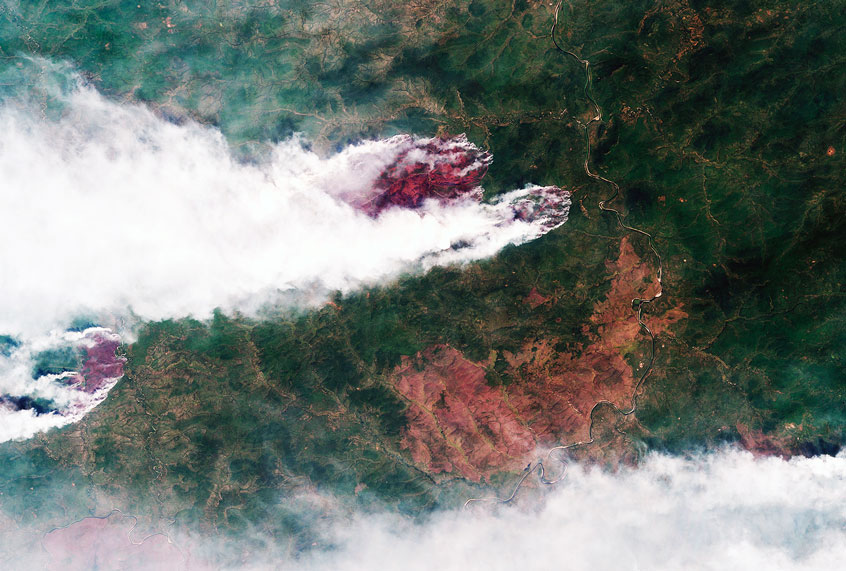

It is not just the Amazon rainforest that is burning. More than 21,000 square miles of forest caught on fire in Siberia this month. That means that Russia is on track for its worst year on record for wildfires.

Since July, wildfires have been spreading in northern Krasnoyarsk Krai, the Sakha Republic, and in Zabaykalsky Krai, where the fires began. At the end of the month, the Siberian forest fire stretched across 6.4 million acres.

According to the Russian News Agency TASS, the Krasnoyarsk Forest Fire Center said that the causes of these forest fires were natural, originating in a combination of high temperatures, strong gusts of wind, and dry thunderstorms with lightning strikes. The average temperature for that region is typically between 58 and 65 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer; lately, temperatures have been recorded in the high 80s.

Russia has the largest forested area in the world, and the northern forests cover about 45 percent of the country. Scientists estimate that Russia’s forests constitute 19 percent of all world forests in terms of area. Likewise, Scientific American reports that boreal forests like those in Siberia sequester 300 to 600 million tons of carbon dioxide every year. That is a huge chunk of the 1.5 billion tons of carbon sequestered overall by Earth’s boreal forests.

A majority of the fires are in inaccessible areas. Russian president Vladimir Putin and officials have reportedly said they will only extinguish them if the cost of destruction is more than the price to put them out, which is not yet the case. This fire-righting strategy is based on a law from 2015.

Yet critics say that is not the right strategy, partly because the smoke from the wildfires has traveled and lingers in the nearby cities of Novosibirsk and Krasnoyars. These cities are hundreds of miles from the epicenter of the wildfires, yet are homes to millions of people, posing serious health threats.

“When the law was drafted in 2015, it never occurred to anyone that the wind would be able to bring smoke from the fires so far,” Andrey Sirin, director of the Institute of Forest Science at the Russian Academy of Sciences, was quoted as saying in the Los Angeles Times. “Often the damage to people’s health is much worse than the damage to the economy.”

However, similar to the fire in the Amazon rainforest, there could be a huge price to pay for letting these fires rage on their own. Like the Amazonian fires, the Siberian fires have the potential to accelerate global warming.

“These fires should have been put out at the very beginning, but were ignored due to weak policies. Now it has grown into a climate catastrophe that can not be stopped by human means,” Greenpeace Russia wildland fire expert and volunteer firefighter Anton Beneslavskiy said in a statement. “Russia should increase efforts in forest protection and provide sufficient funding for firefighting and fire prevention. The problem of wildfires should be addressed at the international level in the global climate agreements to keep global warming below 1.5°C.”

Since the wildfires are up north, their ash and soot, which releases black carbon, pose a massive threat to the Arctic region’s ice sheets. They could accelerate melting, which will increase the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere. With less nearby forest to absorb it, this carbon will contribute to global warming at an unprecedented rate. Likewise, melting of the ice sheets might free previously-trapped permafrost methane, a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide and which is not absorbed in photosynthesis.

“We think we have a handle on the trajectory of warming, but if we have this unexpectedly large release of methane from permafrost, then we’re going to have to change our assumptions about how fast warming is going to occur, and that change would be faster,” Brian Brettschneider, a climatologist and post doctoral fellow at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, told Time magazine.

As the Arctic faces extreme weather, that could increase temperatures across the world.

“Cold air has to come from somewhere, cold air doesn’t just magically appear, and that somewhere has to be accounted for in the entire energy balance of the Earth. Right now the whole Earth has just warmed up,” Brettschneider said.

Some scientists aren’t surprised by the erratic temperature in the Arctic. Philip Higuera, a fire ecologist at the University of Montana, told BBC: “I’m not surprised – these are all the things we have been predicting for decades.

Despite Russia’s lack of effort to put the fires out, some experts say what is really needed is a massive rainfall.

“You need a huge amount of precipitation to fall to put these out – but if you get just a moderate amount of rain, that often comes with lightning, which can just blow things up thanks to the methane in the peat, and just make it worse,” biologist Merritt Turetsky of the University of Guelph, in Ontario, Canada, told the BBC.