I sat in a courtroom back when I was in my early twenties. I was anxious and my palms were sweaty and sticky as I waited for the outcome of my future. I wasn’t on trial, but my best friend Tavon was. We were closer than brothers, and did everything together from playing basketball and chasing girls, to hustling on the streets and sharing ideas about the businesses we dreamed of starting one day.

Tavon ended up being arrested for drug conspiracy, which was strange because he wasn’t caught with anything, yet he was pegged as the head of an east Baltimore drug cartel that didn’t exist. We all dabbled in small drug sales, but we weren’t kingpins, and Tavon’s fate should not have been in the hands of a federal judge.

His lawyer told him that the government was offering 27 years, and that if he didn’t take it, he could go to trial and receive 90 years in prison. The federal system he would have been facing had a conviction rate of over 90 percent, so what option did he really have? As of 2019, Tavon has served 14 years in his 27-year sentence.

Innocent people receiving jail time is not strange. Over 90 percent of state and federal criminal convictions are the result of guilty pleas. And it doesn’t really matter if you are guilty or not. If you are charged, prosecutors are given the task of convicting you, as their reputations and jobs are based on stats. This is exactly what happened to Brian Banks.

Banks was an all-American high school football star with a full ride to USC, until he was falsely accused of and convicted of rape by a classmate in the prime of his athletic career. Despite the gross lack of evidence and conflicting stories from his accuser, Banks, who maintained his innocence the entire time, was forced to take an unfair plea and sentenced to a decade of prison and parole. After serving five years, he had to register as a sex offender.

But Banks didn’t give up. Determined to clear his name, Banks earned the support of Justin Brooks at the California Innocence Project, who fought to fully exonerate Banks and ultimately helped him fulfill his dreams of becoming a professional football player.

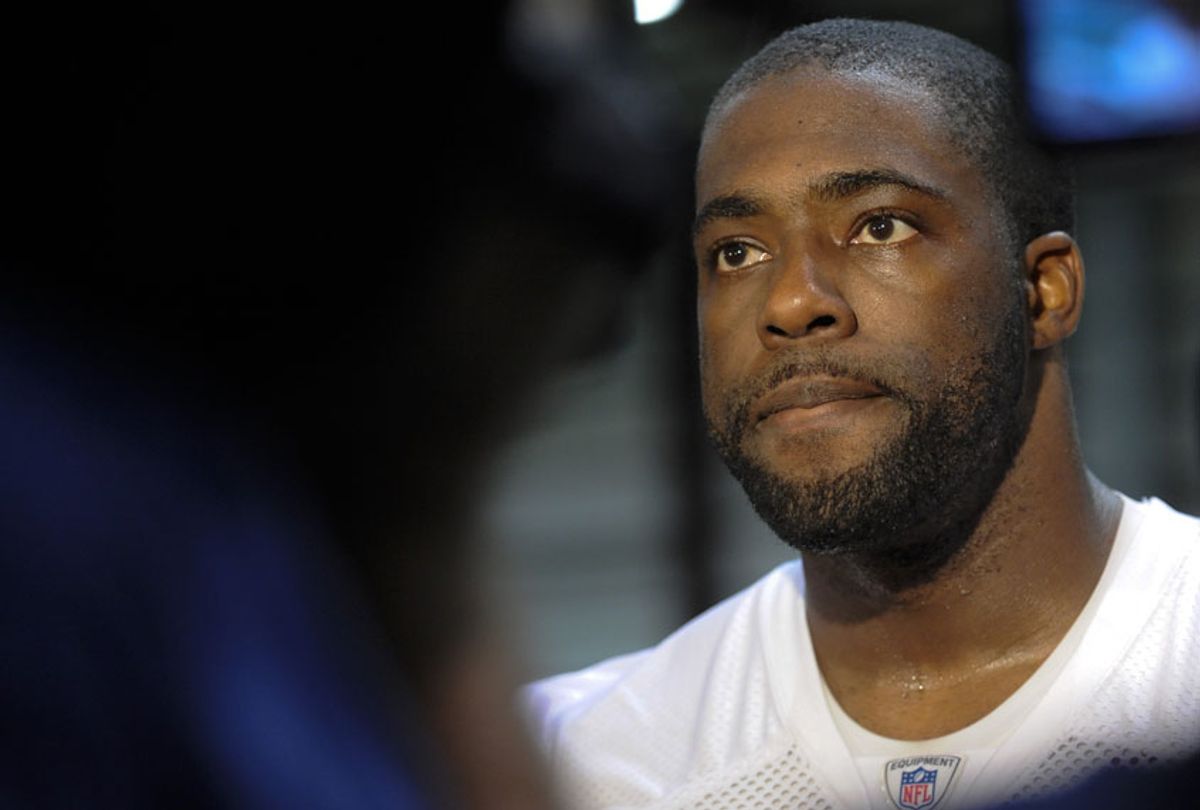

"Brian Banks," a new film in theaters now starring Aldis Hodge (who plays Banks) and Greg Kinnear (who plays Brooks), follows the story of Banks’ wrongful conviction as a teenager.

Banks and Brooks sat down with me on "Salon Talks" for a conversation about the film and the problems in America's criminal justice system that allow stories like Banks' to continue to happen.

Watch our "Salon Talks" episode here, or read the Q&A transcript of our conversation below, edited lightly for clarity and length.

Was it difficult reliving some of those stories or just watching it?

Brian Banks: Absolutely. People have an opportunity to see a film that discusses a 10-year ordeal in the span of 90 minutes. But this was a life journey for me and it was definitely tough reliving some of these moments.

Your story is extremely rare. And in your case, which surrounds a sexual assault allegation, everything is not black and white. In the age of Me Too, did you face trouble with nature of your story, as you were putting the film together?

Justin Brooks: Yeah, that issue has come up and what I always talk about is the overwhelming majority of claims of rape are accurate and in fact there's lots of women who are raped whether or not reported, but that doesn't mean we can ignore the percentage of innocent people are in there.

There's a real problem in this country that everything now is black and white. It's all one thing or another and that's not the reality. I always talk about that there's two naïve positions about prison — one is that everyone in prison is innocent, the other is that everyone in prison is guilty. The truth is most people in prison are guilty. You've got to figure out what does that "most" mean and how big is that crack. And Brian is a human being who fell through that crack and we got to care about that.

The film focuses on the stigma that comes with sexual assault. Brian, you know you're an innocent person and that you didn't do anything wrong, but at the same time how do you live with the idea that you were accused of this?

Banks: I don't wish my experiences on anybody. You know, it's one thing to be incarcerated and accused and convicted of something that you didn't do. It's another to walk the streets labeled and branded a monster, an offender, someone has taken advantage of a woman. It's really indescribable the feeling of being on a sex offense list.

When someone wants to move into your neighborhood and they want to know if that neighborhood is safe, they get on the website to check it out. Your name shows, your face shows, your crime, your address. So it's tough and humiliating. You know, you deal with all the people who judge you, you deal with all the people who don't really know the truth. And so therefore they just go based off of, you know, what they've seen in your court proceedings and so forth.

At times did you ever feel like you didn't even really want to go outside?

Banks: Absolutely. You know, it's crazy because they labeled and deemed me a monster, but in fact I was the one who would leave out of my house every day looking over my shoulder and being afraid of someone recognizing me or coming after me because of what they read online or what they saw in the article, whatnot.

At the same time, through reading your book and watching the film, it seems like you've always had very high spirits. Is that the case? Like do you meditate or do hot yoga or something?

Banks: I grew up in a household where all we did was laugh and make jokes and so I think that carried with me throughout my life, just kind of being lighthearted and finding ways to be positive and in crazy situations. But this was an ordeal and a traumatic experience that required way more than just laughter and smiling faces. It really required me to discover who I was as a spiritual being all the way down to the spirit, you know, and just try to have more of an understanding of myself, my capabilities, the power that I have within me to control my emotions and not let them control me.

Justin, when did you first meet Brian?

Brooks: Brian is the first client I've ever had who was out of prison. You know, we're so overwhelmed with work at the California Innocence Project. We can't represent guys who want to clear their name or get off parole. We're dealing with lifers and we’re dealing with people on death row. But you know, Brian's case was just so compelling for two reasons.

Number one, he had so much taken away from him. Most of my clients just had regular lives and we're trying to get them back to it. Brian was going to go to the NFL. Brian had this incredible career ahead of him. And the second thing is Brian had this compelling evidence of innocence that was not necessarily going to pass the evidence standards in court, but clearly showed he was innocent. And that's frustrating.

It's frustrating how the way our system is set up that sometimes you got evidence and you're innocent, but because of our rules of evidence, you may not be able to introduce it. So everybody in my office wanted to get on board with Brian's case. And it was also important because Brian represents the 95 to 97 percent of people who plea out in this country and we need to get that issue out there, that now it's become a business decision. Innocent people are pleading cause they just don't want to risk losing their life.

I think it's a missing component of the entire criminal justice reform conversation. I've been through the system, the bulk of my friends have been through the system, and people who look at us from the outside are just like, "Oh yeah these street guys. Are they hustling?” Some people in jail right now didn't do anything wrong, but just like what happens to you in the film, somebody comes to you and says "Look, you can take this three to five, or you're never going to come home again."

Brooks: And it wasn't always like that. The lawyer will even say that to you: "Look, whether you did or not is not relevant." Not relevant?

Banks: That's why I'm here.

This is why America locks up more people than anybody else in the world.

Brooks: And as we continue to increase those incarceration rates. We've lessened the number of resources in the system. And now very few cases can go to trial. We don't have the resources to do it. And so you'll sit there and say, "Look dude, it doesn't matter whether you did or not. The way we're going to look at this case is what is the evidence they have against you and what's the risk you have of going to trial." It just becomes a business decision.

And then you put in Brian's case, you got a 17-year-old kid sitting there having to make a life or death decision, having a few minutes to do it. It's like you go to a doctor and the emergency room and he says, look, we've got to do emergency surgery on you right now. Now you can do the surgery or die. And that was the situation that Brian was in. It was either take the advice I'm giving you right now or die and it doesn't really matter what the truth is in that.

Brian, let’s talk about your state of mind being a person who is innocent. Bring us into your mindset when you were initially accused.

Banks: At the time I was picked up off the streets, I was 16 years old. I was eleventh in the nation as a linebacker for Long Beach Poly High School. It was the summer going into my senior year, the biggest year of sports for me at that time. I had never been arrested, never been locked up, never had a jaywalking ticket, never had any run ins with the police before. And then all of a sudden I was in, I was in handcuffs and being forced out of my house and being placed into a police car and then taken to a medical facility where they performed DNA testing on me, which is very personal, you know, for them to be swabbing you and pulling at you're pubic hairs and doing different things to you.

And I'm 16 years old when all this is taking place. Before there was even a discussion of jail or being locked up, there was this whole invasion of privacy, of my body, you know what I mean? Then just the first two weeks of incarceration, I lost 14 pounds. I wasn't eating food, I wasn't coming out the cell. I wasn't interacting with the people. Everybody kept telling me this would be figured out, so I just sat there and waited.

In your case, the DNA test was not even used.

Banks: It was never used, but yeah, it was some of the hardest moments of my life, those first few weeks of incarceration. Just knowing that I wasn't supposed to be there, knowing that my school year was about to start and the football season was starting up and you know, to hear that my school district had expelled me from the district regardless of the outcome of what happened in the case, you know, it was just a lot to take in at such a young age.

Guilty before you even get a chance to go through trial.

Banks: Yeah.

Justin, how common is Brian's case?

Brooks: We receive over 6,000 letters a year of people who have claims. We look into every single one of them. The problem is almost none of them have proof of innocence, just like Brian wouldn't have had proof of innocence. Brian wrote us twice from prison and we had to say, look, there was no evidence that convicted you and there's no evidence of your innocence either. There's no evidence in this case, and in our country, you have to have extraordinary evidence to come back into court and get your case reopened.

So yeah, if you've got a great DNA case, but most cases, I have nothing to do DNA. You know, you've got drug cases, I used to represent clients in DC, kids. If you're living in that neighborhood and the police raid that neighborhood, all the kids on the street get picked up, they're all going to get charged with drug trafficking. How do they prove they're innocent? How do they say, “I'm not with these kids.” You don't even have to have the drugs in your pocket to get charged with possession of them.

The hardest part of this work is the thousands of people we can't help because that's where the system is set up. And because they get pushed through it at the trial level, through these plea bargains, and by the time I take a look at the case, it's too late. You know, if I could get in a time machine and go back, we could fix it, but otherwise we can't.

What is the fix though? We know some police officers do come in with good intentions, but for others it seems like they target whoever they feel like locking up. We also know some of these prosecutors look at stacks of police reports, see the lies and they still push them through.

Brooks: It's even bigger than that. It's the whole system. We suffer from 30 years of tough on crime politics and it goes back to Willie Horton and Mike Dukakis, which I'm old enough to remember. That's how George Bush the first became president. He came up with this great idea, "Why don't we say Mike Dukakis is responsible for that?" because he was the governor and granted him parole. Ever since then, every politician has learned it pays to be tough on crime. You get money from the corrections industry, you get support from the police department unions, you get support from the correctional officers’ union and you get votes by scaring people. And so we filled our prisons, we've overwhelmed the criminal justice system, and now almost every case gets pled out. Brian's case is exactly the result of three decades of bad criminal law policy.

How do we change the system?

Brooks: We've got to decriminalize things that shouldn't be criminal. We've got to lesson the sentences. We've got to start doing rehabilitation programs in prison so we don't have a 70 percent recidivism rate where everybody's coming back in the system. We got to use common sense and stop just doing knee jerk reactions out of fear or out of the vengeance because none of this does anything for us.

You know, even after Brian was exonerated, we still had to go around and get him off all these sex offender lists, to help him get a job. Brian was carrying around the cover of the Los Angeles Times to show he’d been exonerated to rent an apartment. These are the kind of hurdles we put in front of everybody and then we're surprised when the system doesn't work.

Brian, your mom, played by Sherri Shepherd in the film, was a soldier throughout the entire story.

Banks: Still is. She really went through it, man. I always tell people I know what it feels like to be wrongfully convicted and put in a cell, but I have no clue of what it feels like to be a mom. To watch your kid be snatched from your protection, from your care, for you to do all that you can to save your kid. And it just falls on deaf ears. I do not know what that feels like, but she does.

What would you say to a kid, the 16 or 17 years old, innocent or guilty, sitting in a cell right now, who wants to be able to do something positive with their lives?

Banks: The harsh reality is unfortunately that it may get worse before it gets better. Once the system gets their hands on you. They got you. It's easier for them to put a charge and a crime against you than it is for you to prove and vindicate yourself from the accusation. It boils down to trying your best to find someone who's actually going to fight for you, that will really fight for you. And not just say that they will to collect a paycheck.

If there's a family member of someone who is behind bars right now listening, stay in their lives, be supportive, be very supportive because there is no feeling like being alone in a cell. You're already alone by yourself physically. Emotionally, to be alone is a whole different struggle, so never leave their corner and be with them. And for the person who is behind bars, the only thing that you can control is yourself. In an uncontrolled environment.

Film is having a major moment right now in shining a light on the harsh realities of the criminal justice system, from “Brian Banks,” to Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us,” and following Dream Hampton's “Surviving R. Kelly,” R. Kelly has been arrested. Can you speak to the idea that art has the power to make change?

Banks: I think it's extremely important that we inform people about the realities of our injustice system in as many ways and in any way that we can. It's kind of easy to push people along through a system cause no one's fact checking it and no one's really looking into what's happening, so I think it's important that people become more informed about what's going on. I think people should take part in jury duty, probably stop ducking jury duty. We've got a lot of complaints about all white juries.

Brooks: And art is important because things like Brian's book that he wrote and just put out and this movie, they're going deeper. I've been doing this work for 30 years and it's the same news footage every time, right? They want the picture of the dude walking out of prison. They want to see him eating that first meal, but it never goes that deep into what really happened here. How do we analyze this plane crash that happened in this person's life? And so this movie does that. Brian's book does that.

Shares