Sparked by the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, cities all across the American South are reckoning with their Confederate statues. Some of these are monuments that honor well-known figures like Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson, while some are meant to commemorate the unknown fallen.

In Louisville, Kentucky, where I currently live, the city has spent over two years in tumultuous debate over the fate of the John Breckinridge Castleman statue. Not long after the Charlottesville rally, protestors with “Black Lives Matter” signs surrounded it, chanting “Take it down, take it down.” Castleman’s service in the Confederate army (and his dying wish that his casket be draped with both an American and Confederate flag) had somehow conveniently escaped public knowledge for decades.

Located in a tidy, landscaped roundabout in a white, affluent neighborhood, the statue was, to many, merely “a man on a horse.” But this, in and of itself, raises a question: throughout the history of public statuary in the US, who actually gets to be memorialized in such a fashion? Who gets to be the metaphorical “man on a horse?”

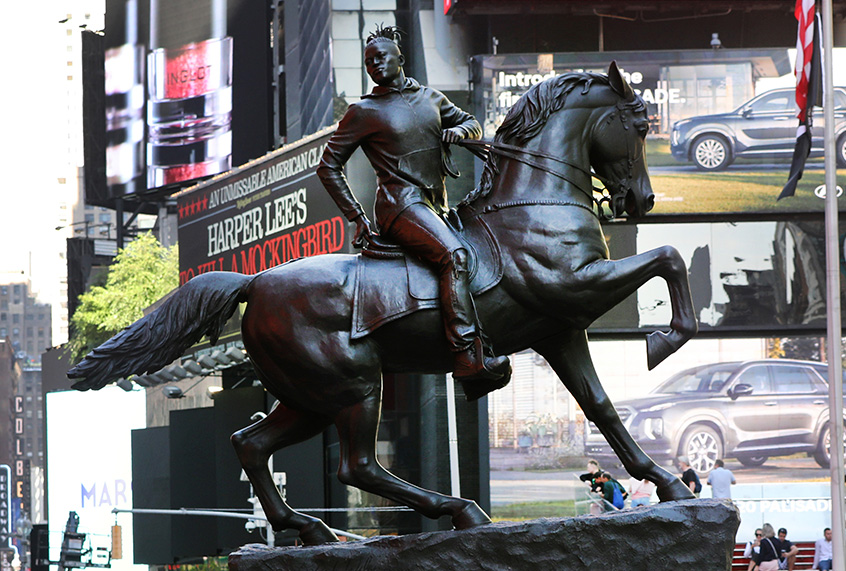

A new public artwork, which was unveiled in Times Square on Friday, dives into this question, too.

“Rumors of War” is an enormous — 27 feet high, 16 feet wide — statue of, yes, a man on a horse. But this one has his hair in dreadlocks and is dressed in ripped jeans and a hoodie. Created by artist Kehinde Wiley, who painted President Barack Obama’s iconic presidential portrait, the monumental work is meant to serve as an invitation to question our collective history and its heroes.

In a statement before the unveiling of the statue, Wiley said that he first had the idea for “Rumors of War” when visiting Richmond, Va. While there, he saw a statue of General J.E.B. Stuart, and its ties to the “Lost Cause,” the ideology surrounding the belief that the cause of the Confederacy during the Civil War was a just, heroic one.

“I’m a black man walking those streets,” Wiley said. “I’m looking up at those things that give me a sense of dread and fear.”

In her article for JSTOR Daily, arts writer Allison C. Meier dives into the history of equestrian statues.

“From emperors and kings to generals and political leaders, a cavalcade of bronze riders stride through our public space,” she wrote. “They are mostly men, except for a few rare depictions of queens, empresses, and Joan of Arc. It’s a commanding visual of action and power. And the style achieved its popularity thanks to one statue in Rome.”

That statue is of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, dating to around 175 CE. In the centuries that have followed, the way numerous leaders have been portrayed mimic that statue’s pose and size.

“Notably, the larger-than-life Marcus Aurelius, who oversaw warfare in his reign, has his arm in the adlocutio salute that an emperor would give his troops, but he holds no weapons and has no military trappings,” Meier wrote. “Shaping popular perception of benevolence and peace through statuary became just as essential as reinforcing power.”

Wiley has a history of creating work that places images of young African Americans in artistic traditions that have been typically reserved for wealthy white people — specifically portraiture in the style of what would have been commissioned by Renaissance aristocracy. His paintings are often a mash-up of the stylings of the Old Masters and references to modern street style; for example, Wiley’s piece, “Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps,” shows a young black man in modern army fatigues, a white bandana and hiking boots riding a white stallion.

“Rumors of War” continues this artistic tradition.

The vast majority of monuments to the Confederacy were erected during the Jim Crow era as a larger-than-life glorification of white supremacy and a government that sought to perpetuate and expand slavery; they’re a reminder of past power — one that has a frightening and enduring hold on America today.

Wiley’s work seeks to empower those who have been systematically oppressed and ignored. Eventually, “Rumors of War” will be moved to Richmond. It will be be erected near the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, blocks away from the Confederate monument that inspired its creation.

“Today,” Wiley said in his statement before the statue unveiling,“we say yes to something that looks like us. We say yes to inclusivity. We say yes to broader notions of what it means to be an American.”