How many times have you heard that if Democrats want to win back the White House, they need to put up a centrist, moderate candidate who can appeal to the majority? “Own the center left, own the mainstream,” we hear from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

For Pelosi, it is essential that Democrats focus on a centrist agenda and centrist candidates. Yet as we know, this stance has threatened to divide the Democratic Party. The conflict between establishment liberals or "moderates" and progressives has been at the forefront of Democratic Party politics ever since Sen. Bernie Sanders —no, not technically a Democrat — announced his plans to run for the party nomination in the 2016 election. Those tensions have only gotten worse in the wake of the election of a number of progressive candidates in the 2018 midterms.

Four of these new members have gotten an impressive amount of public attention. Referred to as “the Squad,” Reps. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Rashida Tlaib of Michigan and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts have become the most visible face of the new progressive energy within the Democratic Party. They have consistently clashed with establishment Democrats like Pelosi, who has dismissed them as inexperienced, unprofessional and inconsequential. For establishment figures like Pelosi, the new progressive members of the House are a dangerous, fringe wing of the party who may ruin the party’s chance to win back the White House.

But what if that line of thinking is totally wrong? What if there really isn’t a "center" to win over after all? And, what if the way we define the center is skewed?

A new study conducted by Lee Drutman for the Voter Study Group suggests that there are actually very few voters who are consistently in the middle on issues. Instead, he finds that most so-called centrist voters are actually cross-pressured on issues, meaning that they may align with different parties on different issues. For instance, Drutman found that about a quarter of the electorate is cross-pressured on economics and immigration. He goes on to explain that his analysis “finds a relatively small political center.” Instead, the cross-pressured voter holds off-center political views that align with both parties in different ways.

Drutman concludes that there are “relatively few centrists,” showing instead that the electorate remains highly polarized on issues. The catch is that these voters are polarized in ways that don’t neatly align with one party platform.

So choosing the center as a tactic might not appeal to any of these voters. In fact, Drutman finds that only 13 percent of the electorate is truly in the middle across issues.

The reality that the cross-pressured middle is a larger segment of the electorate than the consistent middle throws a wrench into the strategy of appealing to the center. As Drutman puts it, “the center is a relatively lonely place to be in today’s politics.”

But you wouldn’t know that if you listened to establishment Democrats like Pelosi. In response, Ernest A. Canning writes for Common Dreams that is time to stop referring to corporate-money-compromised Democrats as either "centrists" or "moderates." For Canning, the issue is far less about the “center” and far more about corruption — the relationship a particular Democratic candidate has to corporate interests.

In fact, considerable evidence points toward the conclusion that the divide in the Democratic party is defined by the degree to which a Democrat is beholden to corporate power. Norman Solomon illustrated this break in stark terms in a recent piece comparing Pelosi’s stance on meeting with billionaire donors and her interest in meeting with progressive groups. Guess what? The first group gets on her schedule easily. The second, which represents millions of active supporters, gets an email that reads, “Unfortunately, Speaker Pelosi is unable to meet at this time. We will be sure to let you know if anything changes in her schedule.”

Doesn’t this mean that it is high time we swap the term centrist Democrat with the more accurate term of corporatist Democrat?

Yet, there's more. The common belief is that centrist Democrats represents the mainstream majority of voter interests. But what if they actually don’t?

Canning points out that if the term “mainstream” is meant to describe what the majority of Americans want, then it turns out they want many of the core policy positions of progressives. He references a 2018 poll that found that 70 percent of all Americans, (52 percent of Republicans and 84 percent of Democrats) supported Medicare for All. Another 2018 poll that showed that 81 percent of Americans supported a Green New Deal. He further notes that 82 percent of Americans want the federal government to negotiate lower prescription drug prices.

Left leaders like filmmaker Michael Moore have been making this point for years. In a recent MSNBC interview, Moore explained that too much chatter is spent over the mythical white working-class male voter who will supposedly abandon the Democratic party if it shifts too far left on issues. What’s especially weird about this obsession, Moore explains, is the fact that the working class is not made up of older white men anyway. “The majority of the working class in this country are women,” Moore said. And they tend to be young: “When you say working class, you’re talking about young people, 18 to 35.”

“The majority of Americans take the liberal/progressive position,” Moore went on, and they “will come out to vote for the candidate that’s going to side with them.”

Taken together, all this would mean: 1) there are virtually no voters in the so-called center who hold political views that are in the middle of right and left-wing policies, and 2) the majority of voters align with progressive polices.

But that's not all that's wrong with the myth of the center. The largest voting demographic in the 2020 election is set to be younger voters: According to the Pew Research Center, millennials and Gen Z adults will comprise 37 percent of the electorate. There is good reason to think that these young voters will make a difference. In the 2018 election, Generation Z, millennials and Generation X set records for turnout and outvoted older generations.

The political profile of these younger voters is clearly more aligned with left-progressive politics than that of older generations. Yet for some reason these young voters are rarely, if ever, considered the mainstream — even if the math suggests they are, in fact, the mainstream majority.

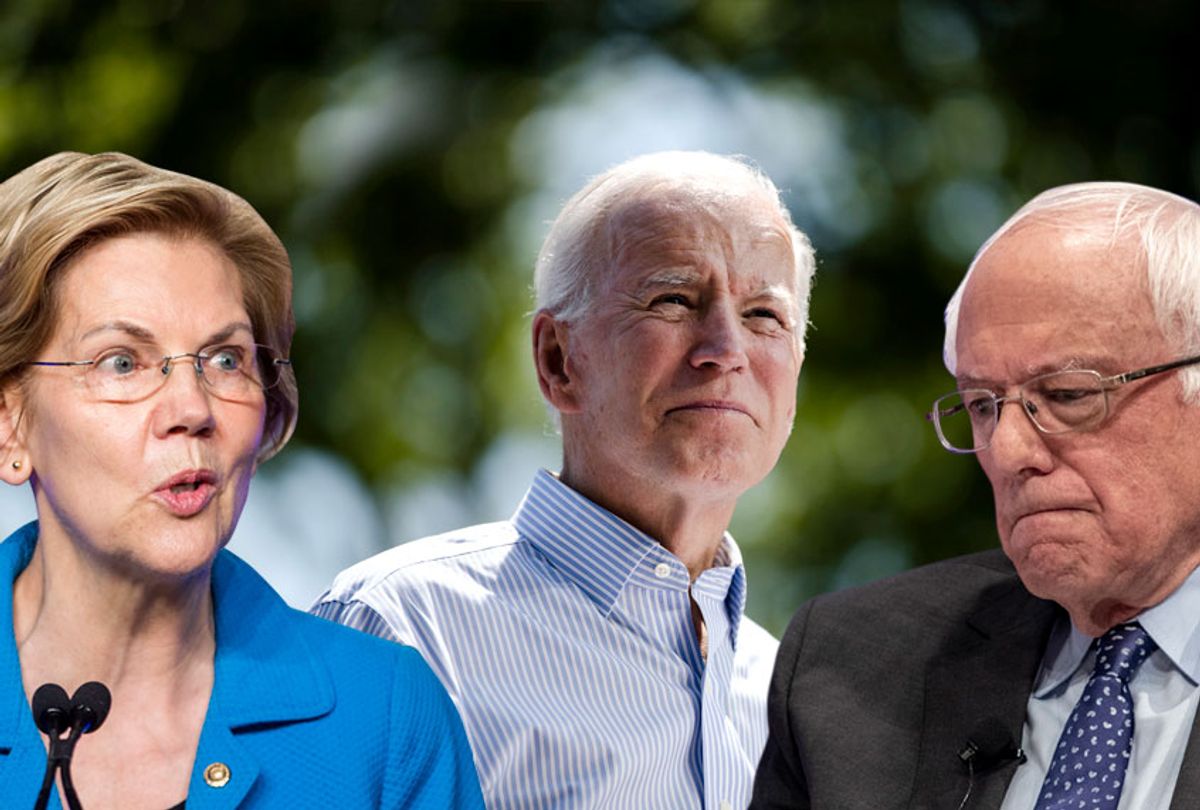

If we were to take these voters seriously and acknowledge their importance, that might also lead to some important questions over the idea of the so-called electable candidate along the lines of Joe Biden.

Much is made of the idea that what Democrats need is an “electable,” “centrist,” “moderate” candidate. As I’ve explained, these words are code for establishment, corporatist and anti-progressive. But for the sake of the thought experiment over "electability," let’s imagine that the only way Democrats win the presidency is by putting up a candidate who is moderate on issues.

A recent set of polls cited by Erin Doherty for FiveThirtyEight calls into question the very idea of electability as an effective strategy. This is because young voters prioritize a candidate’s policies over electability. Instead, “older Democrats were more likely to want an electable candidate even if they disagreed on the issues,” but such a candidate is likely to lead to a depressed turnout among younger voters, a potential catastrophe for any Democratic nominee. Doherty explains that in key battleground races in 2018 it was young voters who often made a decisive difference.

So, if the largest voting bloc values meaningful policies over "electability," then doesn’t that actually redefine the very idea of who is electable? Based on the numbers, the most “electable” Democratic candidate will be one whose policies appeal to young voters.

If Democrats' rhetoric over the political center doesn’t match the math, then maybe it is time to call out that rhetoric for what it is: a myth. The longer we let this myth control the narrative of the 2020 election, the longer we will be trapped in a fantasy that isn’t likely to have a happy ending.

Shares