftentimes, larger firms like EY have spoken and unspoken social protocols — whether or how staff should be going directly to senior partners to pursue entrepreneurial ideas. Fortunately for me, I was clueless to some of these and that may have worked in my favor. Refreshingly, I learned that partners cared less about my level and more about what I could do for their clients. My career took off. Eight years later, I was promoted to partner having built multiple new tax businesses.

As I look back at my journey from a counterman at McDonald’s to a successful EY partner, the advice I can offer to others is to take advantage of the freedom to fail and start again, to draw upon stored-up courage from past adversity, to be willing to embrace new environments, and to find purpose that can propel you forward. Why are you doing what you are doing? For me, because of my faith, it was playing to an audience of One. For others, it’s their loved ones. Still others are intrinsically driven to be the best.

On 9/11, America bravely faced a dark and horrific day. Being a former Muslim at that painful time was also a sobering experience. In the first few weeks, I lived in fear, avoiding commercial air carriers, opting instead to drive long distances if I had to travel. I monitored stories of people from Muslim countries being beaten up. Overall, though, this was more the exception than the norm and the American people, in my view, did not judge an entire community by the actions of the few. The tragedy of those attacks in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania stirred up the flame of patriotism in me. I wanted to pledge allegiance to the nation that had given me so much. In 2002, I became a proud American citizen.

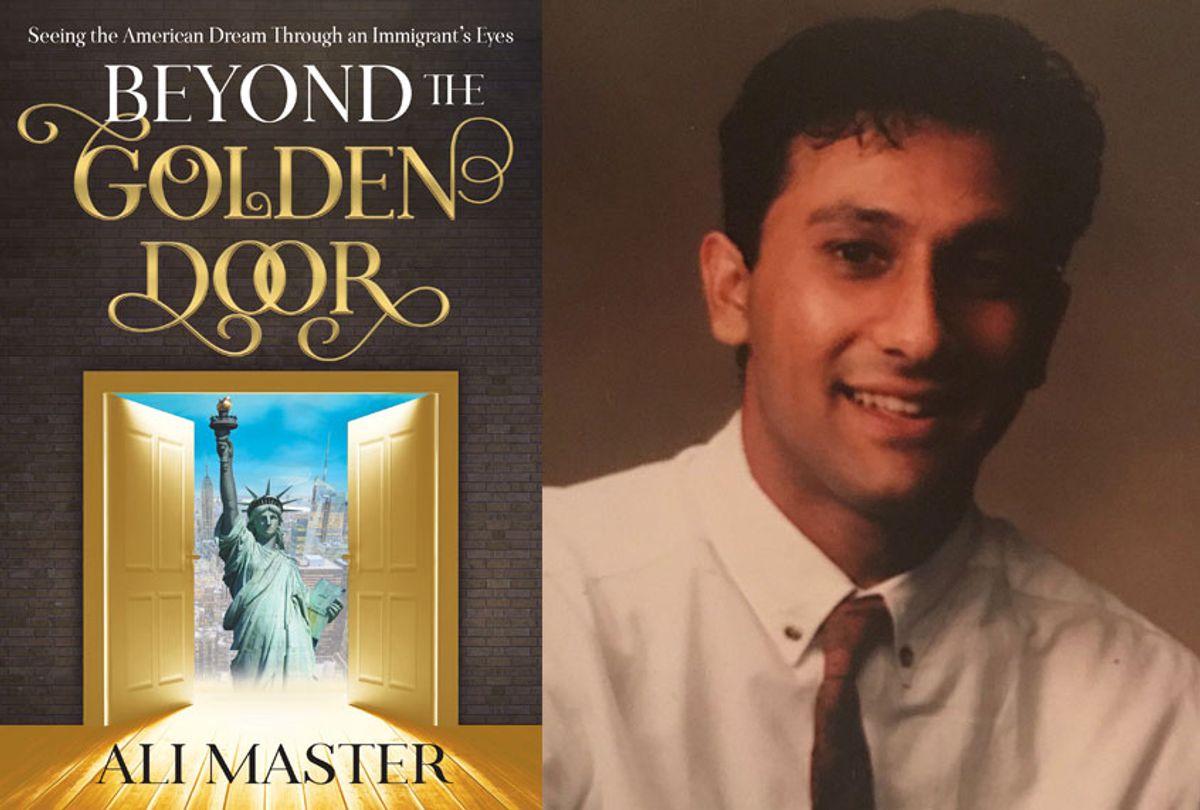

From where I sit today, America is at a crucial crossroads — division is on every corner. In “Beyond the Golden Door,” I am hoping to inspire Americans from all persuasions to unite around our core values -- freedom and dignity for all, justice, and a shot at achieving the American Dream if you are willing to work for it. There are many others like me who can come, find love, faith, innovation, and a new country they can call their own.

Shares