First, it happened on Fox News. Chris Wallace asked White House adviser Stephen Miller about the president’s decision to use private lawyers “to get information from the Ukrainian government rather than go through … agencies of his government.”

Miller’s response began, “two different points —” when Wallace cut him off.

“How about answering my question?” Wallace asked. Miller, changing the subject, ignored Wallace.

Wallace’s question was never answered.

Then it happened again.

Jake Tapper hosted Congressman Jim Jordan on his CNN program, “State of the Union.” As the interview closed, Jordan simply started ignoring Tapper’s questions and giving his talking points instead. The interview concluded with a visibly frustrated Tapper signaling disappointment about his guest’s avoidance of simple and direct questions.

Both interviews clarified little. These clashes between recalcitrant guests and flustered hosts created sensational television, but rather than enlighten, as journalism should do, the exchanges muddied the story for uninformed viewers.

Audiences critiqued the behavior of the interviewer and interviewees using viral clips on social media, but little was noted about the troublesome aspects of the format itself.

The live TV interview, with its tightly constricted parameters, has much to do with the journalistic failure that occurred.

What happened in these interviews recurs with such regularity that the failure of this exercise is, by now, entirely predictable.

Perhaps it’s time to reconsider the journalistic value of live interviews — and return to a standard that reflects what viewers should expect from news programming.

Live interviews once rare

When radio broadcasting emerged in the 1920s, unscripted live interviews were rare. Radio networks and stations carefully policed their airwaves lest something too disagreeable, spontaneous or controversial caused problems with sponsors or the Federal Communications Commission.

As media history and radio studies scholar Jason Loviglio notes, even popular “vox pop” (people-on-the-street interview) shows were often scripted.

During World War II, broadcast interviews were diligently monitored by the Office of Censorship and the Office of War Information. Scripts of interviews with soldiers and home-front citizens alike were often censored, lest a war secret accidentally slip through.

After the war, radio documentary reporters began asking interviewees critical and even occasionally antagonistic questions in their recordings. But soon the anticommunism infecting American politics made broadcasters wary of unscripted responses. Controversial guests were either blacklisted by the networks or carefully vetted. News interview shows became largely friendly and promotional.

Villains and controversy remained rare even on journalist Edward R. Murrow’s celebrated programs — “See It Now” and “Person to Person.” When they did appear — as in the broadcasts featuring Sen. Joseph McCarthy — they were shown mostly in selectively edited film clips.

Wallace’s revolution

Then Mike Wallace arrived.

Beginning with “Night Beat,” a program aired locally in New York City in 1956 and 1957, Wallace transformed the broadcast interview.

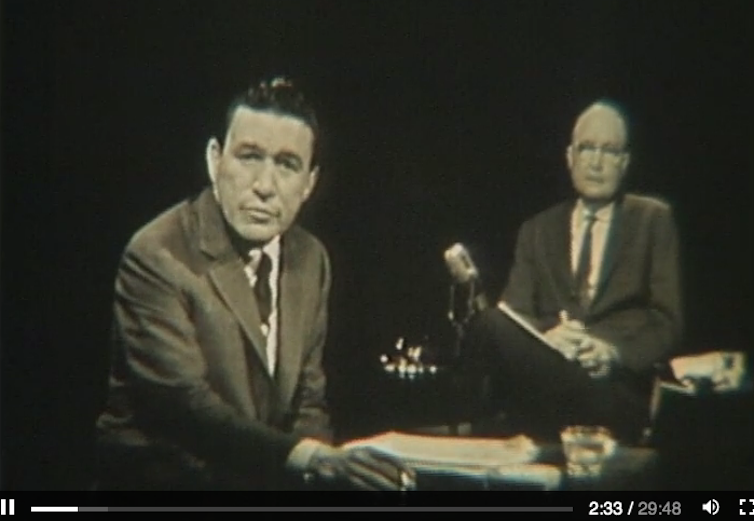

In the documentary “Mike Wallace Is Here,” clips illustrate Wallace’s revolutionary approach. He could be sarcastic, probing, antagonistic and critical. On both “Night Beat,” and “The Mike Wallace Interview,” on ABC, Wallace proved a relentless inquisitor.

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Acting the prosecutor, Wallace watched a procession of gangsters, corrupt politicians and celebrities flinch and dissemble — from segregationist Sen. James Eastland to the controversial author Ayn Rand.

But Wallace’s abrasive style failed to fit the sunny optimism of the Kennedy years. When legal problems and dipping ratings ended his program’s run, the Wallace style wouldn’t return until the late 1960s.

That’s when the credibility gap — caused largely by the government’s misinformation about such stories as the Vietnam War, and the audience’s growing skepticism in an age of assassinations and turmoil — had so widened that critics like The New Yorker’s Michael Arlen argued that television news required more forceful and critical interviewing.

Grilling everyone

In 1968, CBS News assembled a new news magazine — called “60 Minutes” — that forever changed American television.

Although hampered by low ratings in its initial years, Wallace, its star, soon emerged as America’s crusading TV reporter. He’d grill everyone, from the small-time con artist to the president, from dictators to celebrities, to expose their weaknesses and reveal their humanity.

“Imam,” he said to Iran’s revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini during the hostage crisis of 1979, “President Sadat (of Egypt), a devoutly religious man…says that what you are doing now is a disgrace to Islam and he calls you….forgive me, his words, not mine, a ‘lunatic.’”

The ayatollah responded by calling for Sadat’s assassination.

“60 Minutes” spawned numerous imitators. Its mix of sensational investigations, celebrity profiles and engaging stories made it one of the longest-running, and most profitable, network TV shows. It proved just how much money good TV interviews might earn.

“60 Minutes” relied upon carefully produced and edited interviews, but soon satellite technology facilitated live remote interviewing, and the live TV interview format became common. A key evolutionary moment occurred in 1979, when ABC inaugurated a series of shows about the Iran hostage crisis that evolved into “Nightline.”

“Nightline” host Ted Koppel bore in on guests with icy precision. Koppel’s interviews with everyone from the disgraced televangelist Jim Bakker and his wife Tammy Faye to Nelson Mandela became memorable moments in broadcast journalism history.

“Is it going to be possible for you to get through an interview without wrapping yourselves in the Bible?” he asked the Bakkers.

Other TV interviewers, including Barbara Walters and Larry King, developed their own idiosyncratic styles in both live and taped programs. Audiences loved their favorite interviewers, and the TV interview reliably delivered high ratings and lucrative ad revenue.

But nothing equaled “60 Minutes.” At its ratings apex, the program’s most attractive feature remained those Mike Wallace interviews. On Sunday nights, after NFL football, Mike Wallace’s weekly inquisition became an American TV ritual.

Stonewalling inevitable

The legacy of “60 Minutes” is mixed. Many young reporters idolized Wallace, and soon every TV market in America had its investigative I-teams revealing local swindles. Antagonistic interviews with bad guys became routine.

By the 1980s, talk shows with hosts like Morton Downey Jr. began inviting guests to appear in order to belittle them. Downey generated high ratings by yelling “Shut up!” at everyone in the studio.

Later, at Fox News, Bill O’Reilly’s hectoring and insults also produced high ratings.

Encouraged, TV news interviewers yelled more. Guests soon realized this, and began preparing more carefully by strategically rehearsing talking points and planning to ignore questions in favor of repeating their own messages.

The Tapper and Wallace interviews represent the culmination of this trajectory. It was entirely predictable that their guests would stonewall any semblance of dialogue.

Journalism’s obligation

The cable channels have nobody to blame but themselves. They have boxed themselves in with the popularity of their live interview shows and found success with a format that is both constricting and ripe for exploitation.

“60 Minutes” very rarely aired live interviews because that program’s producers knew live TV can be commandeered.

On a live broadcast, when a guest misbehaves or misinforms the audience, a host has few options. They can ungraciously argue and yell, but that might inspire sympathy for the interviewee. They can cut off the microphone, but that might incite charges of censorship.

There’s one option that could be considered by these programs: not inviting guests who will mislead audiences with provably inaccurate information.

The Biden campaign recently asked that Rudy Giuliani, the president’s personal lawyer, be excluded from interviews for these journalistic reasons. The request argues that the balance between informing and misinforming viewers is a journalistic question, not a political one.

Ultimately, this is not an ethical issue of “balance” or fairness. Citizens require credible, verified and accurate information to perform their democratic responsibilities.

There’s no journalistic obligation to disseminate views that mislead, misdirect or offer irrelevant information designed to intentionally confuse viewers. In fact, there is a journalistic obligation to do the opposite. To fulfill their democratic and journalistic responsibilities, perhaps TV news operations airing these programs could consider inviting alternative guests and changing the standard format.

That way, we could all be more reliably informed.

Michael J. Socolow, Associate Professor, Communication and Journalism, University of Maine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative

Shares