It's August and the end of summer reading season is near, but there are still plenty of daylight hours left to lounge outside — or cool off indoors, away from the heat — with a good story. Here are four novels and one collection of linked short stories hitting the bookshelves this month that you won't want to miss.

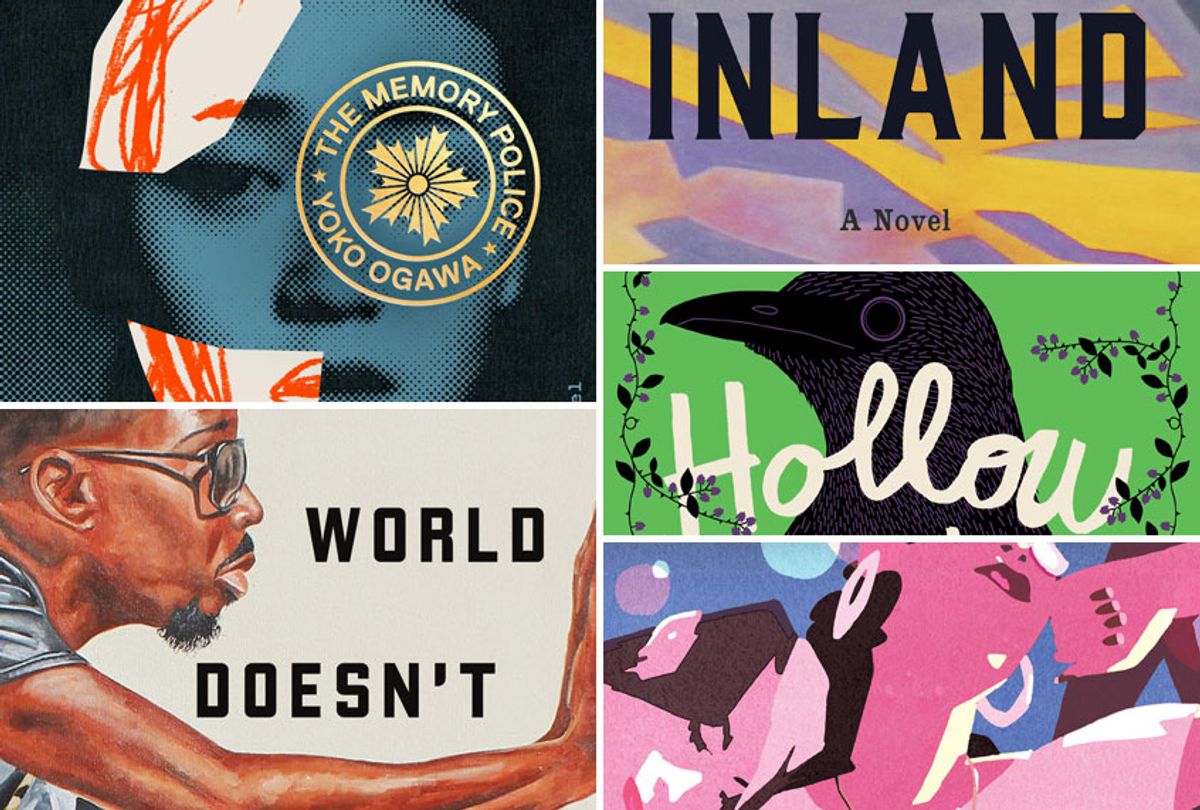

“They Could Have Named Her Anything,” by Stephanie Jimenez (Little A, August 1)

On the surface, Rachelle “Rocky” Albrecht is just another of the wealthy majority at Bell Seminary, but she uses her wealth to try to distance herself from her preppy peers. She is white, rebellious (coming to class with a pack of cigarettes and slapping a Planned Parenthood sticker on her laptop) and uses money to “circumvent the rules.”

Meanwhile, Maria Anís Rosario feels nothing like her peers — a Latinx scholarship student from Queens whose mother cleans houses and whose father just lost his job. As her family struggles to make ends meet, they don’t have the capacity to seriously entertain her dreams of attending college.

Maria is essentially “adopted” by Rocky after she develops a friend crush on her. At first, Maria is thankful for Rocky’s over-the-top generosity, but is soon disheartened by her friend’s casual cruelty and racism. Rocky, meanwhile, longs to have a close-knit family like Maria’s, as she’s basically been abandoned by her feuding parents.

The closer the girls become, the more jealous they become of each other, until things implode on an ill-fated trip to Las Vegas. Jimenez’s insightful, pulsing novel succeeds in its relatability, nailing that sweet spot between teen and adult fiction. — Ashlie D. Stevens

"Hollow Kingdom" by Kira Jane Buxton (Grand Central Publishing, August 6)

Soon S.T. learns that whatever afflicts Big Jim has also infected all of the humans — MoFos, as he's learned to call them — he encounters and turned them into the drooling, violent undead. Being a resourceful crow, he teams up with Dennis, Big Jim's bloodhound with "the IQ of a dead possum," to head out into the uncertain violent new world to try to find a cure for his best friend.

Big Jim has taught S.T. how to look out for numero uno, how to tell the passage of time by a calendar of big-breasted Germans, and how to turn on an iPhone. TV has taught him everything else he knows about humanity, and as a result he identifies more with humans than his own species, and the rise of the animal world over the MoFos sends S.T. spiraling into an identity crisis: Is he crow or MoFo?

Through battles bloody and existential, S.T. has to keep Dennis safe, follow the clues doled out on the natural world's versions of the Internet, and form alliances with those he once spurned in order to keep his ragtag murder intact and just maybe save civilization, or what's left of it, before the apex predators — and some creepy new interlopers — slaughter all the remaining innocents in an epic battle for territory. It turns out Big Jim taught him some other things, too, like the power of loyalty and how hope, even the tiniest, wrinkliest sliver, can power us through our darkest hours. — Erin Keane

“Inland,” by Téa Obreht (Random House, August 13)

She’s kept company by her youngest son, her husband’s 17-year-old clairvoyant cousin, and Evelyn, her daughter who died of heatstroke as a baby, but is growing up in her mother’s mind.

Then, there is Lurie, a young man who was orphaned and left homeless at the age of six. He survived by working for the Coachman — sleeping in his stable and helping him collect valuables off “lodgers who'd passed in their sleep, or had their throats cut by bunkmates.” Lurie grew into an outlaw on the run, haunted by ghosts from his early childhood. He spends much of his alone time conversing with Burke, a camel that was part of the United States Camel Corps (a nearly-forgotten initiative — one I hadn’t heard of until this book — by the US Army to use camels as pack animals in the Southwestern United States).

Obreht, who is best known for her stunning debut novel “The Tiger’s Wife,” has a knack for illuminating both history and human nature in her writing; “Inland” continues in that vein. The characters’ stories culminate in a six-page final chapter that is a grim, quiet metaphor for our struggles in and against the “the uncertain and frightening textures of the world.” — ADS

"The Memory Police," by Yoko Ogawa (Pantheon Books, August 18)

Set on a mysterious island off the coast of an unnamed country, a young woman who works unremarkably as a novelist — "Few people here have any need for novels," she admits — can't hold onto the memory of things as they are systematically "disappeared" by the sinister local government. She's not alone; rather, those who do remember are the outliers, and dangerously so.The act of disappearance is brutal in its simplicity: First every instance of a thing vanishes — birds, or roses, or hats — and along with it, all memory that it ever existed begins to fade immediately, with the psychic banishment strictly enforced by the secretive and brutal Memory Police.

Ogawa draws clear parallels to Orwell's "1984" here: the truth of human experience can be forced into whatever shape an oppressive government dictates, with the threat of complete oblivion always on the horizon. Resistance means imprisonment, or worse.

When the novelist learns her beloved editor is one who retains memories, she conspires with an old friend of the family to hide him in a crawl space in her house, where the intimacy of their shared secret binds them further together. From there Ogawa's story develops into a taut, claustrophobic thriller; the police grow more suspicious of civilians and the disappearances grow more frequent and disruptive around them as the writer races to finish the book within the book, which turns and deepens into darker territory along with the story wrapped around it. — EK

"The World Doesn't Require You" by Rion Amilcar Scott (Liveright, August 20)

In "The World Doesn't Require You" Scott's cast of Cross River citizens — including the musical pioneer son of God and the acolytes he later cultivates, a crime-world underling, a PhD student with a nihilistic streak, a tragic robot servant, and Underground Railroad re-enactors — grapple, in interlinked tales across a century, with existential restlessness and the push-and-pull tension between individualism and community in a town founded on surviving unspeakable terror, brimming with innovation, and bordered by possibly haunted Wildlands, woe-infused waters and the white town of Port Yooga.

Scott anchors this collection with a searing novella, "Special Topics in Loneliness Studies" that lays bare the malevolent absurdities of academia through the entangled deterioration of two professors at local Freedman's University who are both obsessed with Cross River mythology, for different reasons and to separate ends. — EK

Shares