Wealthy men soliciting underage girls for sex. Girls lured to expensive homes by promises of good-paying jobs. Captains of commerce and heads of state reveling in debauchery. Officials looking the other way.

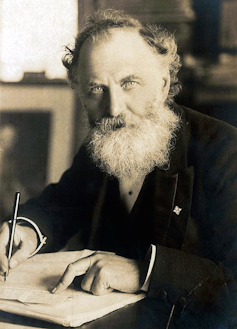

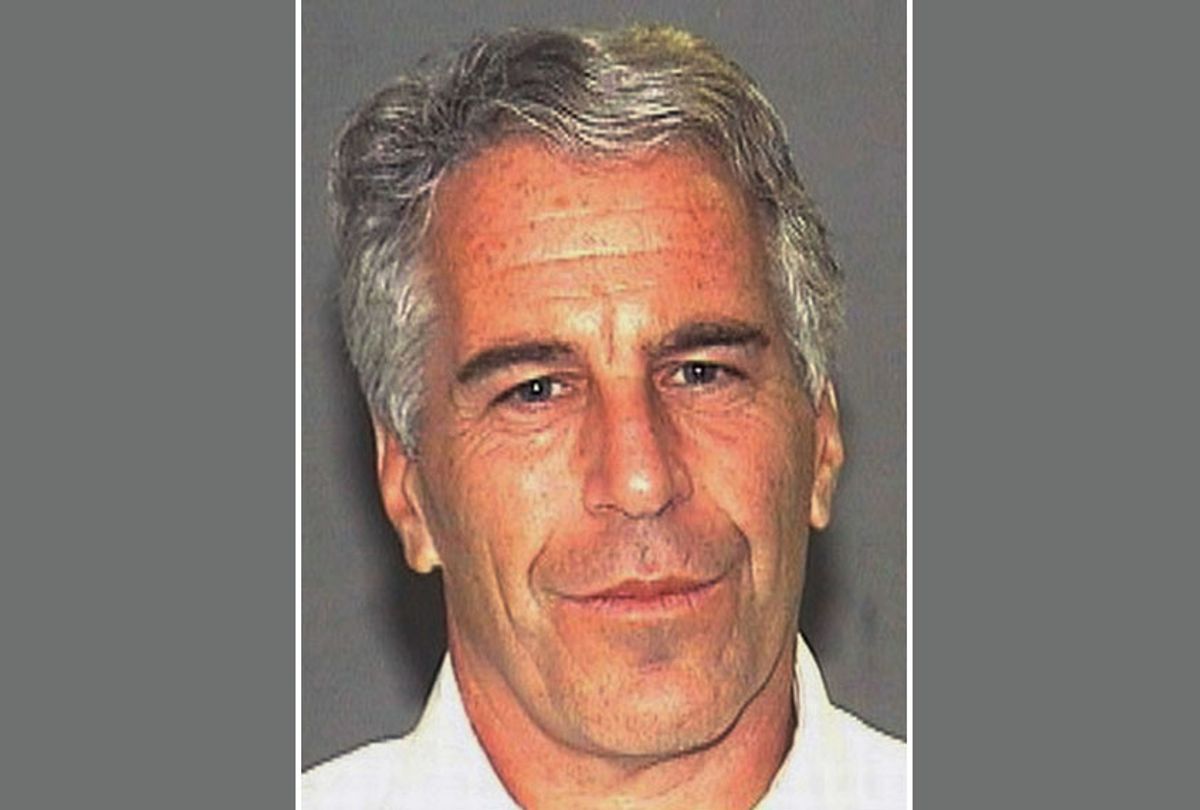

A newspaper exposé written by British journalist W.T. Stead, “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon” sounds just like the sordid sex ring of Jeffrey Epstein, who died of an apparent suicide in prison on Aug. 10.

The difference is that Stead’s account appeared over a century ago, in London’s Pall Mall Gazette in the summer of 1885.

In the four-part series, investigative journalist W.T. Stead graphically detailed the ways that wealthy Victorian men procured young girls for sex. Ironically, Stead was the only one who ended up in jail.

Lured by the promise of a better life

On July 6, 1885, the first article in Stead’s exposé was published. Stead revealed how thousands of girls, most of whom were between 13 and 15 years old, were bought for sex by prominent London men, including a “well-known member of Parliament,” a cabinet minister, a doctor and a clergyman who obtained a 12-year old virgin for £20.

As soon as it hit London’s newsstands, the story went viral. Stead already had a reputation as a fearless editor who advocated “Government by Journalism” and didn’t shy from sensationalism. The Gazette’s reporting was front-page news in the U.S., with The New York Times covering the scandal and the reaction by English authorities.

Wikimedia Commons

Instead of working to swiftly shut down the illicit sex trade and identify those involved, London’s city solicitor ordered police to seize copies of the Gazette and to arrest vendors for selling copies of the paper. Despite — or because — the attempted censorship, copies sold well above their cover price. Thousands waited outside newspaper offices for their chance to buy each new installment.

Those who could get their hands on a copy learned about how women recruited young girls, and how the authorities who knew about it failed to intervene.

Stead interviewed women who explained how they enticed girls to enter the homes of wealthy men with promises of meals, money and jobs. Looking out for “pretty girls who are poor,” brothel keepers and professional procurers recruited orphans, shop girls, servants and nursemaids to “visit” gentlemen.

“The police knew all about them long ago,” Stead added, noting that officers were discouraged from pursuing leads, while prosecutors intimidated potential witnesses.

Stead interviewed some of the men who paid for the girls. They assured him that the maidens willingly — sometimes eagerly — consented. As the member of Parliament told Stead, “I doubt the unwillingness of these virgins . . . it is nonsense to say it is rape.”

The victimized girls told a different story: They were lured with the promise of a better life. They had no idea that the employment agencies they used were actually fronts for prostitution.

Once the girls consented to go into the gentleman’s house, there was no going back. According to Stead, those who resisted were told that they could choose either to be raped and paid, or raped “and then turned into the streets without a penny.”

Powerful predators remain in the shadows

The “maiden tribute” in the series’ title was a reference to the Greek myth in which virgins were sacrificed to the minotaur of Crete, the half-man, half-bull so brutal that a labyrinth was built to contain him. But Stead points out that, unlike the mythic narrative, which required the sacrifice of seven virgins every nine years, modern London was witnessing an exponential number of girls being sacrificed each day.

The abuse wouldn’t stop, Stead insisted, until people started believing the girls.

“When a woman is outraged,” he wrote, “her sworn testimony weighs nothing against the lightest word of the man who perpetrated the crime.”

The Victorian men in Stead’s account were never publicly named. Nor did they ever face criminal prosecution. As a journalist, Stead refused to reveal his sources. And once public attention waned, officials declined to pursue Stead’s leads.

In an ironic twist, Stead himself served three months in prison for abduction. In order to prove how easy it was, he had a procurer deliver a 13-year-old girl named Eliza Armstrong to him. Even though it was done for the sake of his reporting, the authorities pounced.

Stead’s reporting did have one desired effect: It mobilized support for a parliamentary bill that raised the age of consent for girls from 13 to 16. But none of the women who recruited the girls and none of the men who sexually molested them were held accountable.

Different century, same story?

In some ways, the parallels between the men of Victorian London and Epstein are striking.

Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s one-time girlfriend, allegedly acted as Epstein’s procurer. According to The New York Times, one of Epstein’s victims, Virginia Giuffre, fingered Maxwell as the one who approached her and invited her to Epstein’s home, promising that she could learn how to give massages and “earn a lot of money.” Maxwell has also settled several civil suits with Epstein accusers who named her as his accomplice.

Too often, it seems the law serves the interests of powerful men. We saw this in Epstein’s 2007 non-prosecution agreement proffered by Alexander Acosta, who was, at the time, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Florida.

As the Sentencing Project noted in a 2018 report submitted to the United Nations, “The United States in effect operates two distinct criminal justice systems: one for wealthy people and another for poor people and people of color.” Epstein emerged relatively unscathed during his first brush with the law. Rarely do the authorities haul the same powerful men before the courts a second time, as they did with Epstein.

We can thank the dogged reporting of journalists, who, over the past few years, have been exposing patterns of male sexual abuse, making sure to keep the story in the public eye until justice is served. Ronan Farrow’s Pulitzer Prize-winning New Yorker articles exposing Harvey Weinstein’s decades of predation and his articles detailing Les Moonves’ sexual harrassment played a big role in holding both powerful men to account.

Julie Brown and Emily Michot of the Miami Herald revealed the secret Acosta deal and uncovered more than 80 of Epstein’s alleged victims. Due in part to their reporting, Epstein was indicted in July.

With the continued persistence of journalists, victims and the public, perhaps the labyrinths that shield the other minotaurs in our midst will be permanently razed.

LeeAnne M. Richardson, Associate Professor of English, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shares