When I tell someone that my family doesn’t have any old home videos of me and my brother, I am often met with pity — as though my childhood were a wash by virtue of lack of physical documentation. My parents weren’t heartless: they documented hours of video footage of our family using physical tapes for years after we were born. But on my brother’s seventh birthday, our house was robbed, and the tapes were a casualty. In my parents' telling, the robber probably wasn’t interested in our home videos, but was just in a rush to grab what they could. The video camera and VHS tapes just happened to be in the same bag in the closet.

Now, in the smartphone era, there is no excuse for not video-recording every aspect of a child’s life — much less an adult's. The normalization of cloud storage, and its concomitant freemium model, lets most consumers access photos and videos across all devices; hence, burglary no longer means the loss of childhood media archives, as it did for my family. Coming of age in a perennially online epoch, my reliance on this kind of instantaneous accessibility has only grown with each passing year. I don’t have to travel to my grandparents’ house and locate their photo album to access a ten-year-old memory; now, I can do it on-demand from anywhere in the world from my gadget. That kind of spontaneity is addictive. And for better or for worse, I am not alone in this sentiment.

It goes without saying that a smartphone has become essential to our daily lives beyond photography and video. One seems to not exist without a certain level of digital connection to the world around them. And out of all tech companies, Apple seems to understand this the best. Take it from a former Android devotee.

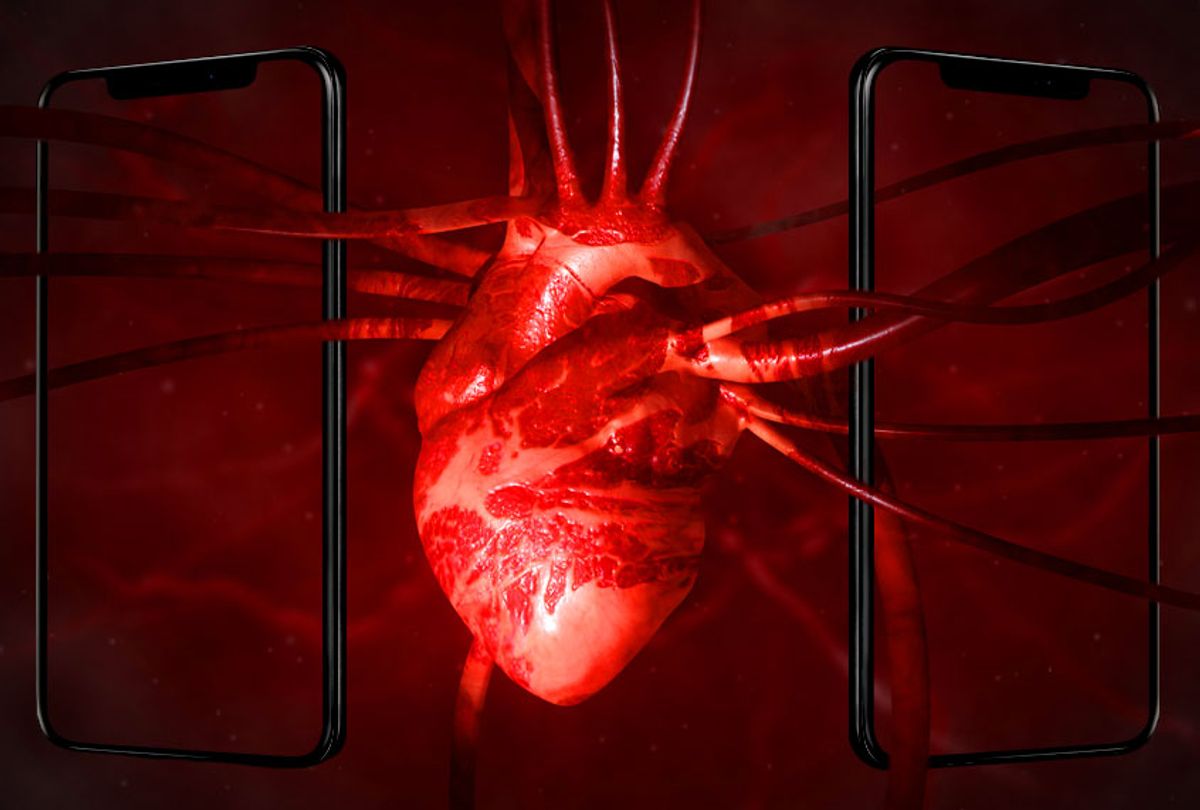

Over a month ago, I switched to the iPhone XR from a Samsung Galaxy S8. In terms of agony, the process leading up to that decision was comparable to the process of buying a car. The days that followed my switch were surprisingly satisfying – I FaceTimed with my mom for the very first time. I was both gratified and beguiled by the simplicity of Apple's interface. Sinisterly, the phone was becoming more than just a smartphone: it became an extension of myself, in a way I had not felt before with my Android. I felt I could connect more deeply with others — specifically other iPhone users — with my new gadget.

These feelings are exactly what Apple wants to evoke in consumers. They want to conjure the same emotions that one feels for a human, but in their inanimate gadgets.

There is a word for this squirrely psychological tactic: Lovemarks.

Lovemarks refers to a marketing concept that public appeal of a product must be created through emotional resonance — ideally, through the channeling of that most primal emotion, love. The idea is that emotion leads to action, whereas marketing campaigns that seek to be informative or reasonable only lead to conclusions. Thus, brands employing this strategy strive to create products or advertisements that make its consumers feel higher levels of love, human connection, and purpose in life. Naturally, a former Saatchi & Saatchi CEO popularized the idea in a 2004 book of the same name.

Apple products and ad campaigns are adept at employing lovemarks — perhaps too much so. Last year’s “Behind the Mac” ad campaign explored the idea that Apple computers allow "creatives" to explore their crafts (“passions,” as Apple puts it) through a series of intimate black and white portraits.

On Apple’s website, the company describes the iPhone XR using the following adjectives: innovative, magical, responsive, delightful, unique, intuitive. The series of descriptors seem more appropriate for describing an admired person, or a treasured memory, than a smartphone.

The lovemarks strategy is embedded into the functionality of the iPhone. FaceTime, the aforementioned video call app, lets users video chat with up to 32 people at once, as if to emulate a face-to-face conversation with many friends or family members. The text effects in iMessage have, I feel, brought me closer to others than a generic text message could — I love to send the heart balloon effect to my mom, to let her know I’m thinking about her in a unique way. The effects make a text conversation less emotionless and (seemingly) closer to real human interaction.

There is a dark irony underlying this sense of intimacy. Since the iPhone was first introduced to the world over a decade ago, many workers within Foxconn — Apple’s primary manufacturer responsible for assembling iPhones, iPads, computers and iPods — have suffered labor abuse, sickness, and – in some cases – death. Foxconn is only one contributor to Apple’s business. Although Apple does not provide information on the number of victims affected by their entire supply chain, it is estimated that it is well into the thousands.

In 2012, a building explosion at a Foxconn factory caused the death of two workers and injured over a dozen. Employees frequently work excessive overtime, live in crowded dorms, and develop serious medical conditions due to being overworked or working in dangerous facility conditions. More recently, some Chinese Foxconn workers were forced to break the law in order to make a living wage: the living wage for an iPhone worker should be about $650 per month, as of 2017. But in order to achieve this financial goal, 80 to 90 hours of overtime are required each month – well over the legal cap for overtime work.

Despite all of this, Apple was awarded the Stop Slavery Award from the Thomson Reuters Foundation in late 2018. It was reportedly in recognition of Apple’s “giant leap in the fight against slavery” through their increased “transparency” about their supply chain. They’ve released a number of documents over the past few years that detail their efforts to combat issues that they’ve been accused for, such as human trafficking and harmful waste disposal practices, but their progress is debatable.

While Apple touts their commitment to informing their 2.4 million workers of their right to unionize, there is a vast gulf between words and action. The workers’ union at Foxconn is run by management themselves — and has been proven to be just as ineffective as if the union did not exist.

Additionally, Apple has publicly announced that they would continue to partner with “independent third-party audits” without providing information on who these auditors are and how effective they will be in combatting the dark side of their supply chain – a key detail that undermines the “transparency” that led to their Stop Slavery Award.

The cost of an iPhone is, in some cases, the cost of a human life. While Apple continues to publicly tout its ability to foster human connection and emotion in this modernizing, digital world, real human beings are suffering at the hands of their supply chain. And how can we possess such emotion while holding something so destructive to a human life?

It’s a difficult truth to reconcile with — and not one that I "love."

Shares