It’s become media orthodoxy to suggest that the era of U.S. hegemony is slowly slipping away and migrating to Asia — with China as its locus — as we proceed into the heart of the 21st century. There is, however, a competing narrative, one recently expressed by Michael Auslin on ForeignPolicy.com, who makes the case that the “Asian Century” “is ending far faster than anyone could have predicted. From a dramatically slowing Chinese economy to showdowns over democracy in Hong Kong and a new cold war between Japan and South Korea, the dynamism that was supposed to propel the region into a glorious future seems to be falling apart.”

Auslin makes a very compelling case: As he notes, Asia is increasingly falling prey to the kinds of intra-regional geopolitical disputes that have long characterized other parts of the world (Japan vs. China islands dispute, South Korea vs. Japan trade dispute, Beijing’s ongoing efforts to subvert democratic reforms in both Hong Kong and Taiwan, to cite a few examples). Disputes, even rivalry, between nations are expensive. The American growth model came at quite a discount: partner countries didn’t (and still don’t) have to burn their GDPs on economic and military defenses to assure their positions — that alone can siphon off the share of GDP any country would wish it could call “growth.”

Additionally, the region, especially China, looks to be on the verge of consuming its entire available capital and labor resources. Mercantilism is becoming a non-starter, as protectionist backlash mounts, debt-fueled GDP growth is fading and productivity gains are dissipating. That’s a serious problem that is largely underestimated in the West.

To be sure, there have been predictions of gloom before. In 1994, Paul Krugman argued that the bulk of the so-called East Asian “miracle” could be largely explained not by the far-sighted long-term national planning on the part of its mandarin class, but rather via traditional “inputs” common to all emerging economy success stories, notably high savings rates, good education, and the migration of underemployed peasants from the agricultural hinterland into the modern urban centers. Krugman argued that these factors largely explained most, and in some cases all, of the growth in the Asian economic “miracle” (i.e., its growth “output”). His analysis seemed remarkably prescient once the region went down in flames during the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis.

Although the region did recover from that crisis, Krugman’s larger point still stands: if one looks at Asia over the past two decades, trend growth rates in most of the region have slowed down, especially trend productivity rates. The same thing happened earlier in Japan, where potential output (the output a country can produce on average over the course of a business cycle) began declining more than three decades ago, just when some Western experts became convinced that the country was about to surpass the U.S. as the number one economy in the world. (It should be noted, however, that the myth of Japan’s “lost decade” is also massively overhyped and that the country today surpasses the U.S. on many economic and social metrics.)

Japan’s relative decline may have been exacerbated by the fallout from its own financial bubble collapse in the 1990s, but on the whole, it is not an unusual story. Rather, it reflects a typical evolution of economies moving from emerging markets to a higher level of advancement. Unfortunately, many economists and strategists (who today predict that Asia will eventually rule the world) forget this trajectory when they mistakenly extrapolate future trends based on recent past performance.

What about China, which is the real elephant in the room and the main reason why we ought to be somewhat skeptical about the case for the Asian century? There are a variety of assumptions made about the Chinese economy that are questionable. Let’s consider a few.

The consensus has long assumed that China’s labor force is still growing and is likely to do so, well into the future. In reality, that’s not the case. The working age population peaked in 2016, according to the World Bank, and is likely to decline by 10 percent by 2040, in large part a legacy of the country’s one-child policy. That means labor force growth may be turning negative (although the impact might be limited by labor automation, which is extremely highly skilled and high risk). Japan is a world leader here, but its historical rivalry with China does create issues in terms of collaboratively creating a globally dominant Asian economic bloc.

Related to that is China’s “total factor productivity” (TFP), which measures how efficiently and intensely inputs are used in the production process. That too is declining sharply. TFP rose steadily throughout from 1998 onward, and reached an extraordinary level of 8.0 percent in 2003 (almost matching the level of 8.2 percent earlier reached in 1995). It fell again to 2.9 percent by 2004, before rising again to 7.6 percent by 2007. During that period, the migration of surplus labor from low productivity agriculture to the highly productive modern sector was around 20 million people per year. Most of that total factor productivity surge was almost wholly due to this internal migration of surplus labor from the countryside to the urban areas. Since then, the flow of internal migration has probably fallen in half or more, and with that TFP has collapsed, even as the modern sector workforce has doubled.

Lastly, with a ratio of fixed investment to GDP of over 40 percent for several years now relative to a falling trend rate of GDP growth (determined by falling labor force growth and declining productivity), China’s economy has witnessed hugely diminished returns to fixed investment. Capital deepening can no longer be contributing to growth the way it did in the past. Building “ghost cities”, constructing roads to nowhere, and duplicative investments in basic industries (often adding to existing surplus capacity) do not constitute a form of capital deepening that adds to economic growth. The universal goal has to be to have a mixed economy, rather than a redundant one. Michael Auslin’s thesis is validated using the available macroeconomic data available to us.

China’s champions have long maintained that, after the country completes its subways and highways and railways for the 21st century, it will then pass the baton to its consumers, who will be able to enjoy the achieved modernity in full, thereby creating a whole new growth dynamic. But history tells us something else: that when investment booms go bust, they take down the consumers who work in the investment industries first. Recall that in the post-war Keynesian macro model, fixed investment was the driver of the business cycle, and fixed investment always had a multiplier effect — in layman’s terms, the input of capital investment causes a larger change in an output, such as gross domestic product. It is only after this multiplier has run its course that consumer spending can take over within the context of economic growth.

We may be at this stage now in China, but deflating a huge capital expenditure bubble, while shifting the baton seamlessly to the consumer, is unlikely to occur without significant economic disruption. This is because the smaller the share of the consumer in any economy, the harder it becomes to seamlessly spend more to offset a contraction in investment expenditures. Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf himself noted that in 2018, Chinese consumption “was still as low as 40 per cent [of GDP],” implying that this passing of the baton from fixed investment to consumption in the current Chinese context would be far from seamless. That is a titanic gap to fill in five decades, much less a two-year trade war.

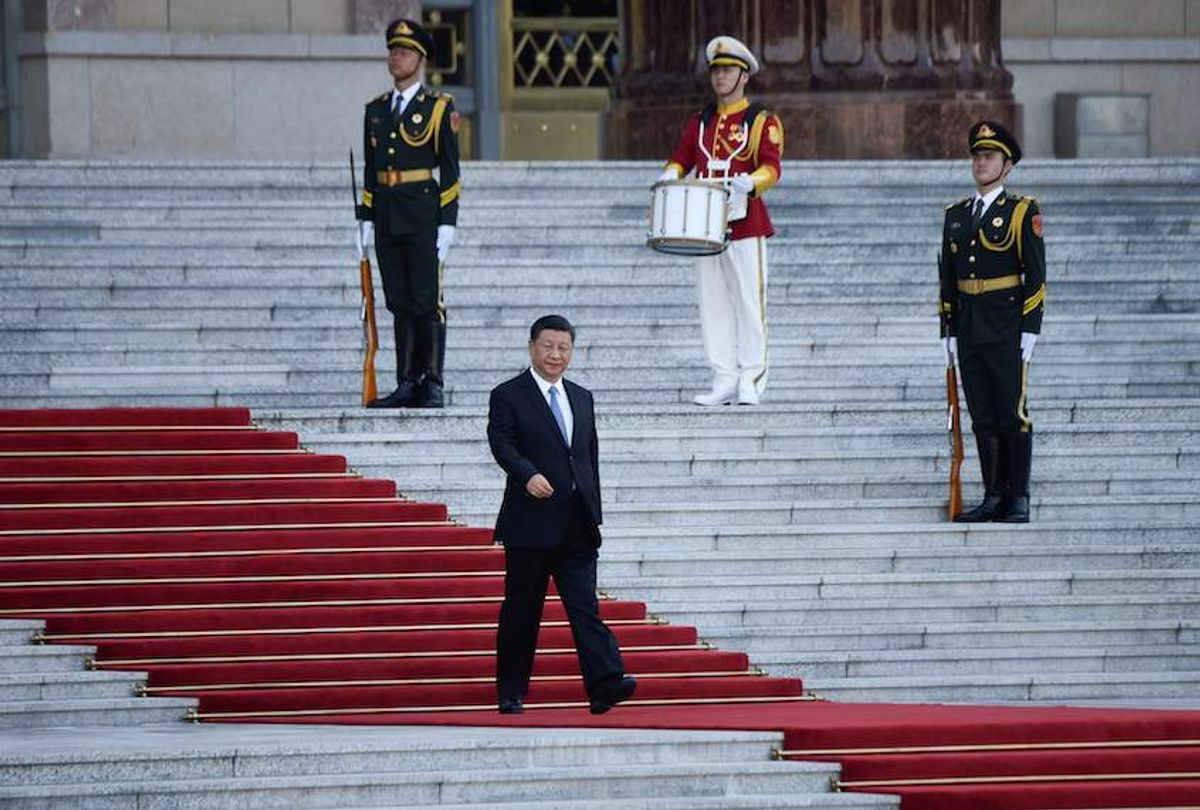

It is a great virtue in many ways that China has gone far down the road as a hybrid economy; that has made it far more efficient and far more responsive than the pure command economy of Soviet communism. But when China’s policymakers deploy fiscal and monetary stimulus aggressively to ratchet fixed investment higher and keep the boom going, their scattershot credit expansion finances not only fixed investment — they have also financed speculation in assets, notably the stock market and real estate. In these credit expansion–fueled booms, private parties — many of them consumers — borrow and speculate in overvalued assets. The scattershot credit expansion not only leads to fixed investment problems; it also leads to households getting deeply into debt with vulnerable inflated assets as their collateral. If that sounds like a familiar plotline, recall how that worked out in the U.S. after the 2008 crash. At least the U.S. has developed systems to mitigate the worst of the resultant shocks. Not so in China, especially as major economic disruption literally poses existential risks for the ruling party, which is already moving in a more authoritarian direction under President Xi Jinping.

Beijing is not oblivious to these risks, which explains their “stop-start” monetary and fiscal policies. The country’s policymakers are seeking to gradually deflate the capital expenditure, real estate and stock market bubbles, without risking a full-blown debt deflation crisis. The problem is that each time the authorities move to avert a deeper financial crisis, the resultant speculation inevitably flows back into those very activities that Beijing is seeking to discourage. Speculation abhors a vacuum.

As Michael Auslin observes, “U.S. policymakers bet that China’s economic modernization and peaceful rise would lead to an era of global prosperity and cooperation, linking advanced economies in Asia with consumers in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere.” But that calculation looks more like a Pollyannaish fantasy today. That’s not to say that this gives new life to American hegemony. Rather, the world is increasingly likely to settle into a 19th-century style balance of power type of regional competitions, of which Asia is but an element, rather than the dominant player.

Shares