According to press accounts, all of the Democratic contenders taking the stage this week rank on a spectrum of more or less “liberal.”

They don’t.

While most are liberal, two or three are leftist, not liberal. It’s important that voters start distinguishing between those terms because the primary presents them a stark choice between the two.

Leftism and liberalism are distinct political categories with different histories. Understanding the problem of fusing them requires a quick tour of British history from around 1845 to 1980 with just a few stops along the way to the U.S. in 2019.

Liberalism

I teach my British history students that liberalism as a party platform dates from 1840s England, when a group of politicians proposed a set of ideas very different from their Tory and Whig colleagues.

The Tories were the party of Crown and countryside, while the Whigs tended to favor merchant interests over aristocratic landowners. Neither party fit our notions of “left” or “right.”

By the 1840s, neither fit the needs of industrializing Britain, either, according to the new liberal thinkers. England’s population was booming, while people were leaving the farm for the factory and bitterly poor living conditions in cities. Could industrial capitalism work for everyone, the liberals asked, not just industrialists?

These liberal newcomers, people like Richard Cobden and William Gladstone, seized on ideas like those in Scottish economist Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations” for answers.

For example, they embraced Smith’s idea that industrial wealth could create prosperity beyond just capitalist owners. They figured that when new factories opened, capitalists bought widgets and hired workers to use them. The workers would have spending money, the theory went, and demand new goods. In response, another capitalist would build a factory to provide these consumer goods and factory widgets, in a virtuous cycle.

The idea was that if you got the cycle going fast enough through free trade rules and low taxes — in those days usually raised during wartime, so wars had to be avoided — the value of a worker would go up while the price of goods would go down.

The main role of government for Britain’s new Liberal Party, then, was just keeping the wheels of commerce greased and staying out of the way.

The new Liberals ultimately replaced the Whigs and led the British government off-and-on for the next 70 years, all the way to World War I. More important, their theories about small government were often predominant across party lines.

That changed somewhere around the turn of the 20th century, when a new party, the Labour Party, arose arguing that the Liberals were not willing to do what was needed to help the struggling.

For generations, hands-off liberalism had allowed poverty to persist, said people like Scottish M.P. Kier Hardie. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” tended to hand industrialists big payoffs while handing workers scarcely enough to keep them upright on the factory floor. That left “the poor,” Hardie said, “to struggle for existence unaided by the State.”

The new Labour Party replaced the Liberal Party from roughly the mid 1920s, introducing policies that Americans would today consider “leftist.”

Britain’s Labour Party steadily expanded income taxes from the later 1940s onward, created disability insurance and old age pensions, and after World War II oversaw the creation of the National Health Service, providing free health care for all.

The left

The trend of economic interventionism quickly caught on in the United States. In 1932, Democratic presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt defeated the more liberal Republican Herbert Hoover by promising a massive government stimulus package that would address the Depression’s wreckage: The New Deal.

Broadly speaking, this expansion of government-run social welfare programs, a hallmark of the left, continued through World War II and the next 40 years or so. Even Republicans began to see a larger role for government. Dwight Eisenhower embraced some New Deal policies, expanding Social Security and supporting low-income housing, while Richard Nixon tried to expand federal support for child welfare.

The anti-left backlash came in the late 1970s. Proponents of a return to economic liberalism included University of Chicago economists Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

By 1980, President Ronald Reagan was arguing for unfettered capitalism. He wanted to unleash the “magic of the market.” In this, Reagan was following Adam Smith’s belief in an invisible hand, the supposedly natural power of market demands to sort out the economy and, implicitly, society.

Reagan — like his British counterpart Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher — reduced taxes on the wealthy, fought unions, shrunk the social safety net and privatized national utilities and industries.

This return to liberal ideas, generally called “neoliberalism,” crossed party lines in the late 20th century, with U.S. President Bill Clinton’s “New Democrats” and U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s “New Labour” adopting them beginning in the mid-1990s.

Sensing voters approved of Reagan’s liberal policies, Clinton, a Democrat, campaigned on reducing welfare and completed George H.W. Bush’s North American Free Trade Agreement.

Britain’s Tony Blair, meanwhile, dragged the formerly leftist Labour Party toward the liberal, campaigned to “modernize” in his words, the U.K.’s welfare system.

“I believe Margaret Thatcher’s emphasis on enterprise was right,” he said in 1996. “[P]eople don’t want an overbearing state.”

Liberals and the left now

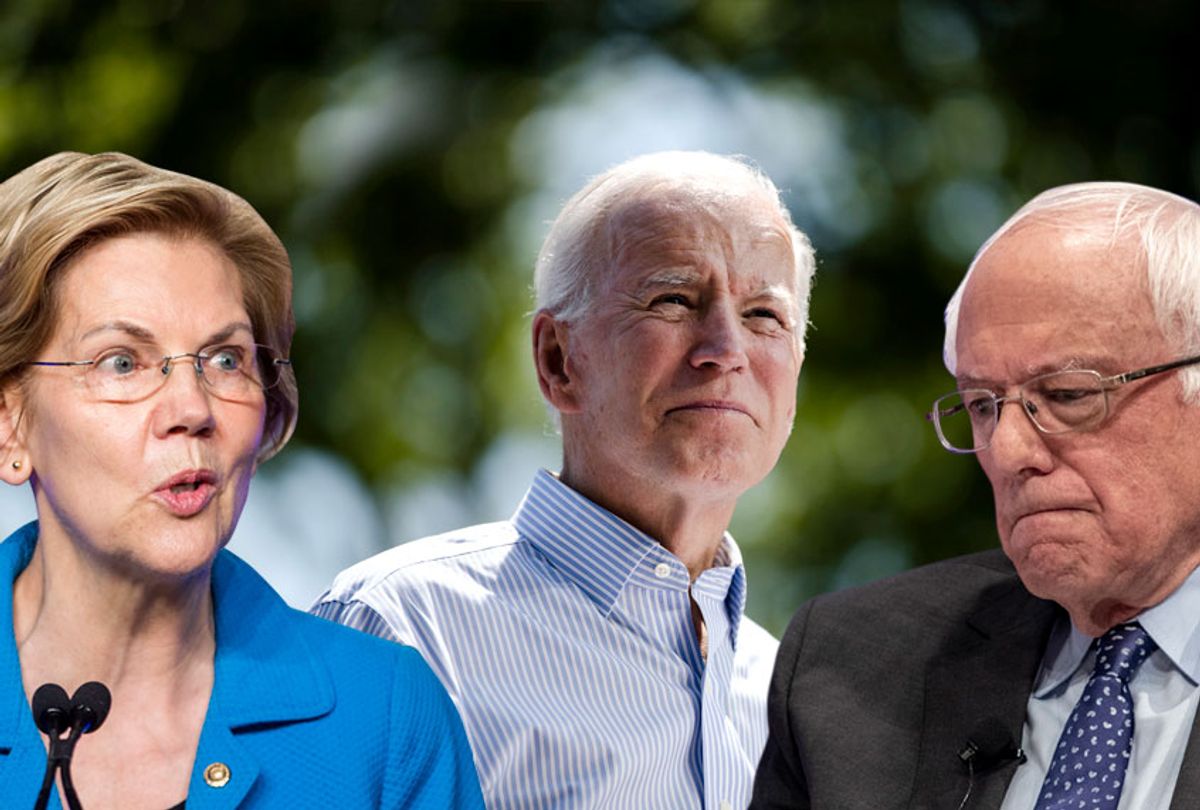

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden is squarely liberal in the mode of the Clintons. He was a supporter of NAFTA and championed the market-based Affordable Care Act over universal health care.

Other major contenders remain a bit of a mystery on where they stand on the liberal-left divide. Some observers thought Kamala Harris avoided tipping her hat in her recent biography; while Pete Buttigieg is also hard to pin down.

Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are left-leaning. They’re both in favor of a national health insurance, and call for an end to private health insurance to make the system work. They’re both for tax changes that would take more income from the wealthy in order to bolster Social Security and other welfare. They’re both for greater regulations on the banking and lending industry and the creation of post office banking.

Voters need to understand the fundamental differences between liberalism and leftism. It’s the difference between a candidate who believes capitalism, with just a little refereeing, will eventually provide what working people need, versus a candidate who believes serious intervention in the capitalist economy is necessary.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

John Broich, Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University

Shares