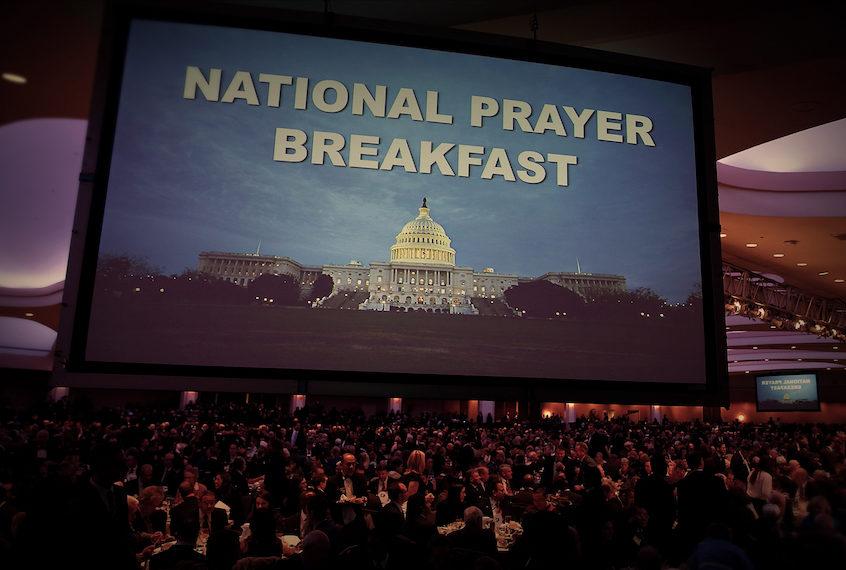

In July 2018, the Justice Department unsealed a criminal complaint that detailed how a woman from Russia, Maria Butina, was accused of “acting as an agent of a foreign government” by attempting “to establish a back channel of communication” with powerful politicians, most notably at the 2016 and 2017 National Prayer Breakfasts. She would go on to plead guilty of conspiring as a clandestine foreign agent on behalf of the Russian government.

Days after the document became public, The New York Times released a story, “At Prayer Breakfast, Guests Seek Access to a Different Higher Power” which detailed how the National Prayer Breakfast — an event that, in most peoples’ minds, isn’t synonymous with international political strategy — had increasingly become a ticketed, “pay-to-play” event for foreign lobbyists.

Behind it all, is a secretive Christian organization known publicly as the Fellowship Foundation. A new Netflix series called “The Family,” which is how the group is known internally, takes a deep-dive into their inner workings and the extent of their political influence.

The series is directed by documentary filmmaker Jesse Moss, and based, in large part, on the 2008 book,“The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power,” by Jeff Sharlet, who lived with and eventually wrote about the group.

As Sharlet wrote about in his 2003 Harper’s article “Jesus Plus Nothing” — a term the group uses to describe their nondenominational Evangelical theology — The Family was founded in April 1935 by Abraham Vereide, a Norwegian immigrant who made his living as a traveling preacher.

“One night, while lying in bed fretting about socialists, Wobblies, and a Swedish Communist who, he was sure, planned to bring Seattle under the control of Moscow, Vereide received a visitation: a voice, and a light in the dark, bright and blinding,” Sharlet wrote. “The next day he met a friend, a wealthy businessman and former major, and the two men agreed upon a spiritual plan.”

Vereide and his friend enlisted 19 business executives to join them for a weekly breakfast meeting, where they would pray that Jesus would redeem Seattle and squelch the city’s radical unions. Together, they asked God to raise up a leader among them.

Sharlet wrote: “One of their number, a city councilman named Arthur Langlie, stood and said, ‘I am ready to let God use me.’ Langlie was made first mayor and later governor, backed in both campaigns by money and muscle from his prayer-breakfast friends, whose number had rapidly multiplied.”

Where some recent Netflix documentaries, like “Abducted In Plain Sight,” have you teetering between shock, disbelief and, at times, disgust at a rapid rate, “The Family” is definitely a slow-burn — but it almost has to be. Watching the docuseries is like watching a dark “Forrest Gump”; throughout major political maneuvers in our country’s recent history, it’s almost guaranteed that a representative from the Fellowship Foundation was there.

This is where the five-part series excels. Despite some dramatizations that look like they would be more appropriate in a brooding Lifetime flick, “The Family” weaves together a series of seemingly disparate public events, and shows how the religious group was involved. There’s former South Carolina governor Mark Sanford’s extramarital affair and bizarre disappearance; a petition by clergy to strip a boarding house in Washington, D.C. of its tax-exempt status; political dealings with authoritarian governments; a trip by conservative Alabama Rep. Robert Aderholt to Romania to campaign for anti-LGBTQ rights and advocate for Christian policy.

Throughout the series, we do hear from past and current members of the Family, who explain that the organization’s perceived secrecy is inherited from longtime leader Doug Coe; once described by Time as the “stealth Billy Graham,” Coe often said that he wanted the work of the Family to point to Jesus, not to man, so any politician’s public affiliation with the group was something of a liability to its mission.

That’s something they’re reportedly moving to change. According to an interview with Rolling Stone, filmmaker Jesse Moss says the Family wants to “adapt to the 21st century with a greater degree of transparency, though only time will tell if that’s true.”

But in watching the “The Family,” it becomes increasingly apparent just how apt that the series’ logo is: an illustration of the White House supported by a hidden tangle of overlapping roots, a visual metaphor for how simultaneously wide-reaching and deeply-enmeshed the Family’s influence is in American political life.

A guiding principle of the organization is the New Testament commandment to “disciple every area of the world,” and for the Family, this isn’t just a mission-minded imperative, but rather a call to become involved in various stations of power in America. A document found by series producers shows that the group sought to connect with, among others, “financiers and industrialists, congressmen, television industry, news industry, state governments, seminaries and churches, junior executives.”

While the viewer will has the job of parsing through a vaguely conspiratorial tone at certain points of “The Family,” the series presents a highly compelling case for scrutinizing the degree to which state and church are really separated in our country.