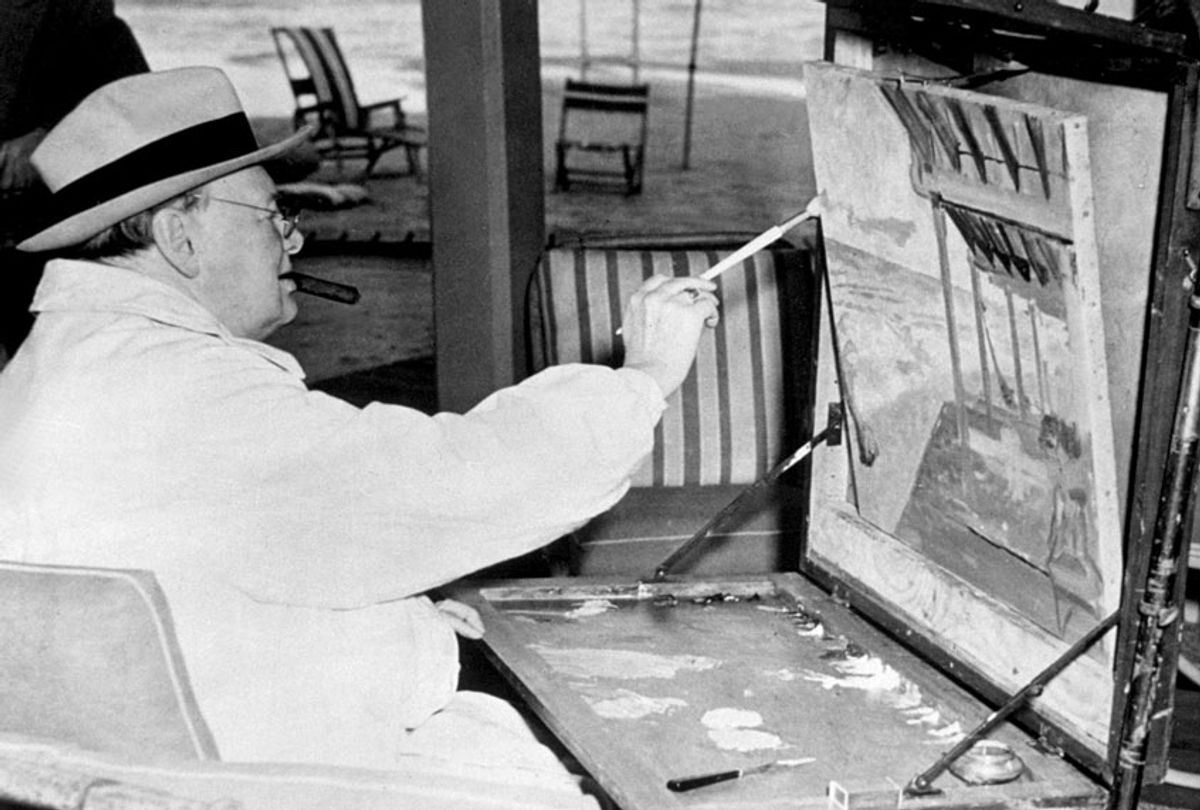

Winston Churchill was a mediocre painter and a worse bricklayer, but to these two hobbies, the world owes a great debt.

"It is a pushing age," Churchill wrote his mother as a young man, "and we must shove with the rest." His ambition was legendary. Multiple times, he shoved his way to the top of British politics, when Britain was the world's dominant power. Once he was there, he did not let up. During war-time, it was not uncommon for him to work 110-hour weeks. Between 1940 and 1943, he traveled something like 110,000 miles by air and sea and car. A bodyguard once said that Churchill kept "less schedule than a forest fire and had less peace than a hurricane."

It's this exhausting workload that is worth examination in a time of "millennial burnout," and digital distraction. More and more people fear that taking their foot off the gas for even a second will only cause them to fall further and further behind in a rigged economy that cares little for individual happiness. Certainly, it's something I've wrestled with as I look back on my very busy twenties (six books and three careers) and look forward towards my thirties with children.

So how did Churchill manage? How did he not burn out and die early? How did a man with so many responsibilities that on a piece of notepaper he once sketched himself a pig, loaded down with a twenty thousand-pound weight, not only survive the workload of two wars, five kids, 10 million written words and live into his 80s, but do so without ever losing his trademark joie de vivre?

The answer is simple: The restorative power of a good hobby.

As it happens, Churchill believed in the power of hobbies almost as much as he believed in British exceptionalism. He was an avid practitioner too. Writing in one of his lesser known books, "Painting as a Pastime," Churchill explained that, "The cultivation of a hobby and new forms of interest is...a policy of first importance to a public man. To be really happy and really safe, one ought to have at least two or three hobbies, and they must all be real."

A few centuries before Churchill, Aristotle said that this was in fact the main question of life: What do we fill our non-working hours with? What do we do for leisure?

Churchill knew the power of cultivating a good hobby, because painting saved his life. In 1915, reeling from the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, which he had championed and then watched helplessly as it cost some 46,000 men their lives, Churchill had what might appear to be a nervous breakdown. Blamed for unspeakable tragedy, his competency questioned, his name suddenly radioactive, Churchill described feeling like a "sea-beast fished up from the depths, or a diver too suddenly hoisted, my veins threatened to burst from the fall in pressure. I had great anxiety and no means of relieving it; I had vehement convictions and small power to give effect to them." It was in this moment of crisis that his sister-in-law handed him a toy set of oil paints. They had given her children much fun, she said. Maybe they could help him.

Churchill, and indeed Western Civilization, reaped the fruits of this sweet offer. A few years ago, a study conducted by professors at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh and published in the Psychosomatic Medicine Journal, found that people who made time for leisurely activities — defined as "activities that individuals engage in voluntarily when they are free from the demands of work or other responsibilities" — experiences increased life expectancy and life engagement. It improved them physically, mentally and spiritually — as anyone who has pursued a hobby has experienced first hand. The research is even clearer when those hobbies are related to art in some way or another. Studies show that even just looking at art helps produce psychological resilience, but creating it is even better. A 2016 study of 700 adults conducted by Dr. Christina Davies published in the BMC Public Health Journal found that those who recreationally engaged in some form of art (even just two hours per week) experienced significantly better mental well-being.

Churchill was 41 when he took up painting, and he took to it with gusto. He was not particularly talented but even a glance at his pictures reveal how much he enjoyed himself. It's palpable in the brushstrokes. "Just to paint is great fun," he would say. "The colors are lovely to look at and delicious to squeeze out." There are Churchill paintings of The Pyramids and of Jerusalem, a storm over Cannes, some trees in Norfolk, and daybreak at the Riviera — some 500 in all. Early on, Churchill was advised by a well-known painter never to hesitate in front of the canvas (that is to overthink), and he took it to heart. He wasn't intimidated or discouraged by his lack of skill (only this could explain the audacity it took for him to add a mouse to a Peter Paul Rubens painting that hung in one of the prime minister's residences). Painting was about expression of joy for Churchill, it didn't have to be painstakingly planned. It was leisure, not work.

If painting was the cure for his nervous breakdown and depression, this next hobby was about finding something physical and a break from work. In 1924, Churchill was serving as chancellor of the exchequer (a position for which he was in no way qualified considering his tendency toward profligate spending), while having also signed a contract to produce a six-volume, three-thousand-page account of WWI, titled "The World Crisis." Left to his own devices, he might have tried to white-knuckle this impossible workload. But those around him saw the toll that his responsibilities were taking and, worried about burnout, urged him to find another hobby that might offer him a modicum of pleasure and relief. "Do remember what I said about resting from current problems," Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin wrote to him. "A big year will soon begin and much depends on your keeping fit."

So Churchill learned how to lay bricks from two employees at Chartwell, his country estate. Immediately, this dynamo of energy fell in love with the slow, methodical process of mixing mortar, troweling, and stacking bricks. Unlike his other professions—writing and politics—bricklaying didn't wear down his body, it invigorated him. Churchill could lay as many as ninety bricks an hour. As he wrote to the prime minister in 1927, "I have had a delightful month building a cottage and dictating a book: 200 bricks and 2000 words a day." (He also spent several hours a day on his ministerial duties.) A friend observed how good it was for Churchill to get down on the ground and interact with the earth. This was also precious time he spent with his youngest daughter, Sarah, who dutifully carried the bricks for her father as his cute and well-loved apprentice.

"Painting challenged his intellect, appealed to his sense of beauty and proportion, unleashed his creative impulse, and . . . brought him peace," remarked his lifelong friend Violet Bonham Carter. It was also, she said, the only thing Churchill ever did silently. His other daughter, Mary, observed that painting and manual labor "were the sovereign antidotes to the depressive element in his nature." Churchill was happy because he got out of his own head and put his body to work.

For some time now, the party line in career advice has been to "find your passion" and follow it with everything we have. Passion is supposed to be singular. Everything else is a distraction. How can you beat the competition if you've spread yourself out across multiple pursuits? Some of which are only for fun? Isn't your calling supposed to give you everything?

In one of his letters, Seneca — himself a busy political advisor and writer — spoke of how difficult it is for ambitious, career-focused people to take time off to pursue other interests because they are worried about falling behind in their world. The same people who are willing to take great risks to advance their careers will not risk anything for the sake of personal happiness or even mental balance (even if the latter would indirectly help the former). "You must dare something to gain leisure also," he said.

It's not a stretch to say that the 10 years Churchill spent in the political wilderness between 1929 and 1939, painting and reading, laying bricks and feeding the swans and goldfish at Chartwell, was a risky proposition. At many moments, he was ready to charge back into public life--only the counsel of his wife stopped him. But being away from the center of power while appeasement reigned may have been the best thing that ever happened to him, and arguably to the western world. It allowed Churchill to rest, to recharge, and to take the time to actually digest "Mein Kampf." In those pages he saw Hitler for what he truly was, and once he did he was ready.

Randall Stutman has been a coach to some of Wall Street's biggest CEOs for decades. His clients have included Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America. His consulting and advising agency, CRA, has worked with thousands of executives at hundreds of hedge funds and banks. These are people whose entirely livelihood depends on them being perpetually ready to respond to the daily, hourly, sometimes even minute-by-minute volatility of the world's financial markets. Stutman explained to me recently that he often asks these very busy executives how they recharge, given the all-consuming nature of their work. The best, he found, have at least one hobby that gives them peace — things like sailing, long-distance cycling, listening quietly to classical music, scuba diving, riding motorcycles, and fly fishing. There is a surprising commonality between all the hobbies: An absence of voices. For people who make countless high-stakes decisions in the course of a day, a couple hours without chatter, without other people in their ear, where they can simply think (or not think), is essential.

It's interesting to learn that Fred Rogers, the saintly Mr. Rogers, was a bit of a grouch if he didn't get his morning swim in. Or that the NBA champion Chris Bosh taught himself to play guitar and how to code to maintain his sanity in the off season. The writer David Sedaris likes to walk the back roads of his neighborhood in the English countryside and pick up garbage, often for hours at a time. The experimental musician John Cage preferred walking the woods, hunting for mushrooms. Saint Teresa of Ávila loved to dance, and so did Mae Carol Jemison, the first African American woman in space. Obama played basketball and golf while in office, George W. Bush had running, and the diary of William Gladstone, the prime minister a generation before Churchill, shows that during his three terms, from 1880 to the early 1890s, Gladstone went out more than three hundred times to cut down trees with his favorite axe. Tom Cruise, Will Smith, and David Beckham took up fencing together. Peak performance expert and perpetual learner Josh Waitzkin's latest diversion is foil surfing. Tim Ferriss only started a podcast because he was burnout after finishing his third book "The 4-Hour Chef"and wanted to work on his ability to ask questions and steer conversations — two things that, like I've said of all great hobbies, require one to be present.

The swordsman Musashi, whose work was aggressively and violently physical, took up painting late in life, and observed that each form of art enriched each other. Indeed, flower arranging, calligraphy, and poetry have long been popular with Japanese generals and warriors, a wonderful pairing of opposites — strength and gentleness, stillness and aggression.

Nixon was not really capable of taking time off from the job, and surely this contributed to his poor decision making and downfall. Like Trump today, his only relief was his entertainment addiction, watching something like 500 movies while in office. Given the demands of office, zoning out in front of a screen was not sufficiently stimulating or relaxing enough to be restorative. In a time where the average American watches 6 hours of video per day on one device or another, it's worth noting that with few exceptions, watching TV and movies like drinking is not a hobby. It's a vice.

It's in our leisure, Ovid observed, that "we reveal what kind of people we are." What we're seeing right now is that for many people, our leisure is revealing a streak of self-loathing and self-destruction. The American Optometric Association coined the diagnosis "Computer Vision Syndrome" or "Digital Eye Strain," which a study in the Journal of Environmental and Public Health calls "the leading occupational hazard of the 21st century." We spend all day in front of a screen, it's not healthy to relax in front of one too. If that's even possible, given how anxious and worked up and polarized time spent watching the news, scrolling through Twitter or arguing on Facebook seems to make us.

Part of what made painting such a valuable hobby for Churchill was that it taught him how to be present, how to disconnect. To lay down his worries, if only for a minute, and to open his eyes to the beauty of what was around him. A "heightened sense of observation of Nature," he wrote, "is one of the chief delights that have come to me through trying to paint." He had lived for forty years on planet earth consumed by his work and his ambition, but through painting, his perspective and perception grew much sharper. Forced to slow down to set up his easel, to mix his paints, to wait for them to dry, he saw things he would have previously blown right past. After the major powers of WWII met for the Casablanca conference in 1943, weighed down and numb after so much death, Churchill travelled five hours to paint a sunset in Marrakech. He returned to Britain re-energized and ready to finish the task.

In my own life, hobbies have been a salve for and a bulwark against my workaholic tendencies and the grind of a book a year for the last decade. After a breakup in college, I picked up distance running again despite swearing it off after several years of high school track and cross country. Later, I started swimming again--another sport I had been forced into by my parents and long resented. It's ironic that I would spend so much of my adult life willingly engaging in activities I hated as a kid, but today, the first thing I do when I land in a new city is find the best place to go for a long run or a cold swim.

Writing is a mentally exhausting profession. So is running your own business. I get a lot out of both of these things, as do most people who are good at their jobs, but I am also drained by them. Jumping into Barton Springs on a summer morning is almost magically restorative. The way I feel after logging a few miles with headphones on and a song on repeat is enough to make up for a crummy day, a fight with the wife, or a lack of inspiration. I have other hobbies too: Fishing. Hunting. Fixing fences on our farm. It's probably not a coincidence that all my hobbies take me outdoors and outside of my own head.

I am often asked by friends and fans why I don't compete in races or triathlons. My answer is that I'm not trying to "win" my hobby. If I'm being honest, I'm really not even interested in getting much better at them, my goal is mainly to just do more of them. Churchill wasn't trying to make a living from his paintings, he was improving his living through them. It was fun. It was relaxing. The only purpose is the process. It's so easy to forget that.

As difficult as it would have been for me to write my books without my exercise, it's unlikely that Churchill would have managed to work so hard and so long without the hobbies he cultivated. Fred Rogers couldn't have made it through nearly 1,000 episodes of his classic children's television show without swimming and without the piano. It is this clear causal relationship that actually presents a dilemma for the active and the ambitious.

In his famous essay on leisure, the German writer Josef Pieper talked at length about the restorative benefits of leisure, particularly in the busy post-war world that Churchill had helped usher in. It was easy, he said, to think of leisure as something one does to advance their career and to increase our performance, but in the process, deprive it of its meaning. Instead, it must be pursued for the intrinsic benefits. For the peace it brings. For the stillness that settles over us when we do something because we love it, because we're learning, without need for reward or recognition. The rest is extra.

Sitting alone with a canvas? Reading a book for book club? A whole afternoon for cycling? Chopping down trees? Laying bricks. What's the point? Who has the time?

You do. If Churchill did, we all do. And if we don't make the time--to be restore our minds and body, to get a sweat going, to tune or our tune in, to seek out alternately the absence of voices or the delightful sound of them--we risk collapsing under the weight of our obligations and exhaustion.

There's nothing to feel guilty about for being idle. It's not reckless. It's an investment — in you, in your happiness. There is nourishment in pursuits that have no purpose — that is their purpose.

Shares