Two authors from Northern Ireland are set to light up U.S. bestseller lists this summer with their latest thrillers.

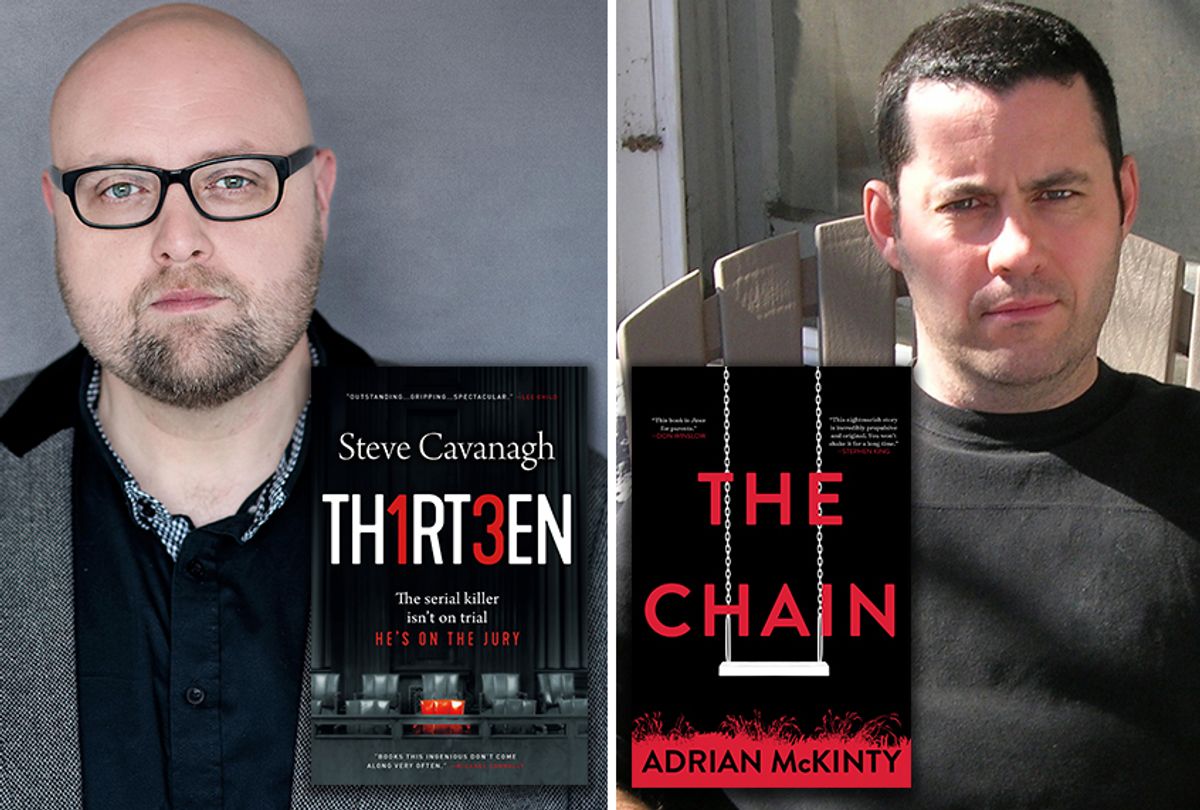

Adrian McKinty was born in Carrickfergus. He is the Edgar Award-winning author of the Sean Duffy series and his new standalone, "The Chain," has been championed by Don Winslow, Stephen King and Tana French. Movie rights have sold for seven-figures to Paramount Pictures and the book is on every list of the best thrillers coming out this summer.

"The Chain" tells the story of Rachel, whose daughter has been kidnapped. In order to get her back, she must pay the ransom — and then steal another child.

Steve Cavanagh was born in Belfast. He is the Crime Writers Association Gold Dagger winning author of the Eddie Flynn novels about a con artist turned trial lawyer.

"Thirteen," the story of a serial killer who works his way onto the jury in a murder trial, is already an international bestseller, has been nominated for multiple awards, and has been praised by Lee Child, Michael Connelly and Ruth Ware.

Here, Adrian and Steve discuss their upbringing, the books that inspire them, and more.

Adrian McKinty: Steve, famously your mother gave you "Silence of the Lambs" at an impressionable age, what other books and writers have been an influence on your career?

Steve Cavanagh: I think I was twelve when my mother gave me that book. Some people balk at the idea of a child of that age reading "Silence Of The Lambs," and I’m glad you didn’t. And I know why. We grew up during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. I was in Belfast, you were in Carrickfergus, and a book about cannibals and serial killers skinning innocent people was a bit of light relief from the reality of that low-level civil war. I wouldn’t give my daughter "Silence Of The Lambs," and she’s twelve right now. We grew up in different times, and I think our generation is desensitized to violence.

In terms of other books and writers that have influenced me — I think we’re subtly influenced by everything — but I think I can point to a handful of writers who I look up to. I try to learn from them and what they’ve accomplished. Michael Connelly is one, Lee Child and John Connolly. Their work made me want to be a writer, and the fact that Lee is from England and John is from Dublin somehow made it easier for me to imagine that I could write American crime fiction. I also think you never stop being influenced. The crime writer Sarah Hillary put me on to Patricia Highsmith recently, and having never read her work I am now devouring it and it has influenced a standalone novel that will be released in the U.S. next year.

What about you? I know James Ellroy is a big influence for your Duffy thrillers, but I wanted to ask about your latest — "The Chain." This is pure suspense, and I think one of the finest thrillers I’ve read. I was delighted to see the reaction from the writing world, and Hollywood. This is rightly recognized by writers like Stephen King as a masterpiece. I wanted you ask you about the the extraordinary story behind the writing of this book, and what authors influenced the writing of this novel? I know on a practical level Don Winslow was hugely inspirational, but this kind of high-concept thriller has to have a fairly different set of literary influences than the Duffy books? And, when you got the quote from Stephen King how did you react?

McKinty: I remember reading Stephen King to my little brother in our bunk beds at night when we were supposed to be asleep. I was about 10 and he would have been 8 and I was reading "The Shining" or "Christine" or "Cujo" to him and I was terrified and he was so scared he would be whimpering. And I asked him if he wanted me to stop and he always said no. And you’re right about the milieu. This would have been on Coronation Road in Carrickfergus which is a Protestant housing estate during in the 1970s and 1980s right in the heart of the Troubles. Many times the police and army came to arrest people on the street for terrorist offenses and of course in our daily lives there was violence and men with guns everywhere.

I am so glad that my daughters have never even seen a gun in real life or seen a body or been involved in a bombing or a riot. I often wonder if our entire generation is growing up with undiagnosed post traumatic stress disorder and writing is my way of coping with it?

James Ellroy, Don Winslow, Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson were the writers whose style influenced me the most. The economy of their writing is breathtaking and something to be emulated (I think). In terms of making me want to be a writer I think it was the book "The Peregrine" by JA Baker — which is kind of my secular Bible. If an ordinary bloke riding his bicycle round Essex could write something like that I thought then anything is possible.

Do you feel that Belfast writers might possibly have an advantage in that from an early-age children are forced to interrogate history and navigate questions of identity as well as coping with all the usual domestic, teen, school dramas etc.?

Cavanagh: See, I’m not sure that we are forced to interrogate history or our identity. I think if you grew up in Northern Ireland between the '70s and the early '90s, your parents, your school and your community were all part of indoctrinating you into that religious, political and historical divide. To some extent this is a class question — kids in the more affluent areas of South Belfast didn’t face that level of indoctrination, but the working class definitely did. I was lucky in that my parents were mixed — Protestant and Catholic, so when school, or church or my little pocket of friends in the community were advocating sectarianism, I was rejecting it. If you questioned identity and history then I think you were one of the lucky ones, but that could also make you an outsider — not really part of any community and that is probably what influenced me in being a writer and turning to crime fiction in particular. I identified with the American private detective — someone outside the system who will always go after the truth. That was hugely appealing. Were you questioning Northern Ireland society and history from a young age?

McKinty: No, I wasn’t like you. I completely bought into the propaganda and the lies. We lived on a hardcore working class sectarian estate effectively run by the UVF (a Protestant paramilitary group). When the hardmen told us kids to do something we did it. Ian Paisley would drive through the estate electioneering and the whole street would come out to cheer. Interestingly neither my mother nor father liked Paisley. My dad wasn’t interested in politics at all and my mum didn’t like Paisley because she considered him uncouth and vulgar. A guy a few doors down from us was arrested for murdering three random Catholic men (so in effect he was a serial killer) and all this seemed completely normal to me. The domestic violence, the drunkenness, the chimney fires every night — all seemed just the way things were done. I don’t think my eyes were opened until I started reading a lot of science fiction and fantasy when I began to see that there were other possibilities of how to live and everything around me was just contingent. When I was about 11 or 12 I read Ursula Le Guin’s "Left Hand of Darkness" and I remember when I was done with that it occurred to me that everything the hardmen said was uneducated, quasi-fascist nonsense.

Did the Troubles impact you as a person and/or as a writer? Do you think the Troubles are still impacting us today even though it’s been two decades since the Good Friday Agreement?

Cavanagh: The Troubles impacted everyone in Northern Ireland, directly or indirectly. Thank god, none of my immediate family were ever hurt or killed, but friends and members of the wider family were killed and injured. When you’re growing up in the middle of it, you don’t think about it. You don’t question it.

I think it did have a massive impact on my mother. Every weekday, around ten past five in the afternoon, I would see my mother start to watch the clock on the living room wall. My dad was a plumber, and he usually got home around that time. There were no mobile phones, so if my dad knew he would be late by more than 20 minutes he would find a phone and call my mum and tell her. If he didn’t call, and he was late, I would watch my mum’s nerves slowly shred. This was the 1980s, when men at building sites, or anyone traveling in a work van, was a target for republican and loyalist terrorists if they were perceived to be made up of largely one religious group, or they carried out work in government buildings. When I think back to the Troubles, that is my enduring memory.

There was plenty of other shit went on in my life back then on a regular basis — fights, bomb scares, even watching a British soldier as he took aim and sighted me through his rifle when I was walking to school (a semi-regular occurrence). I thought of all that as normal, and I don’t remember most of it, but I do remember the dread and the fear in my living room watching my mum as she stared at that clock while I watched kids TV. If he wasn’t home by half five, when "Blue Peter" finished and the credits rolled over that theme tune, her hands would start to shake. Then the local news would come on and she became visibly more agitated. She never let me turn the TV up too loud, even when the news came on, because she was listening for the sound of his key in the front door. Thankfully, he was never harmed, but he had a number of close calls.

I’m conscious now that I’m still desensitized to violence — I don’t write violent books, but sometimes my editors tell me I do have to tone down some of my scenes. This is when I thought I had already toned down the violence in that scene, but it’s still too visceral. There’s very little on-the-page violence in "Thirteen," it’s more a psychological cat and mouse game between Eddie Flynn, the defense attorney, and Joshua Kane, the serial killer whose mission is to manipulate the jury in Eddie’s current trial.

You’ve written about this time in Northern Ireland with the Duffy books, do you think it still infects or influences your work?

McKinty: Not so much now. When I’m writing a Duffy novel sometimes I’ll have nightmares about being in a bomb scare or something like that, but there’s so much geography and time since The Belfast Good Friday Agreement of 1998 that those dreams are very rare now. Thank God.

Last month the Sunday Times published a list of the 100 greatest crime and thriller novels. There wasn't a single Irish novelist on the list and they declared that "Harry's Game" by Gerald Seymour was "the original and best Troubles novel." What's up with that?

Cavanagh: Let’s leave that one. They’ve obviously never read a real Troubles novel, although no disrespect to Gerald Seymour. I read that book and enjoyed it — but it’s like saying that "Stop Or My Mom Will Shoot" is the best Sylvester Stallone movie.

McKinty: You've had tremendous success with series titles and standalones. Which do you prefer and why?

Cavanagh: I can’t say I’ve a preference one way or the other. I enjoy both for different reasons. With the Eddie Flynn legal thrillers I’ve always approached each book as a high-concept story within the series. As a reader I love series and particularly spending time with characters that I’ve grown to love and watching them over many years. With a standalone, it can be more freeing in that no character has to survive by the end of the book — which makes the stakes a lot higher for the reader and writer. I like doing things I’ve never done before — both in story and in narrative style and structure. I’ve changed the narrative structure of my novels over time, moving from strict first-person with Eddie, to third-person and multiple points of view. When I approach a new novel I always want to do something slightly different and more challenging to what I’ve done before and a writing a standalone gives me greater scope for experimentation. Also, I want to be able to write books that aren’t set in a courtroom, and now I know I can do that.

Do you find standalones more challenging that series? And how do you approach them — you’ve written a number of them and each is different. Has writing "The Chain," and the enormous love you’ve gotten for that book forever altered your style and approach to the thriller?

McKinty: I SO much prefer writing standalones. With a standalone no one knows what is going to happen until the final page. Will the protagonist live or die? Will the good guys win or the bad guys? Will it be a happy ending, sad ending or an unresolved ending? Everything is to play for and everything is in a delicious state of unknowing and flux. In a serial novel you know the rules and its comfortable and you can’t betray the reader by changing the formula too much or killing the central protagonist. I respect the readers of the Duffy books so I wouldn’t do that to them. But it’s much more interesting for me to write a book where right up to the last page I can do ANYTHING.

You're on a desert island — you're only allowed seven books until rescue comes in about a year or so. What books do you take?

Cavanagh: I’m going to choose books that will take me out of that desert island, both emotionally and intellectually.

"The Chain." I’m serious man, I loved it. I learned a lot from it too. When a writer knocks it out of the park you can only admire, and take whatever you can from a monster book like that. "The Lord Of The Rings" — one of my favorite books from childhood. Either "Legend," "Waylander" or "The King Beyond The Gate" by David Gemmell — my favorite fantasy writer (maybe I could get these in an anthology so they all count as one). For me, he revolutionized fantasy. The heroes in his fiction were all characters who, in moral terms, had driven past the exit long ago. The action, the characters, are all first class. If you want to write action scenes, or write kick-ass dialogue, David Gemmell is hard to beat. Fantasy that reads like a thriller.

"Bridget Jones’s Diary" by Helen Fielding, because it probably made me laugh more than any other book I’ve read. People forget what a sensation that book became, and just how incredibly funny and heart-warming that book is. "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban" or "Harry Potter and The Order Of The Phoenix." I can’t pick one, but these are my favorite of J K Rowling’s series. A lot of kids are readers because of Rowling, and I can see why. An incredible writer with a once-in-a-generation imagination. Last book is a tough one. Probably "Adolf Hitler, My Part In His Downfall," which is volume one of Spike Milligan’s war memoir. Funny, heart-breaking and a glimpse into the mind of a genius.

McKinty: I loved high fantasy as a kid. Indeed it was one of the escape routes for me growing up in a perverse and crazy situation. From high fantasy I ended up playing Dungeons and Dragons and the even more nerdy MERP (Google it). Whenever I saw Season 1 of "Stranger Things" I thought, shit, that was exactly my life riding through the countryside on my bike to a friend’s house to play D&D and then back to Carrickfergus again where maybe there was a war going on. Lately I’ve gotten back to high fantasy through audiobooks and I’ve been listening to Joe Abercrombie who is terrific.

My seven books would be: "The Peregrine" by JA Baker, "The Cold 6000" by James Ellroy, "Power of the Dog" by Don Winslow, "Pride & Prejudice" by Jane Austen and I completely agree with the Spike Milligan but for sheer comedy I think it is edged out by the "Ultimate Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy" (5 volume set) by Douglas Adams and "A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again" by David Foster Wallace. I think on the island I would like to have a book I have never read but have heard good things about especially a long book. My older daughter read "Beloved" by Toni Morrison in school and raved about it and I haven’t read it so I’ll take that one.

Shares