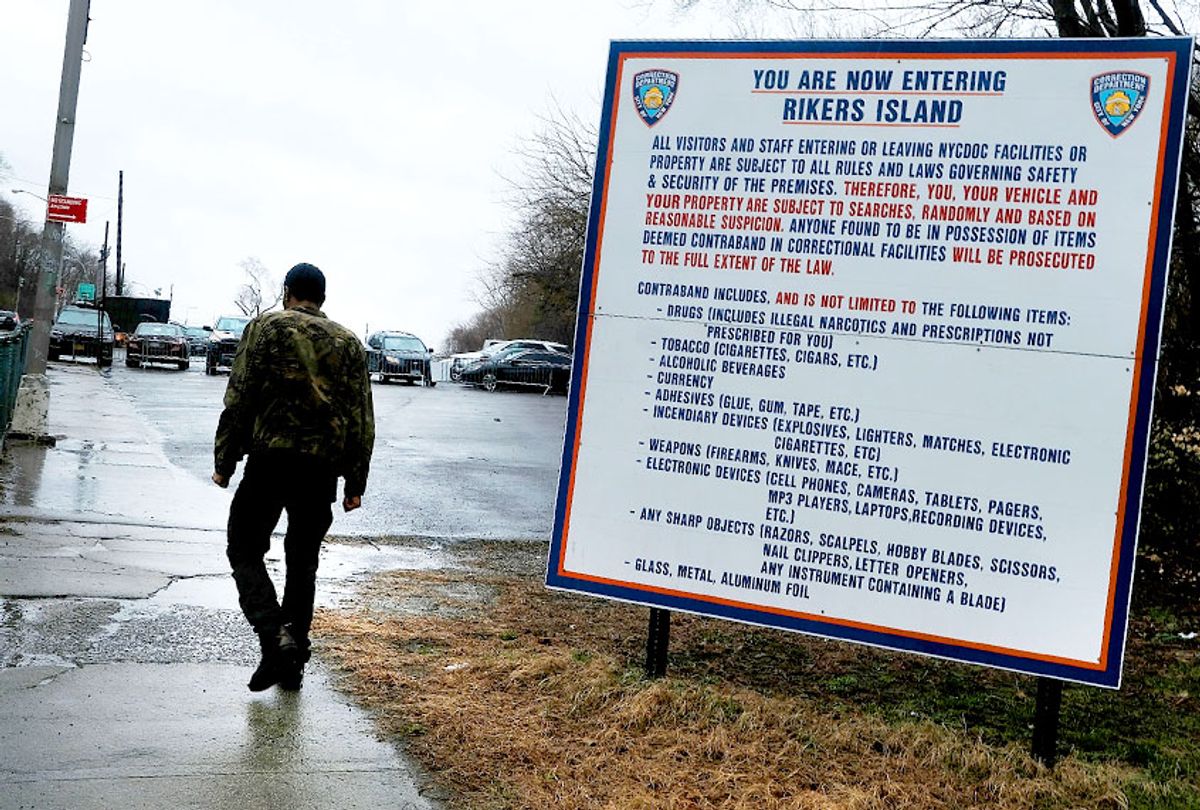

In 17th-century Venice, the bridge that conveyed convicted criminals across the Grand Canal to the cells of the Doge’s prison came to be known as the Bridge of Sighs. Its counterpart here in New York, which spans the East River between Queens and Rikers Island, is referred to by the prisoners and guards who cross it as the Bridge of Pain. Those who’ve never had occasion to make that crossing should count themselves blessed. I wish I could say the same.

A look of mild surprise registered on Judge Joan Carey’s face as she read my pre-sentencing report and discovered I was a Dartmouth graduate. I could understand her bewilderment — the prisoner’s dock in criminal court was the last place I ever thought I’d find myself. Ironically, two decades earlier, when I was a high-school junior on Long Island, I had entered, and won, a Law Day essay contest sponsored by the Suffolk County Bar Association. The Law Day theme that year was inspired by a famous quote from one of Teddy Roosevelt’s speeches to Congress: “No man is above the law, and no man is below it.” A high-minded sentiment I had no trouble defending in my essay, never suspecting there would come a day when Rikers Island would teach me otherwise. But teach me it did, and after doing time in that hellhole I can say for certain that it’s all too possible for a man to wind up “below the law.”

During the crack epidemic of the '80s, the flood of new inmates that inundated Rikers Island fostered a siege mentality among the overworked corrections officers. Faced with an ever-increasing inmate population and the city’s persistent failure to heed their calls for reinforcement, the C.O.s were as angry about the overcrowding at Rikers as the prisoners were. The difference was, the C.O.s had batons and a ready supply of inmates on which to vent their anger — and as I quickly discovered, they took full advantage of every opportunity.

When I arrived at Rikers, I was held in a bullpen cell in the intake unit for 26 hours, crammed into a 10'x12' space with so many inmates there was barely room to stand, much less sit down. The clogged commode in the cell had no lid, and it was overflowing with vomit and excrement, but when anyone complained about the stink, the C.O.s on duty would just shout back, “Handle it!”

Inevitably, with so many prisoners crammed into such tight quarters, tempers flared, and whenever a fight broke out, the C.O. at the fingerprint station would blast his whistle, and then the flying squad would come running in with riot shields and batons to drag the combatants out of the bullpen and off to a private cell down the hall for a “beat down.” These beatings were never conducted in sight of the bullpen prisoners, but the screams and moans of the unlucky victims were clearly audible and provided a grim preview of the brutality I’d be facing in the months ahead.

The special squad of guards who conducted random shakedowns in the dormitory cells were especially callous. The first time they tossed our unit for contraband, one of the Latino inmates cursed them out for throwing a framed picture of his wife and kids face-down on the floor. The C.O. he yelled at responded by grinding the photo beneath his heel before laying into the inmate with his baton. The beat-down left the inmate with several cracked ribs, and when it was over, he pleaded to be taken to the infirmary. But the C.O.s told him if he insisted on seeking medical treatment, he’d be charged with assaulting an officer and transferred to solitary confinement. Cowed by their threats, the inmate decided he could “handle it,” and when he kept the whole dorm awake that night with his groaning, none of us raised a word of complaint. Thirty-four years later, I can still hear him groaning. Like Kurt Vonnegut said, “And so it goes.”

When people say, “Don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time,” I don’t disagree. If you’re convicted of breaking the law, you should expect to be punished. However, I believe society’s demands for justice should be considered fully satisfied by a prisoner’s forfeiture of his freedom. Sadly — and to the city’s shame — the chronic overcrowding and substandard facilities at Rikers have for many decades forced its prisoners to forfeit their Constitutional right to humane treatment as well, and that’s an unconscionable perversion of justice that has stained the city’s good name for far too long. Which is why I welcomed Mayor Di Blasio’s 2017 announcement of a ten-year plan to shut Rikers down completely and replace it with smaller, borough-based jail facilities.

So far, the city’s plan has produced some commendable results. In 2018, the average daily population of prisoners at Rikers dipped below 8,000 for the first time in more than 30 years, and the city hopes its efforts to reform the bail system, along with its push for more pretrial diversion programs, will continue to reduce the number of inmates held at Rikers going forward. It’s a start, but there’s still a long way to go.

By the city’s own admission, the plan to shut down Rikers will only be feasible when the daily population drops to 5,000 or less, which would require nearly a 40% reduction from the current numbers. That’s a big ask, and only time will tell if it’s achievable.

But the more immediate challenge the city now faces in Year 3 of the master plan will be finding acceptable sites for the new borough-based jails that need to be built in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx. The site-selection process will no doubt spark much controversy and public debate, but unless it is successfully resolved, the goal of one day ridding the stain of Rikers from the city’s reputation will never be reached.

Maybe, like me, you’ll reach the same conclusion — that a city made famous by the Statue of Liberty shouldn’t also be made infamous by a prison as notoriously inhumane as Rikers Island.

Shares